It’s been 54 years since the last Apollo mission, and since then, humans have not ventured beyond low-Earth orbit. But that’s all about to change with next week’s launch of the Artemis II mission from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

This is the first crewed flight of NASA’s Artemis program and the first time since 1972 that humans have ventured to the moon. Onboard is Canadian astronaut Jeremy Hansen, who will be the first non-American to fly to the moon and will make Canada only the second country in the world to send an astronaut into deep space.

Read more:

Canada’s space technology and innovations are a crucial contribution to the Artemis missions

I am a professor, an explorer and a planetary geologist. For the past 15 years, I have been helping to train Hansen and other astronauts in geology and planetary science. I am also a member of the Artemis III Science Team and the principal investigator for Canada’s first ever rover mission to the moon.

NASA’s Artemis II SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft secured to the mobile launcher at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

(NASA)

What will the mission achieve?

NASA’s Artemis program, launched in 2017, has the ambitious goal to return humans to the moon and to establish a lunar base in preparation for sending humans to Mars. The first mission, Artemis I, launched in late 2022. Following some delays, Artemis II is scheduled for launch as early as a week from now.

Onboard will be Hansen, along with his three American crew-mates.

This is an incredibly exciting mission. Artemis II is the first time humans have launched on NASA’s huge SLS (Space Launch System) rocket, and the first time humans have flown in the Orion spacecraft.

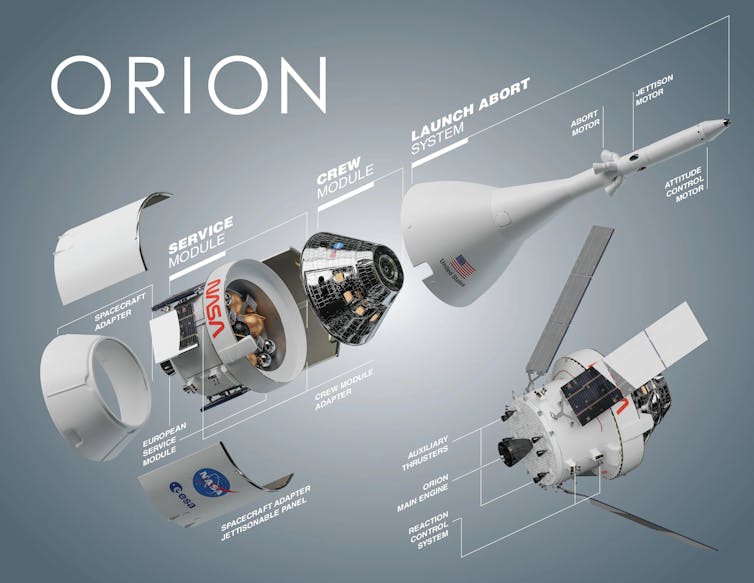

SLS is the most powerful rocket NASA has ever built, with the capability to send more than 27 metric tonnes of payload — equipment, instruments, scientific experiments and cargo — to the moon. The Orion spacecraft sits at the very top and is the crew’s ride to the moon. The Artemis II crew named their Orion capsule Integrity, a word they say embodies trust, respect, candour and humility.

An infographic produced by NASA showing the different parts of the Orion spacecraft.

(NASA)

What will Artemis II crew do in space?

Following launch, the crew will carry out tests of Integrity’s essential life-support systems: the water dispenser, firefighting equipment, and, of course, the toilet. Did you know there was no toilet on the Apollo missions? Instead, the crews used “relief tubes.”

If everything looks good, the Artemis II will ignite what’s known as the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage — part of the SLS rocket still connected to Integrity — to elevate the spacecraft’s orbit. If things are still looking good, the Orion spacecraft and its four human travellers will spend 24 hours in a high-Earth orbit up to 70,000 kilometres away from the planet.

For comparison, the International Space Station orbits the Earth at a mere 400 kilometres.

Following a series of tests and checks, the crew will conduct one of the most critical stages of the mission: the Trans-Lunar Injection, or TLI. This is the crucial moment that changes a spacecraft from orbiting the Earth — where the option to quickly return home remains — to sending it on its way to the moon and into deep space.

The Artemis II mission’s 10-day ‘figure-eight’ trajectory.

(NASA)

Once the Integrity is on its way to the moon after TLI, there is no turning back — at least, not without going to the moon first. That’s because Artemis II — like the early Apollo missions — enters what’s called a “free-return trajectory” after the TLI. What this means is that even if Integrity’s engines fail completely, the moon’s gravity will naturally loop the spacecraft around it and aim it towards Earth.

After the three-day journey to the moon, the crew will carry out perhaps the most exciting stage of the mission: lunar fly-by. Integrity will loop around the far side of the moon, passing anywhere from 6,000 to 10,000 kilometres above its surface — much farther than any Apollo mission.

To quote Star Trek, at that most distant point, the Artemis II crew will have boldly gone where no (hu)man has gone before. This will be, quite literally, the farthest from Earth that any human being has ever travelled.

International effort to explore the moon

That a Canadian astronaut is part of the crew of Artemis II is a testament to the collaborative international nature of the Artemis program.

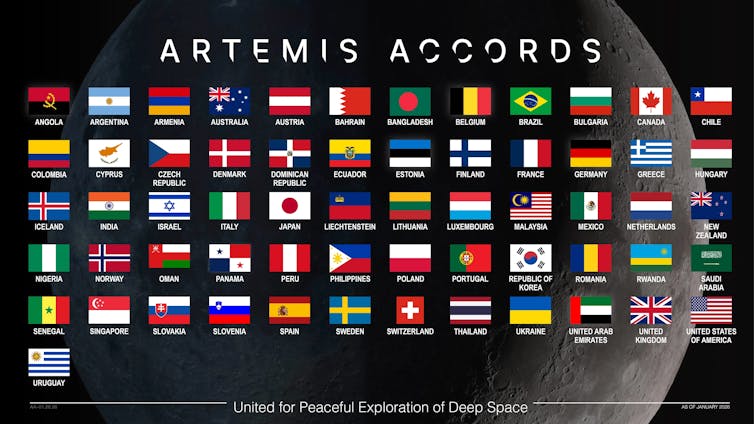

While NASA created the program and is the driving force, there are now 60 countries that have signed the Artemis Accords.

On Jan. 26, 2026, Oman became the 61st nation to sign the Artemis Accords.

(NASA)

The foundation for the Artemis Accords is the recognition that international co-operation in space is intended not only to bolster space exploration but to enhance peaceful relationships among nations. This is particularly necessary now — perhaps more than any other time since the Cold War.

I truly hope that as Integrity returns from the moon’s far side, people around the world will pause — at least for a few moments — and be united in thinking of a better future. As American astronaut Bill Anders, who flew the first crewed Apollo mission to the moon, once said:

“We came all this way to explore the moon, and the most important thing is that we discovered the Earth.”