It’s well established that the universe is expanding, but there’s serious disagreement among scientists over how fast it’s happening.

Two of our best ways of measuring the cosmic expansion rate, the Hubble constant, give answers that are stubbornly at odds. This presents a major problem in modern cosmology known as the Hubble tension.

However, we wondered if an idea originally proposed to solve another cosmic mystery — the origin of cosmic magnetic fields — could help us unlock the mystery of the Hubble tension.

Our recently published research explores whether extremely weak magnetic fields left over from the earliest moments after the Big Bang might help us unpack the Hubble tension, while offering a glimpse into physics at energies far beyond anything achievable on Earth.

Read more:

The universe may be lopsided – new research

The Hubble constant and tension

Astronomers use the Hubble constant as a measure of how fast the universe is expanding. It is named after the American astronomer Edwin Hubble who first discovered that the universe is expanding.

An explainer on the Hubble constant and Hubble tension. (University of Chicago)

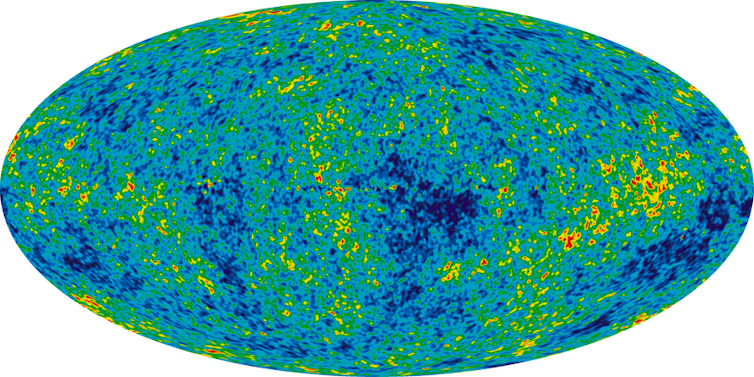

There are two conceptually different approaches to measuring the Hubble constant. One is indirect, based on predictions of our cosmological model tuned to match the patterns in the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang.

Telescopes such as the Planck Space Telescope have measured tiny fluctuations in this ancient light, predicting a Hubble constant of about 67 kilometres per second per megaparsec (km/s/Mpc). A parsec is a unit of distance used in astronomy equal to about 3.26 light years, or 30.9 trillion kilometres. A megaparsec is one million parsecs.

The second method is more direct, similar to the one used by Hubble in the 1920s when he first demonstrated that the universe is expanding.

It measures how fast distant galaxies are moving away from our home galaxy, the Milky Way, by observing the brightness of supernovae explosions in these far away galaxies.

Type Ia supernovae are known to be “standard candles” because we know that their luminosity is the same wherever they are. That means we can judge the distance to them from how dim they appear to us.

Read more:

How fast is the Universe really expanding? Multiple views of an exploding star raise new questions

To determine their intrinsic brightness, astronomers use other standard candles, such as Cepheid stars, in the galaxies nearby. These observations, which use the Hubble and James Webb space telescopes, give a higher value of around 73 km/s/Mpc.

This difference between the two measurements is called the Hubble tension. The difference between 67 and 73 may seem small, but it is statistically highly significant. If both methods are correct, then our standard model of cosmology must be missing something important.

An explainer on how astronomers measure cosmic distances. (NASA)

Where did cosmic magnetic fields come from?

Magnetic fields are everywhere in the universe. Planets and stars generate their own fields, but gaps in our understanding emerge when we attempt to explain the much larger scale magnetic fields threading galaxies and clusters, and possibly even cosmic voids.

One long-studied possibility is that magnetism first arose in the very early universe, long before the first stars or galaxies formed. These so-called primordial magnetic fields have been studied for decades, and searching for their imprints in the cosmic microwave background and other data offers a way to probe the early universe and the extreme energies that would have generated these fields.

In 2011, two of us (Karsten and Tom) pointed out that primordial magnetic fields would influence recombination — when electrons and protons first combined to form neutral hydrogen — and the universe turned from opaque to transparent. The first light able to travel freely from that moment on is what we now observe as the cosmic microwave background.

If present, primordial magnetic fields would speed up recombination by pushing and pulling on charged particles, making matter slightly clumpy. Where particles are more crowded, they are more likely to meet and form hydrogen.

Shifting the moment when the universe becomes transparent changes the size of the observed patterns in the cosmic microwave background. This effectively alters the cosmic ruler used to measure distances and, in turn, the value of the Hubble constant inferred from the model, helping to ease the Hubble tension. Two of us (Karsten and Levon) demonstrated this effect in 2020 using a simplified model of recombination.

A breakthrough: What we found

A map created by NASA’s Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe of the microwave radiation released approximately 375,000 years after the birth of the universe.

(NASA/WMAP Science Team)

In our new paper, we used the first full three-dimensional simulations of the primordial plasma with magnetic fields embedded in it, tracking how hydrogen forms.

We used the hydrogen formation history found through these simulations to compute predictions for how cosmic microwave background should appear if there were primordial magnetic fields, and tested these predictions against observations of the background.

The cosmic microwave background is extraordinarily sensitive to changes in recombination. If primordial magnetic fields altered it in a way that disagreed with observations, the idea could be ruled out. Instead, the data showed that our proposal remains viable.

Across multiple combinations of datasets, we find a consistent, mild preference for primordial magnetic fields, ranging from about 1.5 to three standard deviations. This is not yet a discovery, but a meaningful hint that they exist.

Equally important, the field strengths favoured by the data, about five to 10 pico-Gauss today, are close to what would be needed for galaxy and cluster magnetic fields to originate from primordial seeds alone. A pico-Gauss is a unit used to measure the strength of magnetic fields.

Aside from helping ease the Hubble tension, if primordial magnetic fields are confirmed, they would open a new window into how the universe was when it was only split seconds old, perhaps offering a glimpse into important events such as the Big Bang itself.

Our results show that the proposal survives the most detailed test available today and provides clear targets for future observations. Over the next several years, we will learn whether tiny magnetic fields from the dawn of time helped shape the universe we see today and whether they hold the key to resolving the Hubble tension.