The arrival of 3I/ATLAS in our Solar System spawned multiple proposals for a rendezvous mission to study it up close. As the third interstellar object (ISO) ever detected, the wealth of information direct studies could provide would be groundbreaking in many respects. However, the mission architecture for intercepting an interstellar comet poses numerous significant challenges for mission designers and planners. Chief among them is the technological readiness level (TRL) of the proposed propulsion systems, ranging from conventional rockets to directed-energy propulsion (DEP).

So far, mission proposals have focused on chemical rockets launched from Earth, like NASA’s Janus mission and the ESA’s Comet Interceptor, or on existing missions like the Juno probe adjusting their trajectories to rendezvous with it. In a recent paper, researchers from the Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is) propose foregoing a direct transfer mission that would launch from Earth today. Instead, they demonstrate how a mission launching in 2035 could intercept 3I/ATLAS using an indirect Solar Oberth maneuver.

Adam Hibberd, a software and research engineer in Astronautics with the i4is and the owner/director of Hibberd Astronautics Ltd., led the study. He was joined by T. Marshall Eubanks, the Chief Scientist at Space Initiatives Inc. and the CEO of Asteroid Initiatives LLC., and Andreas Hein, an Associate Professor of Aerospace Engineering at the University of Luxembourg and the Chief Scientist at the Interdisciplinary Centre for Security, Reliability and Trust. Their paper has accepted for publication in the Journal of the British Interplanetary Society (JBIS).

The main challenges for a direct mission to rendezvous with 3I/ATLAS stem from the target object’s celestial mechanics, its high heliocentric speed, and the late initial detection. The first issue effectively rules out a rendezvous mission that relies on an onboard propulsion system to match the comet’s velocity, thereby enabling a prolonged close-up study of the body. As a result, a flyby mission is the preferred option. However, the second and third considerations rule out a direct mission because the optimal launch date had already passed before it was detected. As Hibberd summarized these for Universe Today via email:

For the direct mission, the object 3I/ATLAS was detected too late, when it had already travelled inside the orbit of Jupiter, and with a velocity in excess of 60 km/s. It turns out, this was after the optimal launch date for a direct mission to intercept it. One paper found that there would even have been difficulties for a ‘Comet Interceptor’ spacecraft had it been already loitering at the Sun/Earth L2 point when 3I/ATLAS was discovered.

This is where Hibberd employed the Optimum Interplanetary Trajectory Software (OITS), which he designed, to assess the feasibility of direct and indirect missions to intercept ISOs. This software has a proven track record for solving missions with Solar Oberths, which includes a previous i4is study for a mission (Project Lyra) that would intercept the first ISO ever detected, ‘Oumuamua. Integral to Project Lyra and other missions utilizes OTIS is the use of gravitational assists (GAs) and/or Oberth Maneuvers.

The former involves a slingshot maneuver that leverages a planet’s (or moon’s) gravity to increase speed. The latter consists of a spacecraft under the gravitational influence of a massive body (the Sun), waiting to reach its closest pass (perihelion), then applying thrust to achieve a high heliocentric speed. The spacecraft can either achieve escape velocity from the Solar System this way, or pick up enough speed to rendezvous with an ISO that has already traveled a huge distance by this time. Said Hibberd:

The Solar Oberth option is designed for when an interstellar object has passed through its perihelion (closest approach to the Sun) and is receding rapidly away from the Sun. It recognizes the fact that a humongous speed needs to be generated by a spacecraft to catch such an object and exploits the so-called ‘Oberth Effect’ in order to generate this speed. When a spacecraft approaches the Sun, the Sun’s gravitational attraction increases its velocity until the perihelion is reached, then the spacecraft burns its solid-propellant engines at this optimal point, to maximize the ‘slingshot effect’, and to accelerate the probe expeditiously to the target object, in this case 3I/ATLAS.

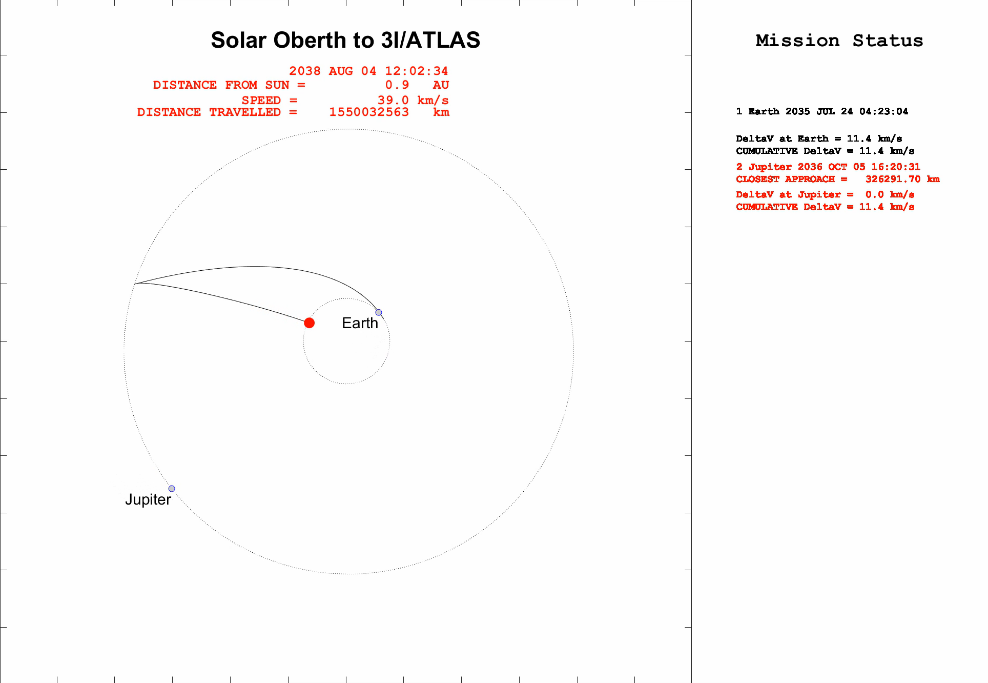

*OTIS simulation of a spacecraft intercepting 3I/ATLAS using a Solar Oberth maneuver. Credit: Hibberd, et al. (2026)/i4is*

*OTIS simulation of a spacecraft intercepting 3I/ATLAS using a Solar Oberth maneuver. Credit: Hibberd, et al. (2026)/i4is*

Based on their OTIS simulations, the team found that an intercept could be achieved via a Solar Oberth maneuver, but the launch would have to occur in 2035 to achieve optimal alignment between Earth, Jupiter and 3I/ATLAS. The flight duration would be 50 years (though Hibberd notes that this could be reduced marginally). “2035 is optimal because the alignments of the celestial bodies involved (i.e. the Earth, Jupiter, Sun, and 3I/ATLAS) are the most propitious to reach 3I/ATLAS with a minimum Solar Oberth propulsion requirement from the probe, a minimum performance requirement for the launch vehicle, and a minimum flight time to the target,” he said.

While such a mission would take a long time to intercept an ISO, the scientific returns would be nothing short of revolutionary. Asteroids and comets are essentially material leftover from the formation of planetary systems. As such, the study of ISOs would reveal things about other star systems without having to send missions to them, which could take centuries or longer. While DEP is being investigated as a possible solution, a la Swarming Proxima Centauri (another i4is project), the TRL of this concept is likely many decades away.

In the meantime, a spacecraft developed with current technology that relies on a Solar Oberth maneuver could reach an ISO and provide a detailed analysis in the same time frame. Even if we never send missions to nearby stars to observe what is there, an ISO interceptor could tell us all we need to know about systems beyond ours.

Further Reading: arXiv.org