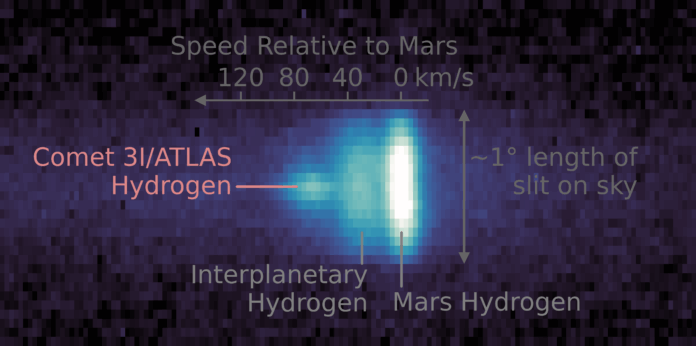

Ultraviolet spectrographic visualization showing hydrogen emissions near Mars, including contributions initially attributed to interplanetary and Martian hydrogen. Later analysis suggests cometary hydrogen was underestimated. (Image credit: NASA/MAVEN; illustrative use under fair use for news reporting, 17 U.S.C. §107)

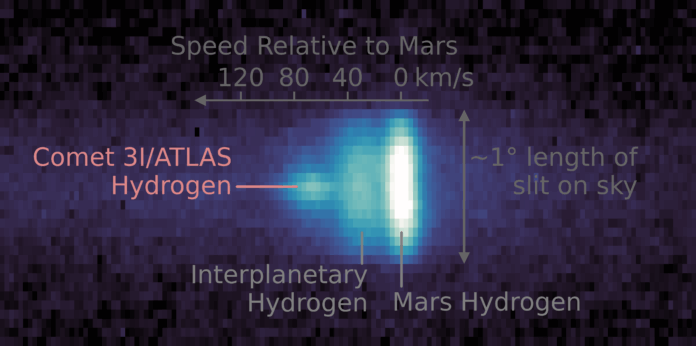

Ultraviolet spectrographic visualization showing hydrogen emissions near Mars, including contributions initially attributed to interplanetary and Martian hydrogen. Later analysis suggests cometary hydrogen was underestimated. (Image credit: NASA/MAVEN; illustrative use under fair use for news reporting, 17 U.S.C. §107)

INSIDE THIS REPORT

In September 2025, NASA quietly published a spectral image of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS that appeared to simplify a complex and unfamiliar object into something comfortably understood.

That image suggested the comet’s hydrogen emissions were modest, predictable, and largely indistinguishable from background interplanetary hydrogen near Mars.

Five months later, with new observations in hand and NASA again constrained by a partial government shutdown, that early confidence is increasingly difficult to defend.

An early hydrogen signature once used to normalize 3I/ATLAS now highlights how evolving data—and a government shutdown—are complicating planetary defense confidence.

[USA HERALD] – In September 2025, NASA released an annotated ultraviolet spectrographic image of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, derived from observations by the MAVEN mission orbiting Mars. At the time, the image was presented as evidence that the comet’s hydrogen emissions were weak, diffuse, and broadly consistent with known models of cometary outgassing interacting with the solar wind.

The visualization appeared to show a relatively compact hydrogen distribution, partially blended into the broader background of interplanetary hydrogen and Mars’ own extended hydrogen corona. NASA’s interpretation implicitly supported a narrative that 3I/ATLAS, while interstellar in origin, behaved much like a conventional comet once inside the inner solar system.

That interpretation no longer holds.

Subsequent observations made between late 2025 and January 2026—using both space-based ultraviolet instruments and high-sensitivity ground-based imaging—have revealed that the hydrogen environment around 3I/ATLAS is neither stable nor modest. Instead, the comet has demonstrated time-variable hydrogen production, asymmetric expansion patterns, and velocity components that exceed what early models predicted.

Critically, the September image assumed that most of the detected hydrogen could be cleanly separated into three categories: Mars hydrogen, interplanetary background hydrogen, and a small contribution from the comet itself. New data now indicate that this separation was overly optimistic. Hydrogen attributed to background sources appears to have been partially comet-derived, meaning the comet’s true output was likely underestimated.

Velocity measurements are another area where early assumptions have eroded. The original image mapped hydrogen speeds relative to Mars that clustered near lower values. More recent analyses show broader velocity distributions, suggesting higher-energy release processes—possibly driven by volatile species beyond water ice, including hydrogen-rich compounds that were not fully incorporated into NASA’s early thermal models.

In plain terms, NASA treated the September 2025 hydrogen map as a snapshot of a steady system. It was not. It was a moment in a dynamic and evolving interaction between an interstellar object and the solar environment—one that scientists are now racing to recharacterize.

This matters because hydrogen emission is not just a visual curiosity. It is a proxy for mass loss, internal composition, and structural integrity. Underestimating hydrogen production leads directly to underestimating how an object sheds material, how it responds to solar heating, and how its trajectory and physical structure may evolve over time.

The implications extend beyond academic modeling. As 3I/ATLAS approaches its March 16, 2026 encounter with Jupiter, accurate predictions about outgassing behavior will be essential. Jupiter’s immense gravity can amplify structural weaknesses, alter rotation states, and dramatically reshape a small body’s future path. If early hydrogen estimates were low, then earlier risk assessments were incomplete.

Compounding these scientific challenges is the reality that, as of February 1, 2026, the U.S. government is operating under a partial government shutdown. While essential NASA operations continue, non-essential analysis, public communication, and cross-agency coordination are often delayed or deprioritized during funding lapses. Historically, shutdowns have slowed data releases, postponed peer review processes, and reduced transparency at precisely the moments when clarity is most needed.

That context matters. The September 2025 image was released during a period of constrained attention and limited follow-up. Today, NASA finds itself again navigating fiscal uncertainty while attempting to update the public on a rapidly evolving interstellar object that challenges existing assumptions.

NASA has not stated that its early interpretation was wrong. But the growing gap between what that image implied and what current data now show suggests the agency’s initial models were incomplete at best.

USA HERALD’S ANALYSIS AND CONTEXTUAL INSIGHT

The lesson embedded in this image is not that NASA failed to detect 3I/ATLAS—it is that early normalization can be as risky as outright dismissal. By fitting an unfamiliar interstellar object into familiar cometary frameworks too quickly, critical anomalies were effectively smoothed over.

For planetary defense, this raises uncomfortable questions. Detection is only the first step. Interpretation, modeling, and timely reassessment are where preparedness either holds—or collapses. If an interstellar object with unusual chemistry and evolving behavior can be underestimated for months, the margin for error in a closer, faster, or more massive future visitor narrows considerably.

The September 2025 hydrogen image of 3I/ATLAS was once a symbol of reassurance. Today, it reads more like a warning about the limits of early assumptions, especially under institutional and political constraints. As new data continues to reshape our understanding of this object, the story of 3I/ATLAS underscores a simple reality: space does not pause for budget negotiations, and neither should scientific vigilance.