An international team led by the University of Oxford has identified one of the most massive and unusual structures in the Universe, a giant cosmic filament located 140 million light-years away. This structure, composed of a “razor-thin” string of galaxies, is rotating in a way that challenges existing theories about galaxy formation. The study, published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, provides a new perspective on how galaxies acquire their spin and evolve, shedding light on the forces shaping the Universe’s largest structures. Data from advanced telescopes like South Africa’s MeerKAT played a key role in uncovering these remarkable findings.

A Dual Motion Like Never Before

What makes this new cosmic structure truly exceptional is not only its size but the way it exhibits both spin alignment and rotational motion. According to Co-lead author Dr. Lyla Jung from the University of Oxford,

“What makes this structure exceptional is not just its size, but the combination of spin alignment and rotational motion. You can liken it to the teacups ride at a theme park. Each galaxy is like a spinning teacup, but the whole platform—the cosmic filament—is rotating too.”

This fascinating dual motion offers rare insights into how galaxies gain their spin from the larger structures in which they reside. It’s a phenomenon that could deepen our understanding of how galactic rotation evolves over time and across vast distances.

The galaxies observed within this filament are aligned in such a way that their spins are not random but are largely in the same direction, mirroring the overall rotation of the filament itself. This alignment challenges traditional models of galaxy formation and offers a new framework for exploring the forces at work in these colossal cosmic structures. It’s as though the very fabric of the Universe is imparting its angular momentum to the galaxies it hosts.

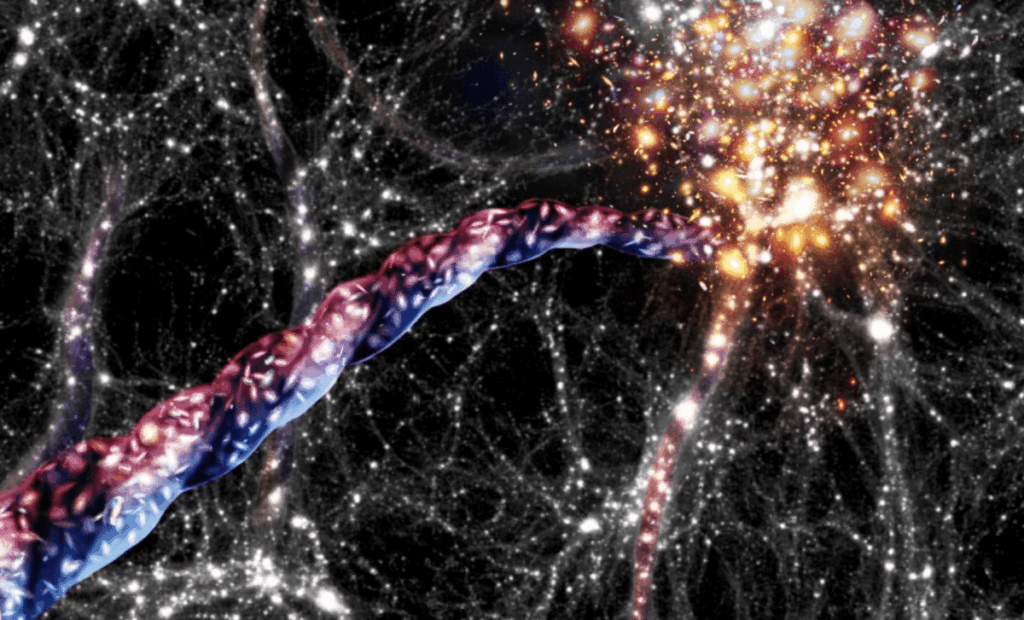

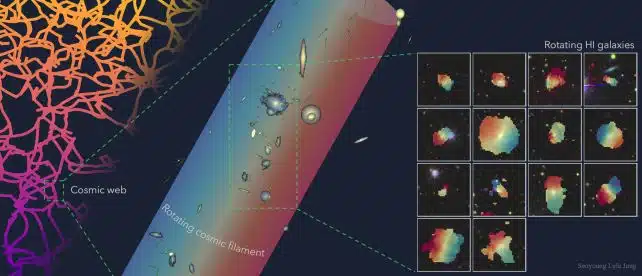

A diagram illustrating the filament. (Lyla Jung)

A diagram illustrating the filament. (Lyla Jung)

The Role of Cosmic Filaments in Galaxy Evolution

Cosmic filaments are among the largest known structures in the Universe, stretching across millions of light-years. These vast threads of galaxies and dark matter form the backbone of the cosmic web, serving as highways along which galaxies and other matter flow. The discovery of this spinning filament adds an important chapter to the story of galaxy formation, offering a unique look into the interplay between large-scale cosmic structures and the evolution of galaxies.

Co-lead author Dr. Madalina Tudorache, from both the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge and the Department of Physics at Oxford, emphasized the significance of this filament in understanding the Universe’s history.

“This filament is a fossil record of cosmic flows. It helps us piece together how galaxies acquire their spin and grow over time,” Dr. Tudorache said.

By studying the gas-rich galaxies embedded within this filament, researchers can trace the flow of matter and momentum through the cosmic web, shedding light on the processes that govern galaxy evolution, star formation, and the overall development of the Universe.

The gas content of these galaxies is crucial for understanding star formation, as hydrogen is the raw material for new stars. By focusing on these hydrogen-rich galaxies, scientists can study how cosmic gas funnels through filaments and into galaxies, providing a clearer picture of how angular momentum and other factors influence galaxy morphology and spin. This also offers clues about how galaxies form and evolve in the early Universe, a period still shrouded in mystery.

The Technology Behind the Discovery

This extraordinary discovery would not have been possible without the powerful tools and technologies available to astronomers today. The research team utilized data from South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope, one of the world’s most advanced observatories. The telescope’s 64 interlinked satellite dishes allowed the team to conduct a deep sky survey known as MIGHTEE, which revealed this giant rotating cosmic filament. Complementary optical data from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) helped complete the picture, revealing not just the filament’s structure but also its rotational motion.

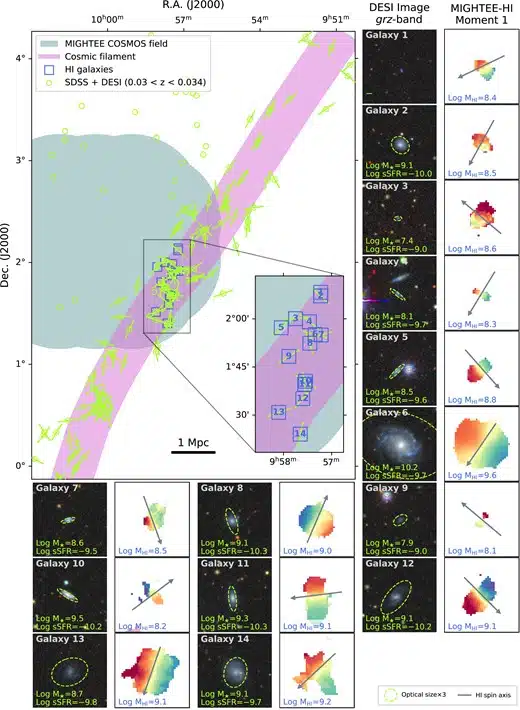

Top left: the on-sky distribution of H i galaxies (squares), SDSS and DESI optical galaxies (circles and lines, depending on the availability of optical PA measurements), and the cosmic filament. The MIGHTEE COSMOS footprint is shown in a block. Other panels show the DESI multiband cutout image and the H i moment-1 map of each H i-selected galaxy. The size of the images and moment maps is fixed to 80 arcsec across each panel. The dashed ellipse in each DESI image panel shows the ellipticity and the size (tripled for visual purposes) of the optical counterpart of each H i galaxy. Note that Galaxy 1 does not have an optical DESI counterpart. The arrow in the moment-1 map is the H i spin axis.

Top left: the on-sky distribution of H i galaxies (squares), SDSS and DESI optical galaxies (circles and lines, depending on the availability of optical PA measurements), and the cosmic filament. The MIGHTEE COSMOS footprint is shown in a block. Other panels show the DESI multiband cutout image and the H i moment-1 map of each H i-selected galaxy. The size of the images and moment maps is fixed to 80 arcsec across each panel. The dashed ellipse in each DESI image panel shows the ellipticity and the size (tripled for visual purposes) of the optical counterpart of each H i galaxy. Note that Galaxy 1 does not have an optical DESI counterpart. The arrow in the moment-1 map is the H i spin axis.

Credit: Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Professor Matt Jarvis, a key figure in the study published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, pointed out how essential the combination of different observatories was for this discovery:

“This really demonstrates the power of combining data from different observatories to obtain greater insights into how large structures and galaxies form in the Universe. Such studies can only be achieved by large groups with diverse skillsets, and in this case, it was really made possible by winning an ERC Advanced Grant/UKIR Frontiers Research Grant, which funded the co-lead authors.”

This synergy between various research institutions and state-of-the-art technology underscores the importance of collaboration in modern scientific research.