Astronomers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) have announced the first-ever detection of hydrogen sulfide around a system of four distant gas giant planets outside our own solar system.

The NASA-funded team behind the historic detection said their work confirms that the previously detected objects are planets and not brown dwarfs. The discovery also helps solve a longstanding question about how these types of gas giant planets form.

While the four planets are not in the star’s habitable zone, the team suggests that the technique used to separate the planets’ dim light from their bright host star will also aid the search for life on other planets.

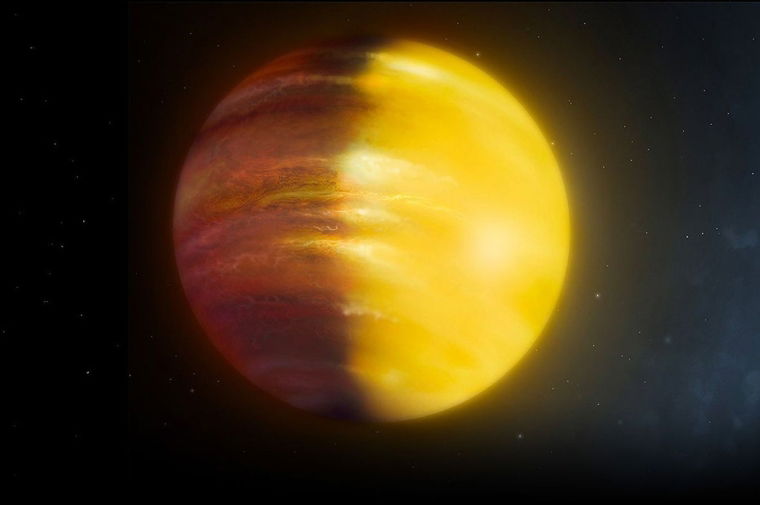

The James Webb Space Telescope Spots Sulfur in a Giant Four-Planet System

According to a statement, the team made the discovery while analyzing spectral data previously captured by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) on a distant star called HR 8799. Due to the sensitivity of JWST’s instruments, astronomers can differentiate the spectral “signature” of different molecules even at these astronomical distances.

Located approximately 133 light-years from Earth, the star hosts four gas giants that are in the same general planetary category as the local gas giants Jupiter and Saturn, although they are much larger. For example, the smallest is 5 times as massive as Jupiter, while the largest is 10 times as massive. The four gas giants also have highly eccentric orbits, with the closest planet roughly 15 times farther from its host than Earth is from the Sun.

“For a long time, it was kind of unclear whether these objects are actually planets or brown dwarfs,” said UCLA postdoctoral researcher and study co-author Jerry Xuan.

Because the planets are about 10,000 times fainter than their host star, UCSD research scientist and study co-author Jean-Baptiste Ruffio had to develop new data analysis techniques to separate their spectral signatures from the star’s light. Next, Xuan created detailed atmospheric models of the planets based on JWST data.

When the team compared the two, they found sulfur in the form of hydrogen sulfide. However, when the team examined the sulfur-to-hydrogen ratio and separately compared the carbon-to-hydrogen and oxygen-to-hydrogen ratios, they found something unexpected. Instead of the same ratios found in the star, the planetary ratios were much higher.

According to the researchers, this ‘uniform enrichment’ indicated that the composition of the planets “has to be quite different from that of the star.” They also noted that scientists already have difficulty explaining the uniform enrichment of carbon, oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen on Jupiter.

“But the fact that we’re seeing this in a different system is suggesting that there’s something universal going on in the formation of planets,” Xuan said, before adding that “it’s quite natural to have them accrete all heavy elements in nearly equal proportions.”

How the Detection Affects Planet Formation and the Search for Life

When discussing the implications of their discovery, the research team noted that finding sulfur around objects this massive helps solve the mystery of how gas giant planets form. That’s because gas giants like Jupiter and Saturn are mostly composed of hydrogen and/or helium around a dense core, much like a nascent star.

Until now, scientists thought that if such a planet were larger than 13 times Jupiter’s mass, the added mass would ignite deuterium fusion, resulting in an object called a brown dwarf, which lies on the boundary between a planet and a star.

“The boundary between star formation and planet formation is quite fuzzy at these middle mass ranges,” said Xuan. “The definition that says a brown dwarf is an object more massive than 13 Jupiter masses is fairly arbitrary. It’s not based on knowledge of how planets and stars form.”

“I think the question is, how big can a planet be?” Ruffio added. “Can a planet be 15, 20, 30 times the mass of Jupiter and still have formed like a planet? Where is the transition between planet formation and brown dwarf formation?”

Although the four planets’ orbits outside their star’s habitable zone and gas giants are considered unlikely candidates for life, Xuan said their work will aid the search for Earth-like exoplanets that may host extraterrestrial life. That’s because the team’s approach, which allowed them to ‘visually and spectrally’ separate the light from the planets from the host star’s light, “will be useful for studying exoplanets at great distances from Earth in clear detail.”

“Finding an Earth analog is the holy grail for exoplanet search, but we’re probably decades away from achieving that,” said Xuan. “But maybe in 20-30 years, we’ll get the first spectrum of an Earth-like planet and search for biosignatures like oxygen and ozone in its atmosphere.”

The study “Jupiter-like uniform metal enrichment in a system of multiple giant exoplanets” was published in Nature Astronomy.

Christopher Plain is a Science Fiction and Fantasy novelist and Head Science Writer at The Debrief. Follow and connect with him on X, learn about his books at plainfiction.com, or email him directly at christopher@thedebrief.org.