Astronomers at Texas A&M University have discovered a rare, tightly packed collision of galaxies in the early universe, suggesting that galaxies were interacting and shaping their surroundings far earlier than scientists had predicted.

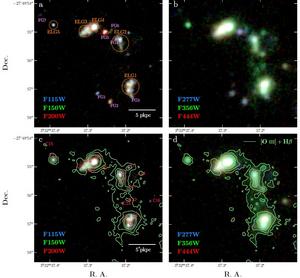

Using observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the researchers identified an ongoing merger event of at least five galaxies about 800 million years after the Big Bang, along with evidence that the collision was redistributing heavy elements beyond the galaxies themselves. Before JWST, astronomers expected complex galaxy mergers and widespread enrichment by oxygen and other products of stellar fusion to become common well over a billion years after the Big Bang. This discovery shows those processes were already underway far earlier than models predicted.

Dr. Weida Hu, a postdoctoral researcher and the study’s lead author, and Dr. Casey Papovich, professor of physics and astronomy, published their findings in Nature Astronomy.

JWST reveals unexpected galaxy merger in the early universe

At that early point in cosmic history, astronomers generally expect galaxies to be relatively small and isolated. Instead, the newly discovered system — dubbed “JWST’s Quintet”— shows multiple galaxies interacting within a compact region of space and surrounded by a halo of oxygen‑rich gas.

“What makes this remarkable is that a merger involving such a large number of galaxies was not expected so early in the universe’s history, when galaxy mergers were thought to simpler and usually involve only two to three galaxies,” Hu said.

Early galaxies formed stars at unusually high rates

The system was identified in data from the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey, one of the deepest imaging campaigns conducted with JWST.

Although the galaxies are separated by tens of thousands of light-years, they occupy an unusually compact region of space and formed stars at a rate about 250 times the mass of the sun per year, far higher than typical galaxies at that time.

Galaxy collisions spread heavy elements into surrounding space

The researchers also detected an extended halo of glowing gas linking several of the galaxies. The gas emits light from ionized oxygen and hydrogen. The surprising result is that this gas lies outside the galaxies. The elements, such as oxygen, are only produced inside stars and later removed from the galaxies during the collision.

The team’s analysis suggests the enrichment was driven primarily by gravitational interactions during the merger, rather than by galactic winds alone, providing direct evidence that galaxy collisions were shaping their surrounding environments in the young universe.

Discovery challenges models of early galaxy evolution

Papovich notes this discovery matters because it helps explain a growing mismatch between what astronomers’ models predict and what JWST is actually observing.

“By showing that a complex, merger-driven system exists so early, it tells us our theories of how galaxies assemble — and how quickly they do so — need to be updated to match reality,” Papovich said.

The discovery may help explain why JWST has identified a growing number of massive galaxies that appear largely inactive just a few billion years later. If systems like JWST’s Quintet merged rapidly and exhausted their gas early, they could evolve into those massive galaxies seen at later times.

Future JWST observations will examine the motion of gas and galaxies within the system, offering additional insight into how early cosmic structures formed.

Additional Texas A&M authors on the paper are: Dr. Lu Shen, postdoctoral research associate; Dr. Justin Spilker, assistant professor; and Justin Cole, Ph.D. student. This research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, NASA and Marsha and Ralph Schilling.

By Lesley Henton, Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications

###

Disclaimer: AAAS and EurekAlert! are not responsible for the accuracy of news releases posted to EurekAlert! by contributing institutions or for the use of any information through the EurekAlert system.