In a groundbreaking effort to study the Sun up close, NASA’s Parker Solar Probe has captured unprecedented data on the source of the solar wind. A research team led by the University of Arizona has now used these findings to reveal how this hot plasma behaves near the star’s surface.

Published in Geophysical Research Letters, the study highlights detailed measurements from the spacecraft’s closest encounters with the Sun, narrowing in on a volatile boundary of gas and magnetic fields. These insights could significantly refine our understanding of solar weather, which affects not only our planet but every world in the solar system and beyond.

According to Kristopher Klein, a physicist at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, understanding the Sun’s atmosphere is key to predicting when and how these disturbances will reach Earth. Before Parker, such predictions were based on incomplete models that lacked real-time, close-range measurements.

Closing In On The Sun’s Outer Atmosphere

The Parker Solar Probe, launched in 2018, is flying a looping path around the Sun with help from gravity assists via Venus. During its record-breaking close pass just 3.8 million miles from the solar surface, the probe captured high-resolution data on the Sun’s corona, a faint halo of superheated gas that extends millions of miles into space.

As reported by the University of Arizona, this region shows surprising thermal behavior. Plasma moving outward from the Sun’s core cools significantly in the visible photosphere, reaching around 10,000°F, then unexpectedly heats up again in the outer corona, exceeding 2 million°F. This heating is driven by interactions between charged particles and intense magnetic fields, some of which bend, twist, or violently snap back on themselves.

Until now, researchers could only speculate on these dynamics using indirect observations and simplified particle models. The probe’s close-range readings have allowed them to study these regions directly, offering the clearest look yet at where and how the solar wind is formed.

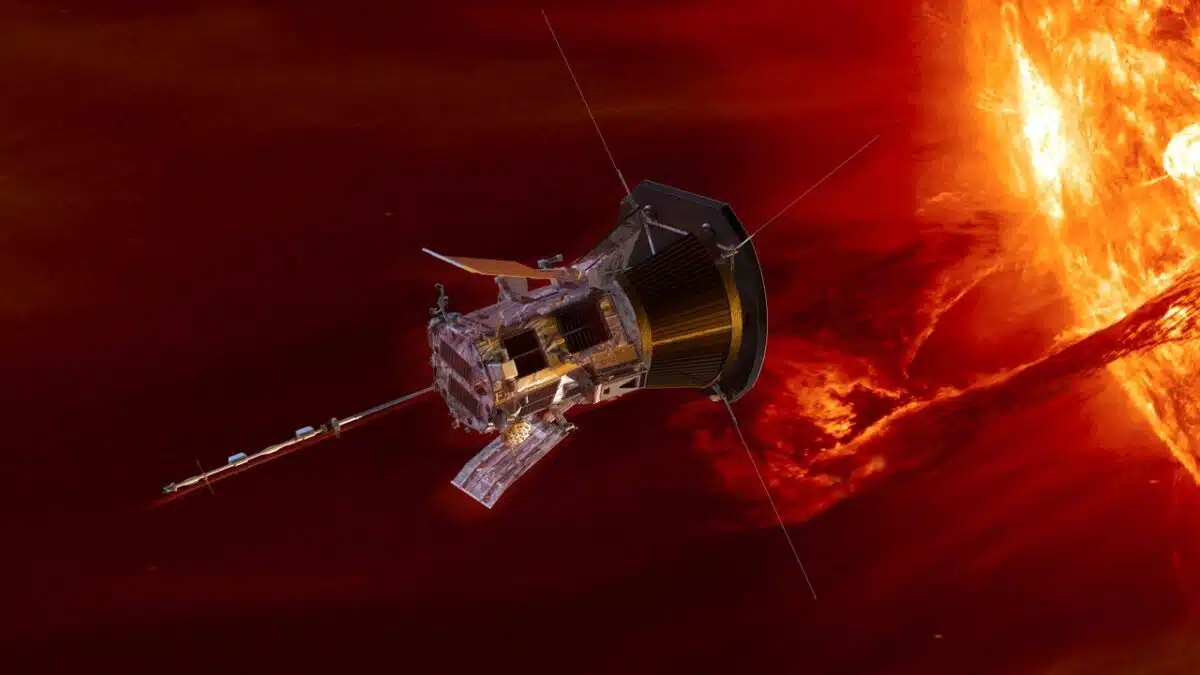

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe approaching the Sun’s corona, where the solar wind originates. Credit: NASA/APL

NASA’s Parker Solar Probe approaching the Sun’s corona, where the solar wind originates. Credit: NASA/APL

Decoding Particle Behavior With ALPS

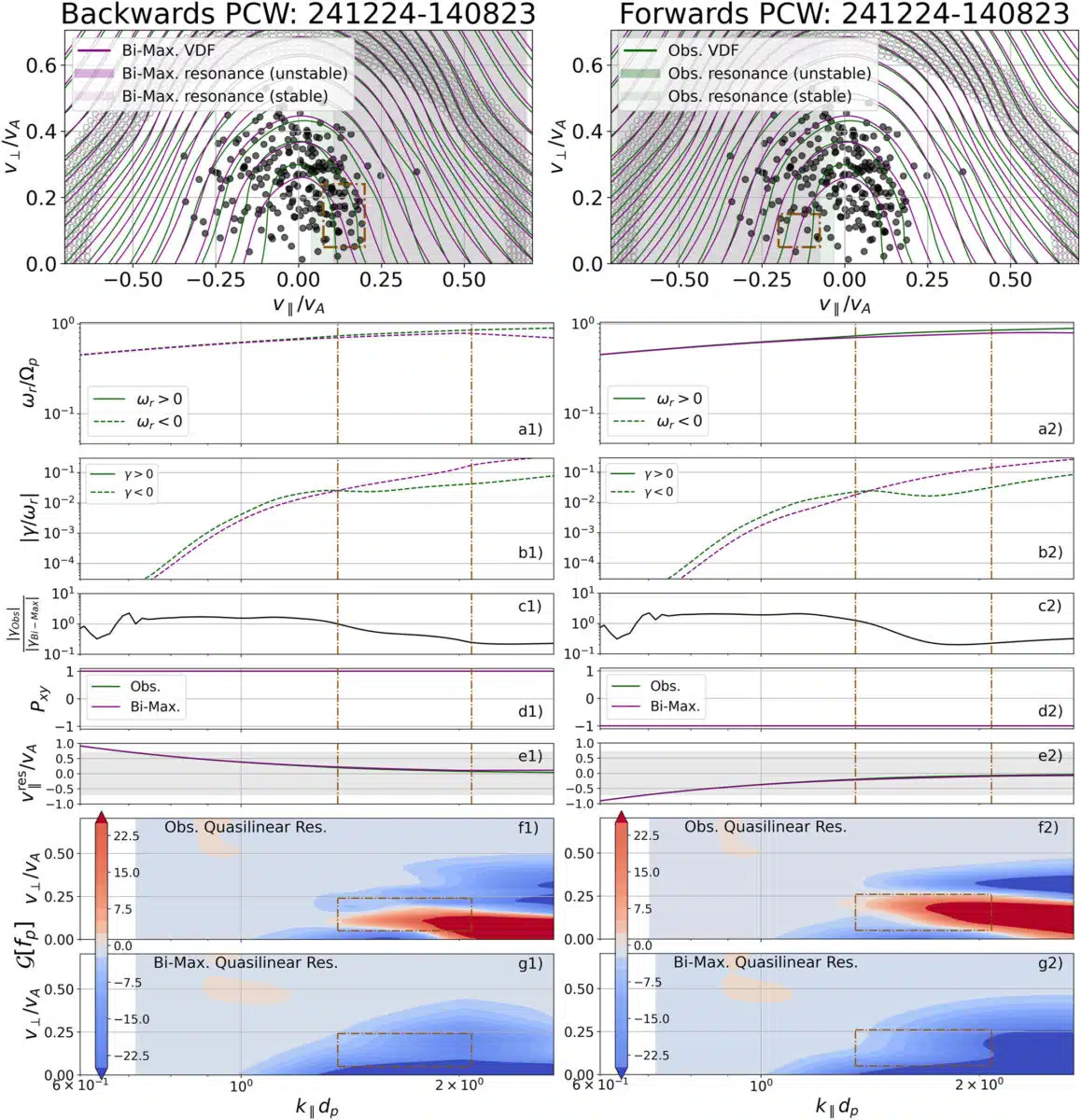

To make sense of the probe’s data, Klein’s team developed a new computational tool: the Arbitrary Linear Plasma Solver (ALPS). This code allowed them to analyze how different particles, measured individually by the spacecraft, respond to waves moving through the Sun’s plasma. Instead of relying on general assumptions, they could now assess how the actual velocity distributions of particles affect energy transfer.

“We know there’s this constant heat that’s being input into the solar wind,” said Klein, “and we want to understand what mechanisms are actually leading to that heating.”

Based on the team’s findings, previous estimates had to rely on simplified models. Now, with real measurements in hand, scientists can map exactly where this heating happens as the particles escape the Sun.

One of the study’s findings is that particles cool down much more gradually than expected as they move away from the solar surface. This phenomenon, known as damping, is not yet fully understood. But it adds another layer to how energy is transferred and retained in the Sun’s expanding atmosphere.

Comparison of backward and forward propagating plasma waves observed by Parker Solar Probe. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters

Comparison of backward and forward propagating plasma waves observed by Parker Solar Probe. Credit: Geophysical Research Letters

What Starts at the Sun Doesn’t Stay at the Sun

The ability to measure heating and damping in solar particles has major implications for understanding space weather. As stated by Klein, improved models will help researchers forecast how coronal mass ejections and other solar events propagate through space and eventually interact with Earth’s magnetic field.

These eruptions can have measurable impacts, from knocking out communications satellites to increasing radiation exposure for aircraft flying near the poles. For scientists and engineers alike, knowing what’s coming and when is becoming more than just an academic pursuit. Perhaps more importantly, the processes uncovered by Parker are not unique to our Sun. As the research team reports:

“If we can understand the damping in the solar wind, we can then apply that knowledge of energy dissipation to things like interstellar gas, accretion disks around black holes, neutron stars and other astrophysical objects.”

By studying our own star’s behavior in such detail, the findings could lay the groundwork for exploring similar systems across the universe.