Each time we’ve looked at the Universe in a fundamentally new way, we didn’t just see more of what we already knew what was out there. In addition, those novel capabilities allowed the Universe to surprise us, breaking records, revolutionizing our view of what was out there, and teaching us information that we never could have learned without collecting that key data. It’s happened many times before, including:

with the invention of the telescope,

with the development of astrophotography (astronomical photography),

with the birth of multiwavelength astronomy,

with the advent of space telescopes,

with the technique of deep-field imaging,

and with the improvements of larger-aperture, longer-wavelength observatories.

We gained, in each instance, a better appreciation for what the Universe was made of as well as what it looked like, and a greater understanding of what objects were present within it, in what numbers, and where they could be found. Here in the 21st century, the Hubble Space Telescope — the flagship telescope of the 20th century — now finds itself alongside an array of brilliant space telescopes: JWST, Euclid, SPHEREx, with the Nancy Grace Roman Telescope expected to join them later this year. As the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) now approaches its fifth year of science operations, the time has come to use its capabilities to do one of the most extraordinary things one can do with it: take the deepest deep-field image ever possible in human history.

Here’s how we got to this point, and why now is absolutely the right time for this bold, record-breaking initiative to move forward.

Behind the dome of a series of European Southern Observatory telescopes, the Milky Way towers in the southern skies, flanked by the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, at right. Although there are several thousand stars and the plane of the Milky Way all visible to human eyes, there are only four galaxies beyond our own that the typical unaided human eye can detect. We did not know they were located outside of the Milky Way until the 1920s: after Einstein’s general relativity had already superseded Newtonian gravity. Today, this view helps us appreciate the awe and wonder that the Universe, and the cosmic story, holds for each of us.

Credit: ESO/Z. Bardon (www.bardon.cz)/ProjectSoft (www.projectsoft.cz)

If you want to know what the Universe looks like, you have to observe it in a way that will reveal its finest details. It’s easy to see objects that are bright and nearby, sure; most of those you can see with simple equipment and just your eye. To see what the Universe truly looks like, however, you need to be sensitive not just to those “easy” objects, but the hard ones as well. That means that it’s important to reveal objects that are also:

range from bright-to-faint,

have intrinsic colors that range from blue-to-red,

range from being dusty to being dust free,

and objects that exist at all distances, from nearby to intermediate to extremely far away.

For the brightest, bluest, most dust-free, and most nearby objects, we can see them with either our naked eye or a simple, often modest, ground-based telescope. However, only a small fraction of the Universe is all of those things: bright, blue, dust-poor, and nearby. Most of the galaxies in the Universe are small and faint; most of the stars in the Universe emit primarily red or even infrared light; most of the galaxies in the Universe are rich in dust; most of the Universe that’s observable to us are located at significant cosmic distances.

There are several things that we can do to help reveal those more obscure objects, and it’s by doing those things all together — which we’ll ultimately get to — that will finally reveal the deepest views of the Universe ever acquired.

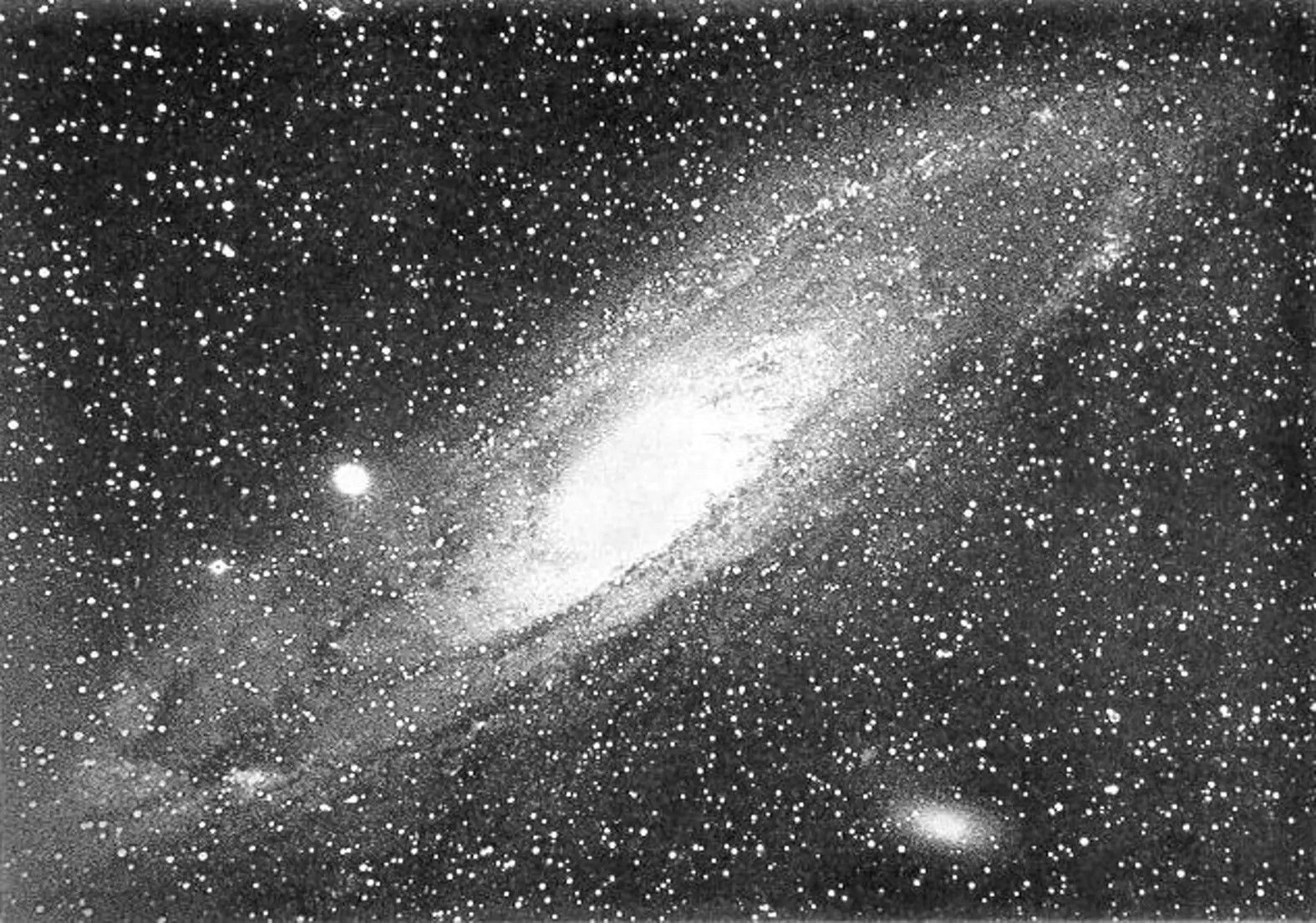

This 1888 image of the Andromeda Galaxy, by Isaac Roberts, is the first astronomical photograph ever taken of another galaxy. It was taken without any photometric filters, and hence all the light of different wavelengths is summed together. Every star that’s part of the Andromeda galaxy has not moved by a perceptible amount since 1888, a remarkable demonstration of how far away other galaxies truly are. Although Andromeda is a naked-eye object under even modestly dark skies, it was not recorded until the year 964, and was not shown to be extragalactic until 1923.

Credit: Isaac Roberts

The obvious first step is to gather as much light as possible. This can occur in two ways.

You can build large-aperture telescopes. Astronomers often refer to telescopes as “light buckets,” because you literally use them to collect photons. The bigger your bucket, the more light it can collect, and hence, the fainter the objects are that you can reveal. Building larger telescopes also has the advantage of increasing your resolution. The resolution of a telescope (or any instrument, including your eye) is dependent on how many wavelengths of light fit across the diameter of your telescope (or eye), and so the larger your telescope is, the better its resolution is. (And telescopes that are sensitive to longer wavelengths require larger apertures to reach the same resolution.)

You can also increase your exposure time. Prior to the 1800s, the human eye was the only tool we have for “viewing” things. You could paint, sketch, or otherwise draw what you observed, and you could enhance what you were capable of seeing with systems of mirrors and lenses, but that was kind of the limit. All of that changed when photography was developed in the 19th century, and then was applied to astronomy later in that century. Today, we can observe light across many different wavelengths and many different long-exposure images, stack them all together, and produce deep, full-color photographs.

These steps have led to us seeing not merely our world, but also, by extension, objects well beyond our world, in greater detail than would have been possible without gathering sufficient amounts of light across multiple wavelengths.

This photograph, from 1911, demonstrates the technique of additive color mixing as applied to photography. Three color filters, blue, yellow, and red, were applied to the subject, producing the three photographs at right. When the data from the three are added together in the proper proportions, a color image is produced. Our brains, with three different types of cones sending signals from our eyes, do this automatically.

Credit: Sergei Mikhailovich Prokudin-Gorskii

We also want to do our best to be sensitive to objects that are a combination of:

very distant,

very dusty or intrinsically red,

and that can be faint and/or small in angular size,

and even long-exposure photography across all of the optical wavelengths, as conducted from Earth’s surface, is insufficient for revealing most of those objects. There are, once again, a few reasons for this.

The Universe is expanding, and when light travels through the expanding Universe, its wavelength stretched and becomes red, making it more challenging — and eventually, impossible — to observe with instruments that are only sensitive to optical (visible) light.

Many objects are very dusty, many objects are located behind dust-rich regions of our own galaxy, and dust itself is a physical object made out of particles with a range of grain sizes. If you have enough dust, particularly if you have enough dust composed of large enough particles, it will block not just blue light, but potentially all of the visible light from the stars behind it, rendering it again invisible to instruments that are only sensitive to optical (visible) light.

This highlights the importance of not simply looking in optical wavelengths: at the wavelengths our human eyes have evolved to be sensitive to. Instead, it’s important to engage in multiwavelength studies, and in particular to look to longer, infrared wavelengths to reveal the distant, dusty (or obscured by foreground dust), and intrinsically red objects found in our Universe.

Italian astronomer Paolo Maffei’s promising work on infrared astronomy culminated in the discovery of galaxies — like Maffei 1 and 2, shown here — in the plane of the Milky Way itself. Maffei 1, the giant elliptical galaxy at the lower left, is the closest giant elliptical to the Milky Way, yet went undiscovered until 1967. For more than 40 years after the Great Debate, no spirals in the plane of the Milky Way were known, due to light-blocking dust that’s very effective at visible wavelengths.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

The last challenge is that the very faint objects that are both intrinsically small and are located at great distances present a big challenge to any observatory that has to contend with Earth’s atmosphere. Many astronomers describe ground-based astronomy as looking at the Universe from the bottom of a swimming pool, as the atmosphere significantly distorts our views of the Universe. Even with adaptive optics — an impressive technology that significantly counteracts those distortive effects — telescopes, particularly at wavelengths (such as infrared) where atmospheric absorption is efficient, perform far better when they don’t have to contend with the atmosphere.

That’s where going to space becomes incredibly effective. From above Earth’s atmosphere, we don’t have to contend with those light-blocking and light-distorting effects; the photons that we observe simply enter our telescope’s “light bucket” and head into its instruments directly. That’s the tremendous power of space telescopes, as was shown exquisitely in the 1990s with the launch of NASA’s original fleet of great observatories.

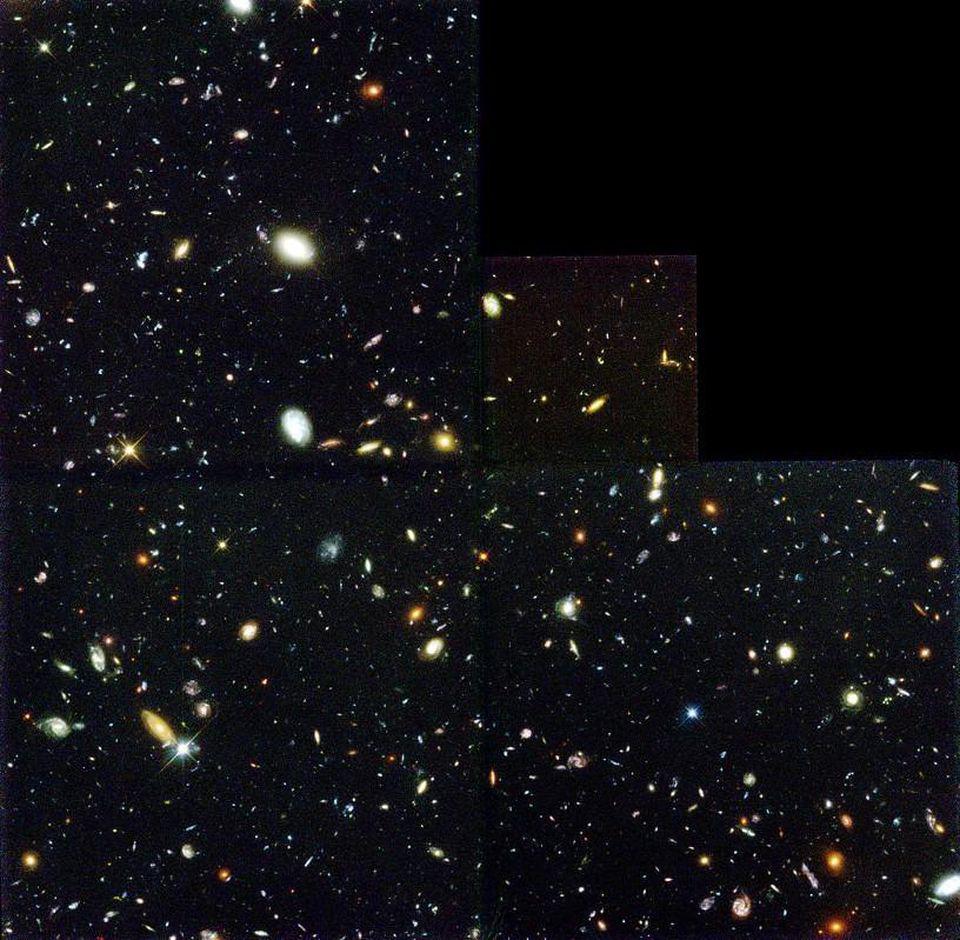

In fact, our original “what the Universe looks like” photo came from the Hubble Space Telescope, when the then-director Bob Williams ordered, in late 1995, that the telescope view a region of space known to contain absolutely nothing for a whopping 342 Hubble orbits, splitting time between four different wavelength filters for the endeavor.

The original Hubble Deep Field image, for the first time, revealed some of the faintest, most distant galaxies ever seen. Around 3000 galaxies were found in this region of space: in a region of sky about as big as a fraction of a postage stamp held at arm’s length. Only with a multiwavelength, long-exposure view of the ultra-distant Universe could we hope to reveal these never-before-seen objects.

Credit: R. Williams (STScI), Hubble Deep Field Team/NASA

The result was immediately iconic: the first Hubble Deep Field image ever acquired. The ultra-distant Universe was revealed for the first time. It wasn’t empty, but rather was filled with galaxies of all types, colors, sizes, and at all distances we were capable of seeing them at. This view wasn’t just inspirational and breathtaking, it helped revolutionize how we understood what was in the Universe, as well as how galaxies grow up throughout cosmic history.

That was more than 30 years ago!

In the time since, we’ve:

introduced new observatories and new instruments,

taken longer-exposure images across even greater wavelength ranges,

acquired less deep imaging over much larger areas of the sky,

and combined deep imaging from several different observatories of the same region,

all of which have helped reveal additional cosmic secrets. We’ve learned what lies inside star-forming regions; we’ve learned where active supermassive black holes reside; we’ve imaged interacting galaxy clusters; we’ve revealed fainter, more distant objects than anything found in the original Hubble Deep Field.

But perhaps the greatest advance that we’ve made in imaging the ultra-distant, ultra-faint Universe has come with the advent of the JWST era. By looking at longer, infrared wavelengths than Hubble ever could, we’ve revealed the young Universe that remained obscure even with every other observatory we’ve ever used.

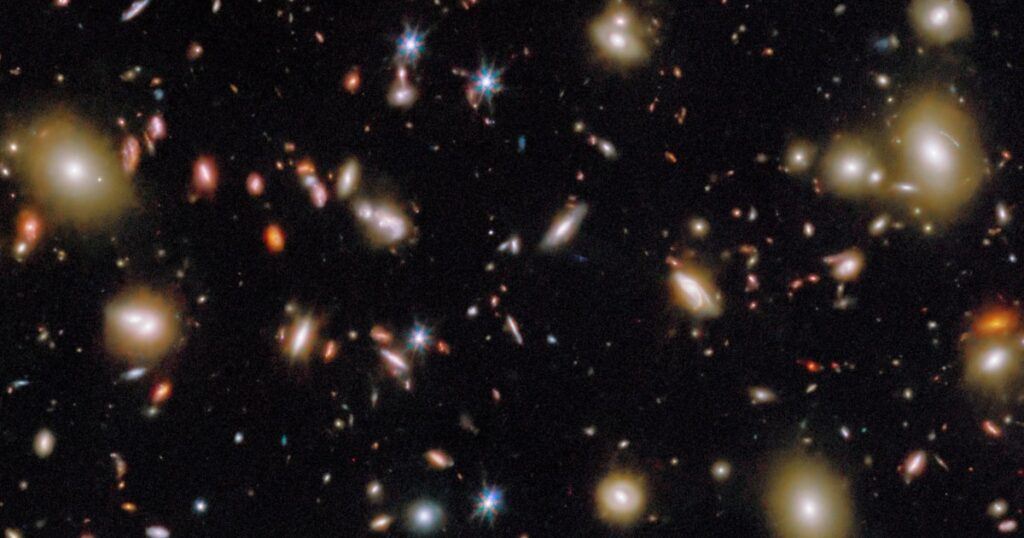

This view showcases the center of cluster SMACS 0723, as seen by both Hubble and JWST. Note how much sharper and better-resolved the central region is with JWST; what looked like a diffuse “smear” with Hubble is now clearly a series of individual objects with JWST. This opens up a whole new realm of discovery in astronomy and astrophysics.

(Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI; NASA/ESA/Hubble (STScI); composite by E. Siegel)

Above, you can see the central portion of the very first JWST image ever released: an image of galaxy cluster SMACS 0723. The “less good” view of it comes from a composite of Hubble imagery, imagery that took about 9.6 hours to acquire, yielding 3.4 hours worth of useful data. On the other hand, the JWST took a total of 12 hours of imagery, and acquired 12 hours worth of useful data.

The JWST data, especially in direct comparison to Hubble, clearly reveals more galaxies, more faint galaxies, galaxies at greater distances, and more well-resolved features within previously known galaxies than the Hubble imagery does. Objects that were invisible to Hubble are easily revealed to JWST; objects that appear blurry to Hubble appear sharp with JWST views; objects that appeared featureless to Hubble have many clear features visible within them as seen by JWST.

The key differences are:

in JWST instrumentation, which is optimized for infrared, rather than optical, imagery,

in JWST’s size, which has about seven times the light-gathering power of Hubble,

in the number of wavelength filters that the telescope can observe in,

and in JWST’s location at the L2 Lagrange point, which allows it to continuously acquire useful data from any target it observed, as opposed to Hubble’s location in low-Earth orbit, which prevents it from observing most targets for at least 50% of its observing time.

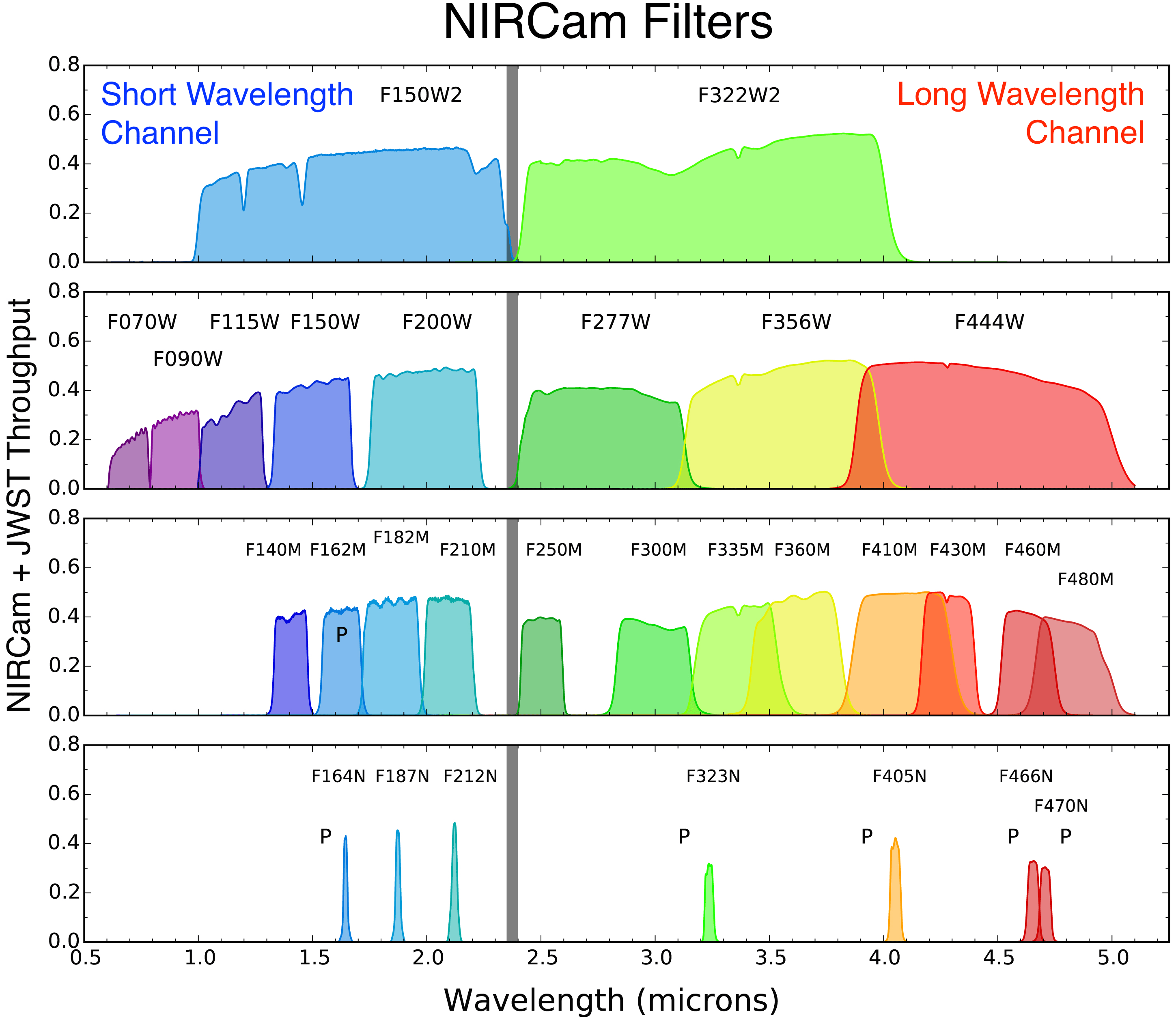

In particular, where Hubble’s longest wavelength that it can usefully observe at is right around 2.0 microns, JWST’s NIRCam and NIRSpec instruments can go all the way to 5.0 microns, whereas its MIRI instrument can go from 5.0 microns all the way out to ~28 microns!

Preliminary total system throughput for each NIRCam filter, including contributions from the JWST Optical Telescope Element (OTE), NIRCam optical train, dichroics, filters, and detector quantum efficiency (QE). Throughput refers to photon-to-electron conversion efficiency. By using a series of JWST filters extending to much longer wavelengths than Hubble’s limit (between 1.6 and 2.0 microns), JWST can reveal details that are completely invisible to Hubble. The more filters that are leveraged in a single image, the greater the amount of details and features that can be revealed.

Credit: NASA/JWST NIRCam instrument team

The “W” filters, or wide-band filters, gather the most light. To find the faintest objects, you need the most light you can gather, total. Meanwhile, to find the most distant objects — or, equivalently, the most severely redshifted objects — what you want to do is:

demonstrate that, at short wavelengths of light, there is no sign of an object there, as below a critical wavelength (multiplied by a factor of “one plus the redshift”), there is no emitted light to see,

whereas, at long wavelengths of light, there is indeed an object there: an object that appears only at long wavelengths because even the shortest emitted wavelengths of light are redshifted to those long wavelengths,

and where you observe a patch of sky for long enough periods of time, you don’t just see the brightest, rarest, most massive objects for that time, but rare, faint objects; objects that can only be revealed with the deepest imagery we’re capable of taking.

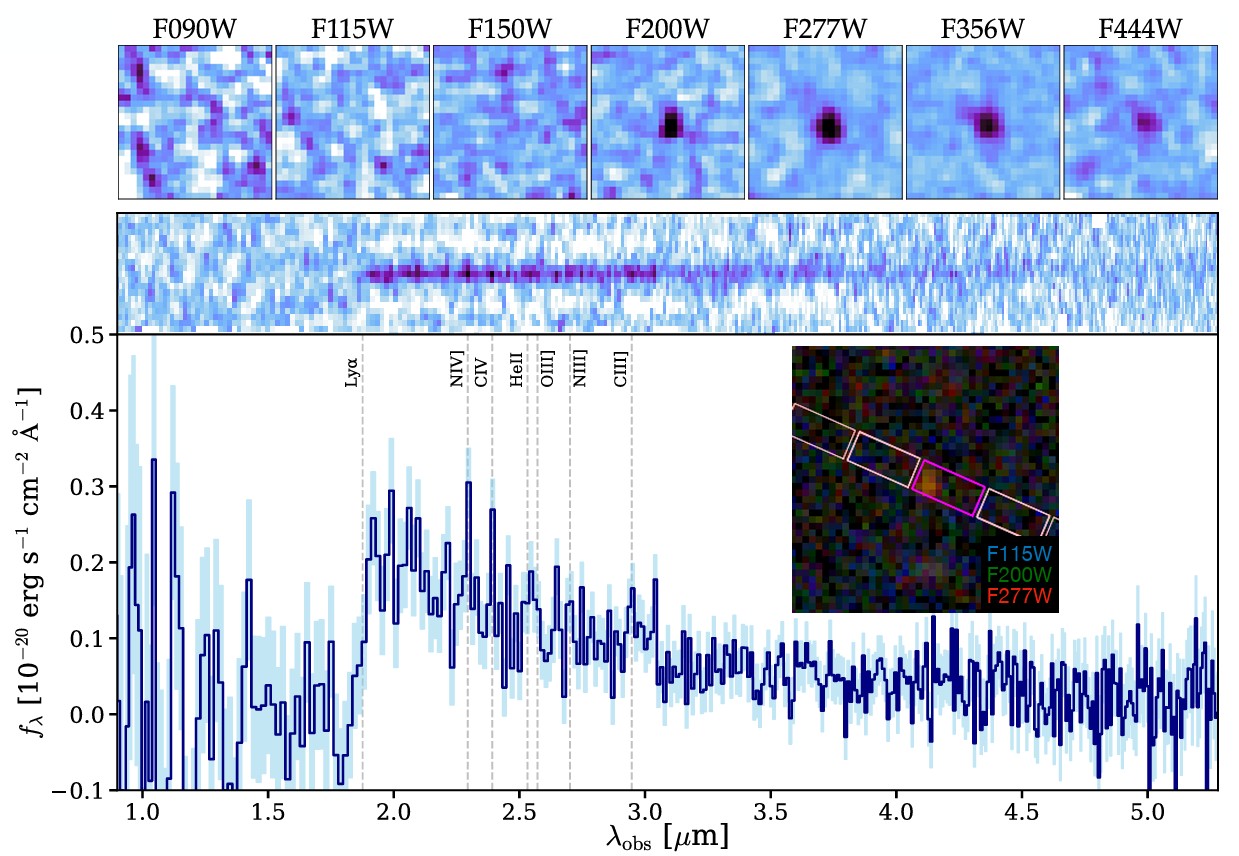

Then, once you identify those candidate objects, the ones that appear the same way that the most distant objects of all would appear in your observatory’s instruments, you do follow-up imaging in spectroscopy mode. This allows you to break up the light from a distant object into its component wavelengths, and if you can see and identify a series of characteristic emission lines, you’ve got it: you’ve got what redshift it’s at.

This figure shows the NIRCam (top) and NIRSpec (bottom) data for now-confirmed galaxy MoM-z14: the most distant galaxy known to date as of May 2025. Completely invisible at wavelengths of 1.5 microns and below, its light is stretched by the expansion of the Universe. Emission features of various ionized atoms can be seen in the spectrum, below, as well as the significant and strong Lyman break feature.

Credit: R.P. Naidu et al., Open Journal of Astrophysics (submitted)/arXiv:2505.11263, 2025

This is the exact technique we’ve already used to find not only the most distant galaxy we’ve ever found — MoM-z14, as shown above — but all 10 of the top 10 most distant galaxies known as of today, here in February of 2026.

But we haven’t truly pushed the limits of JWST to go as deep as possible. The deepest image we ever took with Hubble is known as the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field, and represents 23 days worth of observing time, all of the same region of space. Meanwhile, not a single JWST imaging program has even approached that amount of observing time, including:

CEERS, which was the first early-release science program to survey the distant Universe,

GLASS, which combined deep imagery with the gravitationally lensed field around cluster Abell 2744 to view into the distant Universe,

UNCOVER, which is complementary to GLASS,

JADES, or the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, which has the deepest imagery so far and holds the top few spots for “most distant galaxy” known at present,

and COSMOS-Web, which took up more observing time than any of those other surveys, and still went very deep (but not as deep as the others), and instead provides our best wide-field view with JWST of all-time.

Using the technique of gravitational lensing helps in some ways (more magnification, allowing us to see deeper and fainter objects than normal), but harms in some ways too (reduces the total useful survey area, and enhancements only occur along particular caustic lines). Going wider sacrifices depth. And, perhaps importantly, spending all of your observing time on photometry means that there are many promising ultra-distant galaxy candidates that simply don’t get followed up on the way we’d desire.

Before JWST, there were about 40 ultra-distant galaxy candidates known, primarily via Hubble’s observations. Early JWST results revealed many more ultra-distant galaxy candidates, but now a whopping 717 of them have been found in just the JADES 125 square-arcminute field-of-view. The entire night sky is more than 1 million times grander in scale. While some candidates will survive spectroscopic follow-up, others will not; no candidates at a redshift of 15 or above have survived spectroscopic follow up to date. Much science remains to be conducted, but very few facilities (other than JWST itself) are capable of conducting the needed follow-ups.

Credit: Kevin Hainline for the JADES Collaboration, AAS242

That’s why it’s time to go deep: deeper than we’ve ever gone before with JWST here in the JWST era of the 2020s. We’ve done the wide-field imaging and we’ve done preliminary deep imaging with JWST already, and in many ways they’ve revealed the most profound information we could ask for about the Universe we inhabit today. We’ve observed many areas deeply with Hubble, Chandra, and other great observatories, and with the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, we fully expect to get better, wider-field data just as deeply as Hubble could image, but with ~100 times the area coverage.

There are a great many worthy projects to pursue, and many astronomers are indeed pursuing them. After all, JWST is currently the most oversubscribed space telescope in history, with thousands of high-quality proposals every cycle, of which fewer than 10% get accepted. (In fact, it’s so oversubscribed that even proposals that have gotten perfect scores from reviewers have been rejected, encouraged instead to apply next cycle!)

But the chance to go deeper than ever, to push a new telescope’s limits past where they’ve ever been pushed before, and the opportunity to not just break but to shatter how faint and deep we can go should not be overlooked, and we shouldn’t delay it for very long. The opportunity is there, and the capabilities are there. It’s time to do the bravest thing of all, and look at the Universe as we’ve never looked at it before. After all, beyond the current horizon is always where the most surprising discoveries, if they’re out there at all, are just waiting for us to find them.