In the final moments before two neutron stars collide, their magnetic fields spiral into chaos, twisting and snapping as they unleash high-energy radiation into space. Using a NASA supercomputer, scientists have now simulated this violent prelude in unprecedented detail and uncovered potential light signals that might soon be detectable by space telescopes.

The research focuses on the final milliseconds before merger, a phase long overshadowed by the dramatic aftermath of these stellar collisions. By mapping the interactions of the neutron stars’ magnetospheres, researchers have identified specific gamma-ray and X-ray emissions that could serve as early indicators of an impending cosmic impact.

The Final Magnetic Dance Before Merger

The team ran more than 100 simulations on NASA’s Pleiades supercomputer to test how different neutron star magnetic field configurations shape the electromagnetic energy released in the final 7.7 milliseconds before merger. In the last orbits, their magnetospheres act like a “magnetic circuit” that continually rewires itself. Field lines stretch, snap, and reconnect, releasing energy, driving plasma to near light speed, and producing brief radiation bursts.

In these final orbits, the neutron stars’ magnetospheres become intensely active. As described by NASA, they behave like “a magnetic circuit that continually rewires itself.” Magnetic field lines stretch between the two stars, then break and reconnect, releasing energy and accelerating plasma close to the speed of light. These interactions generate short bursts of radiation that, depending on the stars’ orientation, might be visible from Earth.

The researchers observed that these emissions are far from uniform. Some angles show bright flares while others appear dark. Zorawar Wadiasingh, another team member from the University of Maryland, explained that the orientation of the stars’ magnetic fields plays a decisive role in what an observer might see.

“The signals also get much stronger as the stars get closer and closer in a way that depends on the relative magnetic orientations of the neutron stars.”

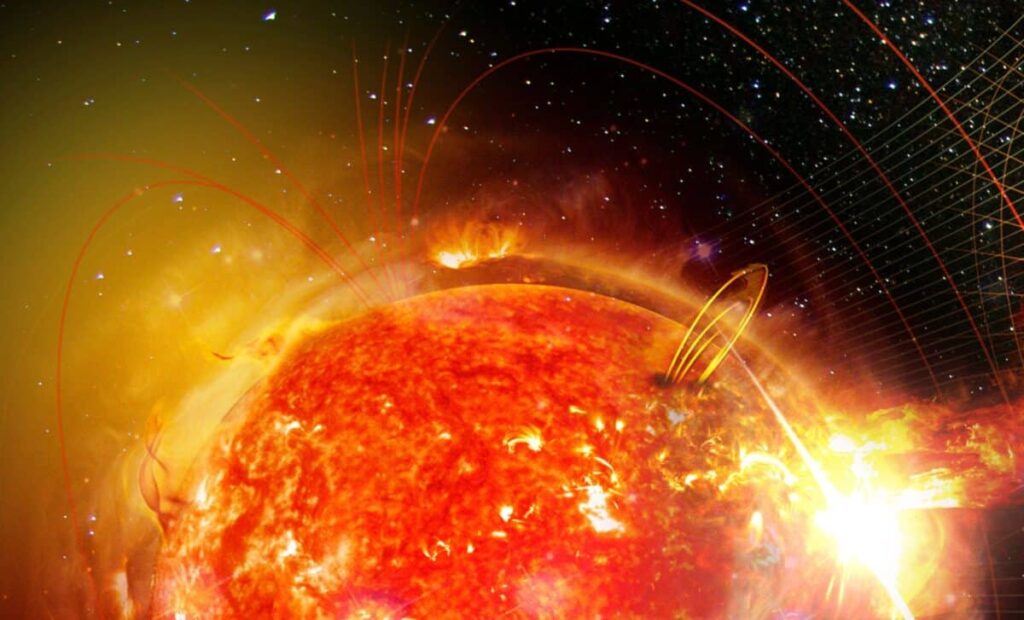

NASA simulation of two neutron stars nearing collision amid magnetic turbulence. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas & al.

NASA simulation of two neutron stars nearing collision amid magnetic turbulence. Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/D. Skiathas & al.

High-energy Light Trapped And Released

The simulations revealed a storm of gamma-ray activity, including emissions at energies trillions of times greater than visible light. However, according to the findings reported by The Astrophysical Journal, these ultra-high-energy photons are quickly absorbed and converted into matter, specifically electron-positron pairs, by the stars’ powerful magnetic fields. As a result, most of that energy never escapes.

But emissions at lower gamma-ray energies, millions of times stronger than visible light, do have a chance to break free. These signals could be detected by medium-energy gamma-ray and X-ray telescopes, provided they are alerted in time. The simulations identified the regions where such emissions are likely to form based on how the magnetic fields and plasma behave in the seconds leading up to the crash.

Instruments that can detect curvature radiation, a phenomenon where high-speed electrons spiral along curved magnetic field lines and emit gamma rays, may be best positioned to catch these signals.

Preparing For A New Era Of Early Alerts

While current gravitational-wave observatories such as LIGO and Virgo can detect neutron star mergers in their final moments, this study points toward a future where events can be observed before they peak. According to NASA scientist Demosthenes Kazanas/

“Such behavior could be imprinted on gravitational wave signals that would be detectable in next-generation facilities. One value of studies like this is to help us figure out what future observatories might be able to see and should be looking for in both gravitational waves and light,”

A space-based observatory like LISA, the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna developed by ESA and NASA and planned for launch in the 2030s, will be able to spot these systems long before they collide. If gravitational wave alerts can be delivered early, wide-field telescopes in orbit may have the opportunity to catch the light shows predicted in this study.