In a breakthrough, Israeli researchers have measured invisible particles known as cosmic rays deep inside a dust cloud 400 light-years from Earth.

The peer-reviewed study detecting these previously unobserved particles could help shed light on how stars are born in the galaxy.

“These cosmic rays are crucial for our understanding of the process of formation of new stars,” lead researcher Prof. Shmuel Bialy of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology’s Physics Faculty told The Times of Israel. “This just opened the door for a whole new field of research in modern astrophysics.”

Bialy’s international team used observations from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to measure infrared radiation from cosmic rays that had penetrated the gigantic nebula Barnard 68 in the faraway constellation Ophiuchus.

The research was published in Nature Astronomy on Wednesday.

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

“Nobody thought it would be possible to observe these cosmic rays because they were never seen before,” said Bialy. “Now, we show that it’s possible. We were the first to observe it, and the signal was strong and clear.”

Dr. Shmuel Bialy of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Physics, left, and Amit Chemke, a master’s degree student in Bialy’s group. (Courtesy)

Cosmic rays: ‘high-energy particles’

“It is important to people on Earth because we’re researching how stars are formed,” said Amit Chemke, 27, a master’s student in Bialy’s group and co-author of the research paper. “Our Sun was formed billions of years ago, but how are other suns forming?”

Speaking to The Times of Israel, Chemke said that the term “cosmic rays” is “confusing” because the rays are not radiation or connected to light.

They were discovered and then named by Victor F. Hess in 1912, and the name stuck.

“They are actually particles of matter — protons, electrons, and atomic nuclei,” Chemke said. “These high-energy particles are buzzing around the galaxy” almost at the speed of light.

“They are very energetic, and they bump into dust clouds, or nebulae,” he said.

Gigantic dust and space clouds in between the stars

A nebula is an enormous cloud that exists in the space between stars. The galaxy is filled with these massive clouds, which contain dust and gases, including hydrogen and helium.

“The Sun is like a grain of salt compared to these clouds,” said Bialy.

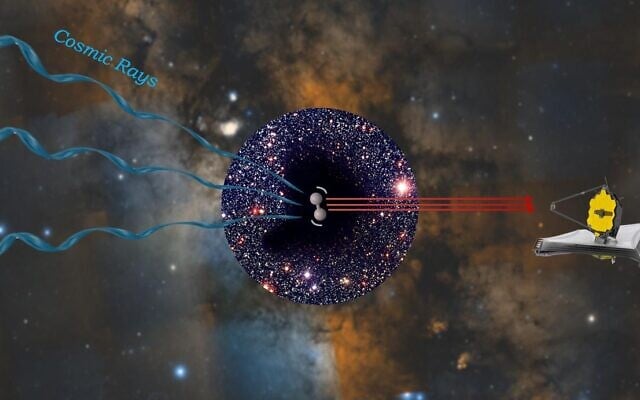

Illustration of the key process in which cosmic rays enter the nebula and lead to the excitation of molecular hydrogen, making it vibrate. This results in the emission of infrared radiation, which NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope detects. (Courtesy/Dr. Shmuel Bialy)

Some nebulae are created from the gas and dust emitted from the explosions of dying stars. Others are regions where new stars are starting to form.

When the flying particles of these cosmic rays hit a nebula, they can “penetrate all the way through,” Chemke explained.

The particles cause hydrogen molecules inside the nebula to vibrate. This vibration emits infrared radiation, which the researchers were then able to measure.

Trifid Nebula, photographed by David ‘Deddy’ Dayag (Courtesy/David Dayag)

Inside the nebula, the cosmic rays spark chemical processes, including the creation of new molecules such as water, ammonia, and methanol.

“The cosmic rays have an effect on the star formation process,” Chemke said.

‘We said, let’s try it. Why not?’

People have been observing infrared radiation coming from massive, hot stars for decades, said Bialy. “These hot stars emit intense UV radiation in places like the Orion Nebula, for example.”

However, cosmic rays from nebulae are much fainter, he said, and scientists said they weren’t strong enough to be observed.

Cone nebula, photographed by David ‘Deddy’ Dayag (Courtesy/David Dayag)

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Bialy said, he kept working on a decades-long theory about radiation emitted from cosmic rays in nebulae.

“I just kept on going because I enjoyed the process of doing the equations, calculating everything,” he said. “I thought that even if we never observe it, I’m having fun.”

Bialy said that even as a child, he always loved physics and astronomy.

He grew up in Russia before his family immigrated to Israel. His parents told him that he spoke his first sentence in Russian one night when he exclaimed, “Look, look, a star!”

During his post-doctorate at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Bialy befriended Italian astronomer Sirio Belli, whose specialty was observing infrared radiation.

Bialy shared his calculations. “We said, let’s try it. Even if people say we can never observe it, why not?” he said.

The two set up a telescope at an observatory in Arizona, observing nebulae for “20 hours of very long exposure. And guess what? We didn’t see anything.”

The Seagull nebula, seen in this infrared mosaic from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer. (NASA/Flash90)

The pair of scientists then decided to ask if they could conduct research using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, which is a “much more sensitive instrument than anything we have on Earth.”

The telescope, launched in December 2021, orbits the Sun about 1.5 million kilometers (930,000 miles) away from the Earth.

Bialy said that for every 10 proposals that NASA receives for the telescope, only one gets chosen.

“After a few trials, we were approved,” Bialy said. “We got eight hours of research time on the James Webb Space Telescope.”

In this image provided by NASA, the James Webb Space Telescope is released into space from an Ariane rocket on Saturday, December 25, 2021. The telescope is designed to peer back so far that scientists will get a glimpse of the dawn of the universe about 13.7 billion years ago and zoom in on closer cosmic objects, even our own solar system, with sharper focus. (NASA/AP File)

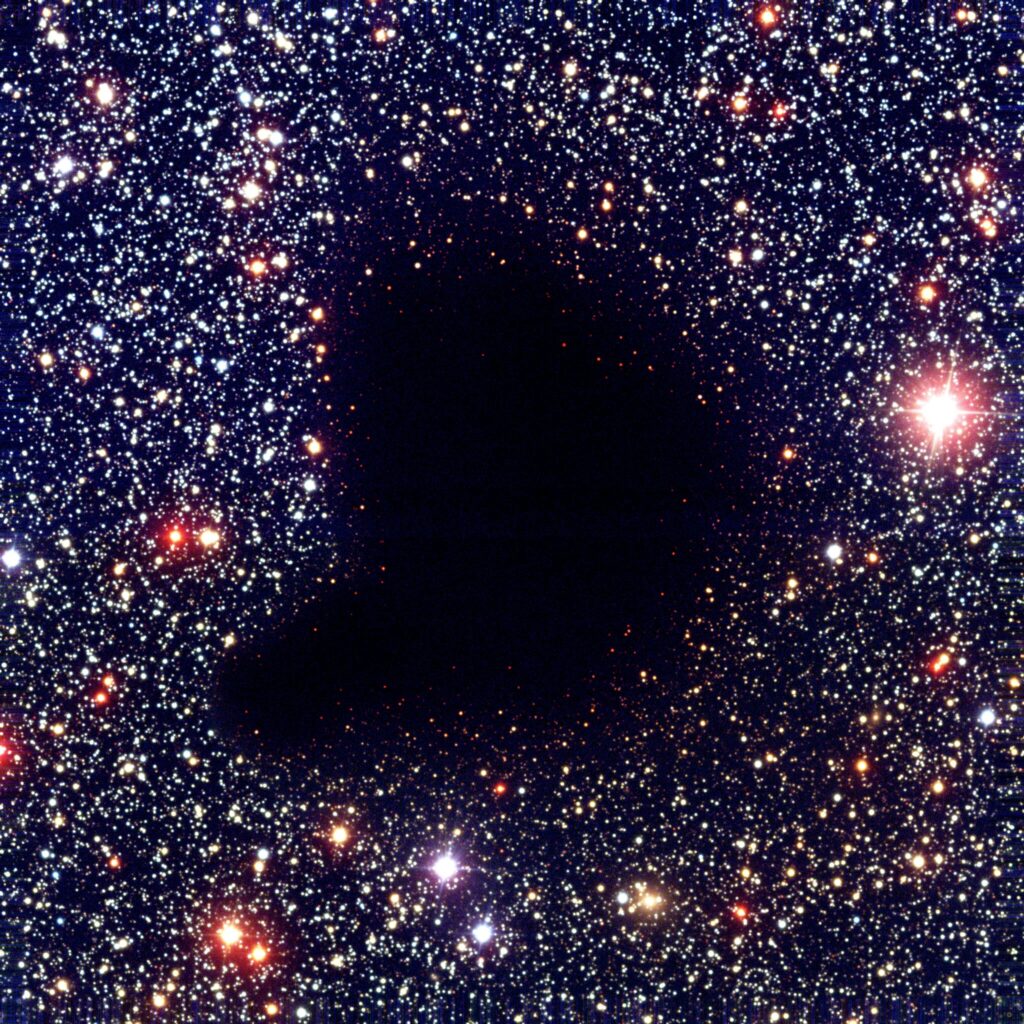

The Barnard 68 nebula, about 2 million times larger than the Sun, is cold and dense, with temperatures of around 10-20 Kelvin, barely above absolute zero. According to predictions, it will collapse in about 200,000 years, forming a new star.

But until that happens, the researchers were able to detect the infrared radiation emitted from the vibrating hydrogen molecules inside the nebula.

David Neufeld, professor of physics and astronomy at Johns Hopkins University, who was also part of this study, said the data from NASA’s telescope “has opened a completely new window on cosmic-ray astrophysics.”

The research team has now received another 50 hours of observational data from space to analyze.

“This will enable us to effectively measure the intensity of cosmic rays in many places in the galaxy,” Bialy said. “And ultimately, in the years to come, we plan to extend it even further, maybe to many tens of nebulae around us to measure the distribution of cosmic rays throughout galactic space.”