Right after the universe began, nothing looked familiar. Space was packed with heat and motion. Matter had not yet settled into atoms or even protons.

Instead, everything existed in a frantic state made of the smallest building blocks, racing around at nearly the speed of light.

This phase did not last long. It flickered by in the first microseconds, then cooled just enough for the matter we know today to take shape.

That brief moment still matters. It set the rules for how particles behave, how forces work, and why the universe looks the way it does now.

Physicists have spent decades trying to understand this early state, not by traveling back in time, but by rebuilding pieces of it in the lab.

The universe’s first liquid

One of the strangest things about the early universe is that it likely contained the first liquid ever to exist. This liquid, called quark-gluon plasma, formed when quarks and gluons moved freely in an extremely hot, dense mix.

Scientists estimate its temperature reached a few trillion degrees Celsius, making it the hottest liquid ever observed.

To study it, researchers collide heavy atomic nuclei at close to the speed of light. These crashes briefly melt protons and neutrons back into quarks and gluons, creating a tiny droplet of that ancient plasma.

The droplet exists for less than a quadrillionth of a second, but modern detectors can still capture detailed data from the moment it forms.

When fast particles leave a trace

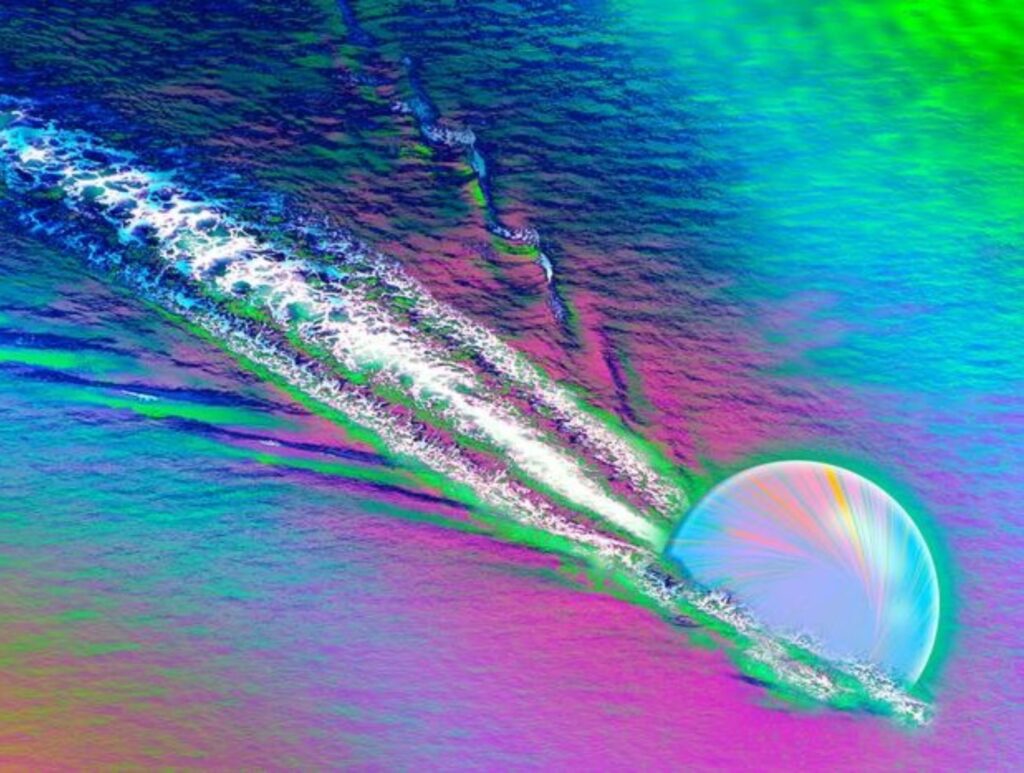

For years, physicists debated how this plasma behaves. Does it act like a loose swarm of particles, or does it move together as a fluid? One key test involved watching what happens when a single quark blasts through the plasma.

The work was led by physicists at MIT using data from CERN’s Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland. Their results point strongly toward fluid behavior.

“It has been a long debate in our field, on whether the plasma should respond to a quark,” said Yen-Jie Lee, professor of physics at MIT.

“Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark, and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup.”

A clever way to spot a single quark

Seeing the effect of just one quark is harder than it sounds. Quarks often appear in pairs moving in opposite directions, and their effects overlap. That overlap can hide the very signal scientists want to measure.

The team solved this by focusing on collisions that produce a quark and a Z boson.

A Z boson passes through the plasma without disturbing it and appears at a specific energy that detectors can easily recognize.

The quark, on the other hand, interacts strongly with the plasma. Any motion seen opposite the Z boson can be linked directly to the quark.

“We have figured out a new technique that allows us to see the effects of a single quark in the QGP, through a different pair of particles,” said Lee.

What billions of collisions revealed

The researchers sifted through data from 13 billion heavy-ion collisions. Among them, they found about 2,000 events that produced a Z boson.

In those cases, the team mapped how energy spread through the plasma and found clear patterns that matched a wake created by a single fast-moving quark.

“In this soup of quark-gluon plasma, there are numerous quarks and gluons passing by and colliding with each other,” noted Lee.

“Sometimes when we are lucky, one of these collisions creates a Z boson and a quark, with high momentum.”

The observed wake patterns lined up with long-standing theoretical predictions. One of those predictions came from a hybrid model that suggested the plasma should respond like a fluid when struck by a fast particle.

“This is something that many of us have argued must be there for a good many years, and that many experiments have looked for,” said Krishna Rajagopal, a professor of physics at MIT.

“We’ve gained the first direct evidence that the quark indeed drags more plasma with it as it travels,” said Lee. “This will enable us to study the properties and behavior of this exotic fluid in unprecedented detail.”

What the early universe was like

These results give scientists a clearer window into the universe’s earliest moments. By measuring how quark wakes form, spread, and fade, researchers can better pin down the properties of quark-gluon plasma and how it once filled all of space.

“Studying how quark wakes bounce back and forth will give us new insights on the quark-gluon plasma’s properties,” said Lee. “With this experiment, we are taking a snapshot of this primordial quark soup.”

That snapshot captures a time when matter behaved in ways that no longer exist naturally. Understanding it brings physicists one step closer to explaining how the universe grew up from chaos into structure.

The full study was published in the journal Physics Letters B.

Image Credit: Jose-Luis Olivares, MIT

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–