In a flat-bottomed valley 20 kilometres south of Penticton, B.C., Canada’s most ambitious radio telescope is growing.

An empty field is sprouting white radio dishes, each six metres across with a tent-like cover to keep off the snow. From a distance they dot the landscape like a crop of giant mushrooms – 37 as of last week. By next year, astronomers aim to carpet the site with 512 of them.

“The whole intent is to design something that can be rapidly scaled up,” said project scientist Kendrick Smith, a cosmologist at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Waterloo, Ont. In principle, he added, “there’s nothing to stop us from just continuing.”

Call it the Henry Ford approach to cosmic exploration. Each dish is like the iconic Model T: identical, affordable and capable of being mass produced.

The difference is that when hundreds of them are linked together, they can operate as a single receiver that vacuums up radio waves across billions of light years of space and turns their static hiss into a symphony of cosmic revelation.

Once this radio telescope array is completed near Penticton, B.C., scientists hope it will be a valuable tool for studying deep space. Each group of three pylons will, at some point, support a dish antenna: In this footage from November, many pylons were bare, but fewer so when The Globe returned in January.

That’s the mission of CHORD – the Canadian Hydrogen Observatory and Radio-transient Detector. It’s a unique, homegrown effort that could be the most precise radio telescope of its kind ever.

If so, astronomers can use it to tackle questions that are more typically the domain of major international observatories that cost billions of dollars to build. CHORD is aiming to do it on a budget of $23-million, and do it in a way that puts Canadian scientists in the driver’s seat.

“In my view it’s a coming of age,” said Matt Dobbs, project director of CHORD and a professor of physics at McGill University. “We’re creating something end to end and we’re thinking big about it.”

Big means the project costs enough that Canada is only going to make one such instrument, he added, “and if it fails, we’re in trouble.”

If CHORD succeeds, however, it could achieve something even more impressive than transforming our understanding of the universe: It could help to make Canada’s research support system just a little more daring.

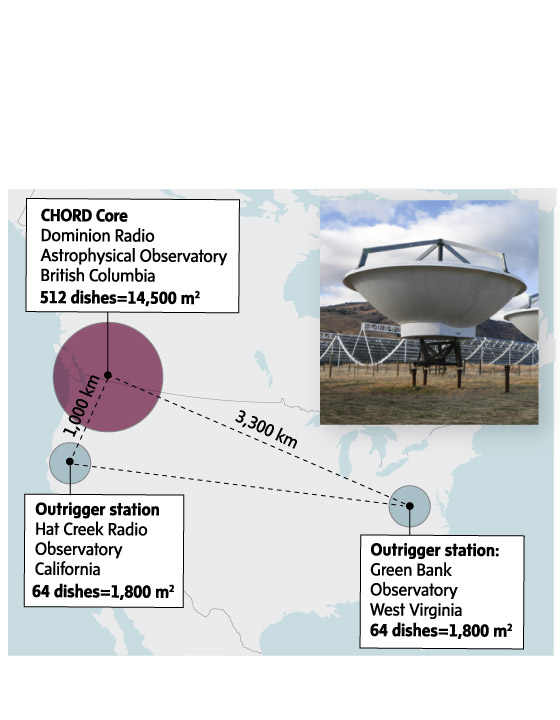

When completed, the Canadian Hydrogen Observatory and Radio-

transient Detector (CHORD) will include the core array near Penticton,

B.C., along with two “outriggers” at locations in the United States.

When working together, the widely spaced stations will be able to

observe distant radio sources with higher precision than the

core site alone.

ivan semeniuk and john sopinski/the globe and mail photo: Aaron

Hemens / The Globe and MailSource: Juan Mena-Parra,

University of Toronto

When completed, the Canadian Hydrogen Observatory and Radio-

transient Detector (CHORD) will include the core array near Penticton,

B.C., along with two “outriggers” at locations in the United States.

When working together, the widely spaced stations will be able to

observe distant radio sources with higher precision than the

core site alone.

ivan semeniuk and john sopinski/the globe and mail photo: Aaron

Hemens / The Globe and MailSource: Juan Mena-Parra,

University of Toronto

When completed, the Canadian Hydrogen Observatory and Radio-transient Detector (CHORD) will

include the core array near Penticton, B.C., along with two “outriggers” at locations in the United States.

When working together, the widely spaced stations will be able to observe distant radio sources with

higher precision than the core site alone.

CHORD Core

Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory

British Columbia

Outrigger station

Green Bank Observatory

West Virginia

ivan semeniuk and john sopinski/the globe and mail photo: Aaron Hemens /

The Globe and MailSource: Juan Mena-Parra, University of Toronto

For centuries, astronomers relied on light to provide information about what goes on in the universe around us – first with the unaided eye and then with telescopes that can magnify and brighten the view.

But the light that human eyes can see is just a sliver of a larger spectrum. At longer wavelengths that are invisible to the eye that spectrum can be probed with radio antennas. And just as a mirror in an optical telescope can collect the light of a faint star or galaxy to make it visible in the eyepiece, a dish antenna can bounce radio waves into a receiver and pick up sources that are far off in space.

CHORD goes one step further and replaces a single large dish with many smaller ones that have the equivalent area of two soccer fields. There are other antenna arrays like this elsewhere in the world. What makes CHORD different is the sheer number of dishes and the fact that they are being made so nearly identical to each other. This makes the performance of the telescope extremely exacting – and ideal for achieving a few key tasks.

One is detecting radio waves emitted by atoms of hydrogen – the simplest and most abundant element in the universe. This can reveal how matter is distributed at the largest scales, and offers a way to track the history of our expanding, accelerating universe.

Long ago, in the aftermath of the Big Bang, the universe was a hot, dense ocean of gas that was booming with acoustic waves – the cosmic version of sound. These days, sound can’t travel in the near-vacuum of space, but while they lasted the acoustic waves left their mark on the way matter is concentrated in the universe. There are peaks where atoms are more plentiful and valleys where there are only empty voids.

As the universe continues to expand, the separation between the peaks grows. This provides cosmologists with a handy metre stick that tracks how the rate of expansion has changed. If CHORD can tease out this information, it will reveal something about how the universe is likely to end up – in particular, whether the expansion will continue to accelerate and go on forever or eventually reverse.

Measuring fast radio bursts from the Earth’s surface is tricky: The Australian array in this illustration, ASKAP, has 36 dishes to trace where a burst comes from. CHORD aims to have 512.Courtesy of Andrew Howells/AFP via Getty Images

CHORD is also designed to be a prolific detector of transient signals that are fleeting but can be equally revealing. They include random blasts called “fast radio bursts” that appear suddenly and are gone a split second later.

When the bursts were discovered in 2007, astronomers were stunned to realize that they originate far outside our Milky Way galaxy. They signify explosive events of mind-numbing energy, and have been linked to a curious class of objects called magnetars.

These are ultradense and highly magnetized objects that form when massive stars explode as supernovas and shed their outer layers. Now, these stellar remnants can produce violent outbursts akin to solar flares but far more powerful.

Since their discovery, astronomers have realized that fast radio bursts can be used to probe where matter is located across intergalactic space. The signal we receive from each burst is like a shaft of sunlight piecing a dust-filled room, briefly exposing the particles that lie along the path.

Over time, astronomers hope to use CHORD to build a picture of how much matter is present in the vast, dark gaps between the galaxies.

“We are going to transform fast radio burst science from one of finding objects and understanding them to using those objects as tools to understand the universe,” Dr. Dobbs said.

When a new dish is ready, workers at the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory transport it to its installation site as part of the CHORD array nearby. Production manager Richard Hellyer and project director Matt Dobbs have hundreds more such installations to get through.

The John A. Galt Telescope, named for one of the B.C. observatory’s first employees, has been here since 1960. CHORD is one of several projects to spring up in its neighbourhood since then.

CHORD is located at the Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, a facility that many Canadians have likely never heard of.

Opened in 1960 by the National Research Council of Canada, the observatory’s role includes radio monitoring of the sun, whose electromagnetic burps and hiccups can affect orbiting satellites and communications around the world.

The area’s geography explains why the location was chosen. Here, the landscape resembles a baseball glove: Stubby mountains surround a smooth pocket of ground open wide to the sky. The mountains help to screen the valley from local radio transmissions, so that astronomers can concentrate on catching signals from deep space.

Late last year I visited the site to get a sense of how CHORD is taking shape and to speak with key members of the project team, who had gathered there for a group meeting. (Normally they are based in separate locations, at universities and institutes across Canada.)

We started off around a large table in the “Locke room” – named after John L. Locke, a Canadian astrophysicist who was the first head of the observatory. It looks like any other meeting room until you notice the copper-coloured mesh across the windows. Indeed, the entire space is encased in metal, with aluminum panels in the walls, floor and ceiling. These keep radio waves from leaking out and interfering with the observations under way outside.

It’s serious business. With all the sensitive receivers around, even switching on a hand-held recorder – not to mention a cellphone – is like shouting in a quiet library. But when I was caged in the Locke room with the CHORD team, my gear was not a problem.

Outside the observatory, weather-resistant coverings keep the dishes safe from the elements. Inside, there are safeguards to keep stray radio waves from contaminating experiments.

Our conversation soon turned to how CHORD will achieve its aims while living within its means.

“Canada put tremendous faith in us,” Dr. Dobbs said. “The funding we have to build this on Canadian soil is unprecedented, but it’s a fixed budget.”

Not long after CHORD was approved for funding in 2021, the team learned what that meant. As steel prices soared during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, they realized that their telescope would be dead in the water unless they completely redesigned the radio dishes in order to minimize metal parts.

CHORD’s designers took a lesson from the boat-building industry: Small powerboats and canoes are often made of fibreglass in a highly repeatable fashion to drive down manufacturing costs. This was the strategy the CHORD team adopted, making the dishes on site using moulds to shape the lightweight material.

The question was whether they could crank out dishes with the precision and repeatability needed for a radio astronomy array. It turned out they could.

The crew undertaking the work mainly consists of people living in the Okanagan region who a year ago could not have imagined that they would be doing such tasks, not to mention paving the way to new discoveries in the cosmos. Now they form the heart of what could be the most specialized assembly line in the country.

“How Canadian is that,” Dr. Dobbs said. “These guys have made beautiful moulds that could build canoes, and instead they’re building these perfectly precise dishes.”

To find the right materials at a time when steel is costlier, engineers turned to boat-building for inspiration.

Later on in my visit, when walking around the dishes already in place, it was easy to see other ways that costs have been minimized. For example, the dishes cannot be steered on command to different targets of interest on the sky. Each one only swivels along the north-south line and is essentially aimed by hand with the help of a motorized tool.

None of that impedes the science goals of CHORD. Once the dishes are pointed in the same direction, the sky rolls overhead as Earth rotates. CHORD then looks at everything within its field of view. The hard part is managing the vast river of data that results and picking out only the signals that matter. Without that selection process, the instrument would quickly succumb to information overload.

CHORD manages this challenge using 156 graphics processing units (GPUs) – the kind of computer chips used in video games. Armed with custom software developed by the project team, CHORD has the number-crunching power to zero in on the signals that matter.

“This is a machine for turning astrophysics problems into computer science problems,” Dr. Smith said.

Maura McLaughlin, a radio astronomer at West Virginia University who is not a member of CHORD, said the project is a “pathfinder for a new way of building telescopes,” in which the main investment is not in physical structure but in digital infrastructure – the chips and electronics that make it work.

“It’s really smart because that stuff is only going to get cheaper,” she said. “Five years from now if CHORD wants to like double itself, it can probably do that for a fraction of the cost that it took to build the original CHORD.”

The idea for CHORD grew out of an even simpler and remarkably successful project called CHIME (the Canadian Hydrogen Intensity Mapping Experiment) that is still operating alongside the spot where CHORD’s multiple dishes are being installed.

CHIME uses no dishes at all. Instead, four parabolic metal troughs, each 100 metres long, collect radio waves from directly overhead and reflect them into receivers. The voluminous view is essentially a line that sweeps across the turning sky, like running the entire universe through a scanner once a day.

The approach has proven highly efficient when it comes to spotting fast radio bursts. To date, CHIME has found about 90 per cent of all the ones ever discovered. Mostly importantly, it demonstrates the cost effectiveness of an instrument that collects a huge amount of data and then relies on sophisticated computation to make discoveries.

CHIME was the first to find bursts from this galaxy – one similar to our Milky Way – but it took an international team to locate it.NSF’s Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory/Gemini Observatory/AURA

However, CHIME’s view of the sky is not sharp enough to precisely locate the phenomena it sees. This has set the stage for CHORD.

Because it uses dishes, CHORD’s view of the sky is not a line but a two-dimensional spot. Projected on the sky, the spot is two to 10 times the width of the full moon, depending on which wavelength is used. The choice means that CHORD sees less sky than CHIME at any given moment, but its larger surface area gives it more sensitivity to faint sources. Over time, as its dishes are positioned at different angles, it will explore a much larger volume of the universe.

CHORD also detects radio waves across a wider range of frequencies, which translates into seeing hydrogen at different distances. At its most extreme, CHORD could detect radio waves coming from more than 10 billion light years away.

This impressive span means that CHORD will have a better chance of turning its hydrogen map into a measure of how the expansion of the universe has changed over time – something that CHIME has not yet been able to achieve.

CHORD will map the distribution of hydrogen in space to spot baryonic acoustic oscillations – sound imprints of the early universe. Learn more about how these can be used to track the history of cosmic expansion.

The current cosmological picture suggests that the universe as we know it is the product of a tug of war between too poorly understood phenomena. One is dark matter – a mysterious substance whose gravity acts to slow the expansion of space. The other is dark energy, an even more mysterious property that makes the expansion accelerate. If CHORD can track the expansion with enough accuracy, the results can shed light on the nature of the two opposing effects.

CHORD could also weigh in on a cosmological mystery that has to do with the roughly 5 per cent of the universe’s content that is neither dark matter nor dark energy. It’s the ordinary matter that makes up atoms, stars and people.

The cosmic microwave background is one piece of the puzzle needed to understand matter in the universe, and projects such as CHORD hope to provide others.ESA-Planck Collaboration via Reuters

The quantity of matter in the universe is known from a separate measurement based on the afterglow of the Big Bang, called the cosmic microwave background. The trouble is that when astronomers count up all the galaxies and other ways that matter makes itself visible, the number they get is far too low.

This disparity means there must be more matter than we can see, and a good bet is it can be found in the space between galaxies. By using fast radio bursts to guide the way, CHORD may finally find it.

Key to this work will be the 128 additional dishes located at two remote sites in the United States. Along with the core array in B.C., they will form a large triangle that spans the continent. And just as the core array forms a single large telescope by integrating the signals from all its separate dishes, the two “outrigger” stations will be integrated and reveal the radio universe as sharply as a single dish the size of North America.

“It’s clear that CHORD will be the world’s cutting edge for fast radio bursts,” Dr. Dobbs said. If it is equally successful at mapping the hydrogen across the universe “it could transform the field.”

At the dish-making facility, Richard Hellyer and his team know speed is of the essence in getting CHORD ready for new discoveries. But they must rigorously test each dish to make sure it’s fit for purpose.

I finished my visit in the large temporary building – about the size of two hockey arenas – that serves as CHORD’s production facility. Here, radio dishes are made, measured and precisely finished.

“This is where the craftsmanship comes into play,” said Richard Hellyer, a long-time member of the observatory and production manager for the project.

“Currently we could lay up a dish, complete the assembly and have it out the door to the array in four days,” he added. By the time the production is at full tempo with parallel teams, “our target is to do two antennas out the door every workday.”

CHORD has made the observatory a busy place, perhaps busier than any other time in its history. According to Brian Hoff, who is managing the project installation for the National Research Council, excitement about the growing array of dishes and what they might achieve is running high.

“There seems to be a particular harmony between CHORD construction and observatory operations,” he said.

Before the new year, members of the CHORD team put their system through its first operational test. A trio of dishes was used to observe Cassiopeia A, a glowing wreath of gas expelled by a supernova that is a strong source of radio emission. The result was a graph showing CHORD’s “first fringes.” It demonstrates that the output from the dishes were correctly combined to produce a wavy interference pattern – a key milestone on the way to linking all the dishes into one receiver.

The milestone prompted a celebratory cake at the observatory, featuring a replica of the fringes in icing.

The CHORD team celebrated their test of radio signals from Cassiopeia A by inscribing the readings on a cake.Supplied

“It’s a very different way of doing astronomy in Canada,” said Dr. Dobbs, speaking about the broader impact of creating a new kind of instrument entirely from scratch.

Mostly, Canada buys into big science projects in a supporting role in exchange for data and participation. With CHORD, the project is its own separate universe of problems to solve and experience to gain.

In a couple of years the science rewards should be apparent. The boost to Canada’s research community may last far longer.

Space is the place: More from The Globe and MailIvan Semeniuk reports

NASA’s Pandora sets out to deduce what exoplanets are really like

UBC team delves into deep space to see how galaxies form

Neutrino results offer possible clue as to why matter exists

Video: Jeremy Hansen is moonward bound

Soon, the Artemis II mission will send Canadian Jeremy Hansen around the moon. He explains what he and other astronauts hope to accomplish there that robots cannot.