In the summer of 1969, Issyk-Kul was quiet in the way large lakes can be—flat water, long horizons, nothing dramatic on the surface. The area was under Soviet control, officially classified as sensitive. Fishing zones were regulated. Certain stretches were simply off-limits. Locals knew where not to ask questions.

The man went missing in the early hours, before the wind picked up. He had gone out alone, which wasn’t unusual then. His boat was later found drifting, engine intact, no visible damage. Nets were still in the water. There were no signs of a struggle. No blood. No torn gear. It looked less like an accident and more like an interruption.

When the search began, it stayed close to shore. Not because the lake was shallow—Issyk-Kul isn’t—but because deeper searches required clearance. That clearance never came. The official explanation was routine: presumed drowning. File closed.

But the divers who were there told a different version years later, quietly, never on record. One of them said the visibility dropped suddenly, as if something in the water absorbed the light. Another mentioned movement below the thermocline, too large and too deliberate to be fish. They were ordered to surface. The dive was terminated.

No body was recovered.

What makes the incident linger isn’t just the disappearance. It’s the way it was handled. No extended search. No follow-up. No local press. For a lake with regular civilian activity, the silence was noticeable. People noticed it then, even if they didn’t say it out loud.

In the following months, a few similar disappearances were mentioned in passing—never officially linked, never formally acknowledged. Different villages, same lake. The details didn’t match perfectly, but the pattern felt familiar enough to unsettle those who depended on the water.

Issyk-Kul had stories long before the Soviets arrived. That’s not the point here. This wasn’t a legend, and it wasn’t framed as one at the time. It was treated as an administrative inconvenience. Something that needed to be concluded, not explained.

What remains today is a gap. No open files. No photographs. Just fragments from people who were present and learned, very early, not to push the question too far.

Note: Issyk-Kul was subject to restricted military oversight during much of the Soviet period. Incidents occurring within controlled zones were often resolved internally and never entered public archives. This account is based on regional testimonies, secondary research notes, and the absence of corresponding open records.

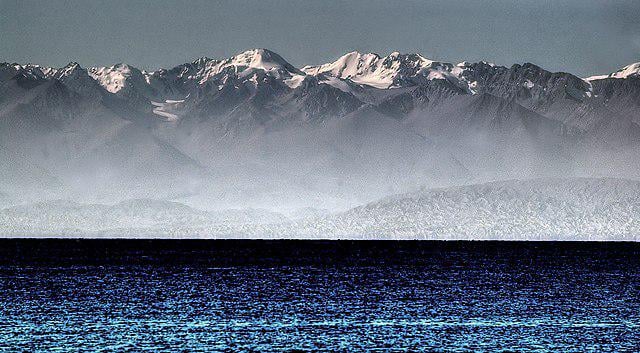

Image credit: Thomas Depenbusch (Depi) — Issyk-Kul, Kyrgyzstan

Licensed under CC BY 2.0

by bortakci34