Mars may be dry and dusty but it certainly isn’t boring. While it may not be as geologically active as our beautifully blue-green planet, its remarkable red surface has constantly been reshaped by various forces.

A recent press release from the German Aerospace Center (DLR) presents a new set of images that show how even a relatively small swathe of landscape is sculpted by numerous competing natural forces, including volcanoes, asteroids, and the “raw power of the wind over vast periods of time.”

Fortunately, Mars’ geologically sleepy nature preserves the landscapes that chronicle the red planet’s dynamic history.

Eons of Planetary History Locked in a Landscape

These recently released snapshots come from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Mars Express orbiter and its High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) instrument, which was developed by DLR and has been in operation since 2004. Recently, Mars Express has revealed a variety of Martian planetary phenomena, including an atmospheric “butterfly” and a 1,600-kilometer labyrinth of ancient channels carved by floods.

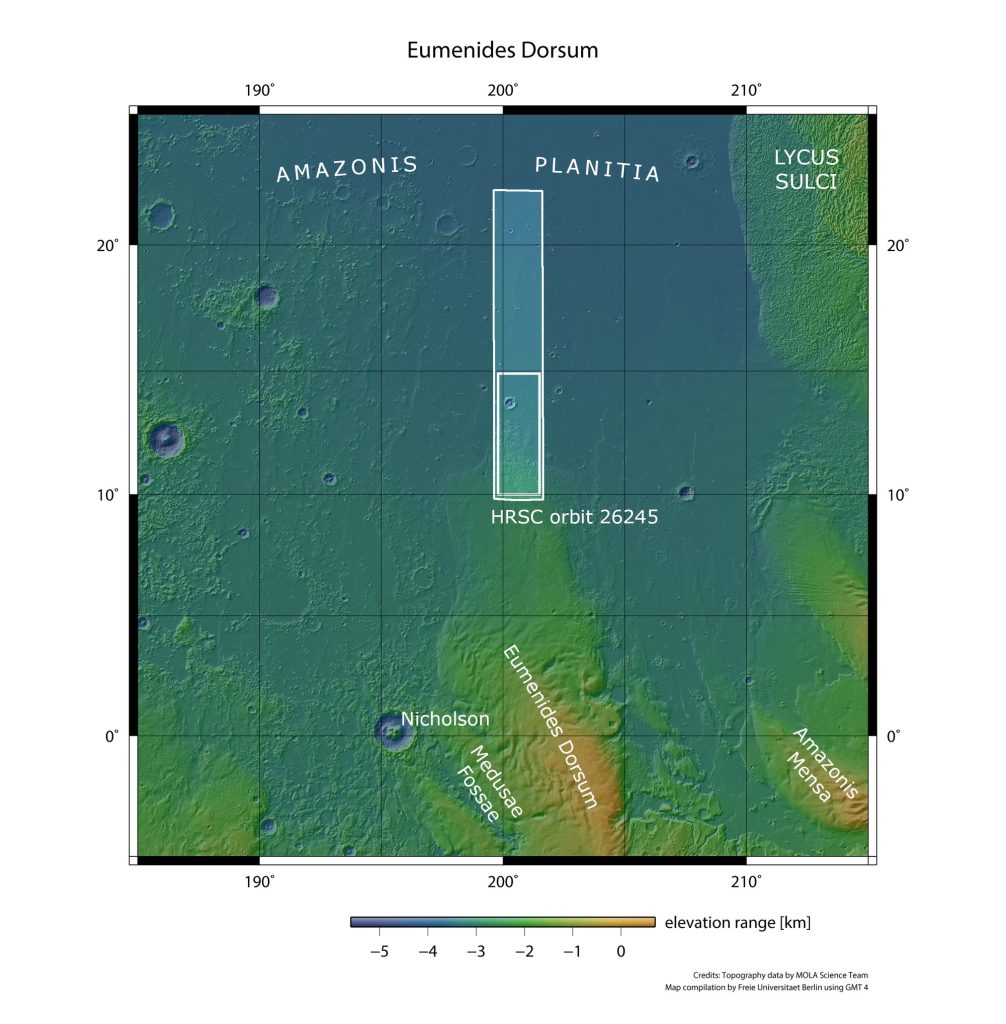

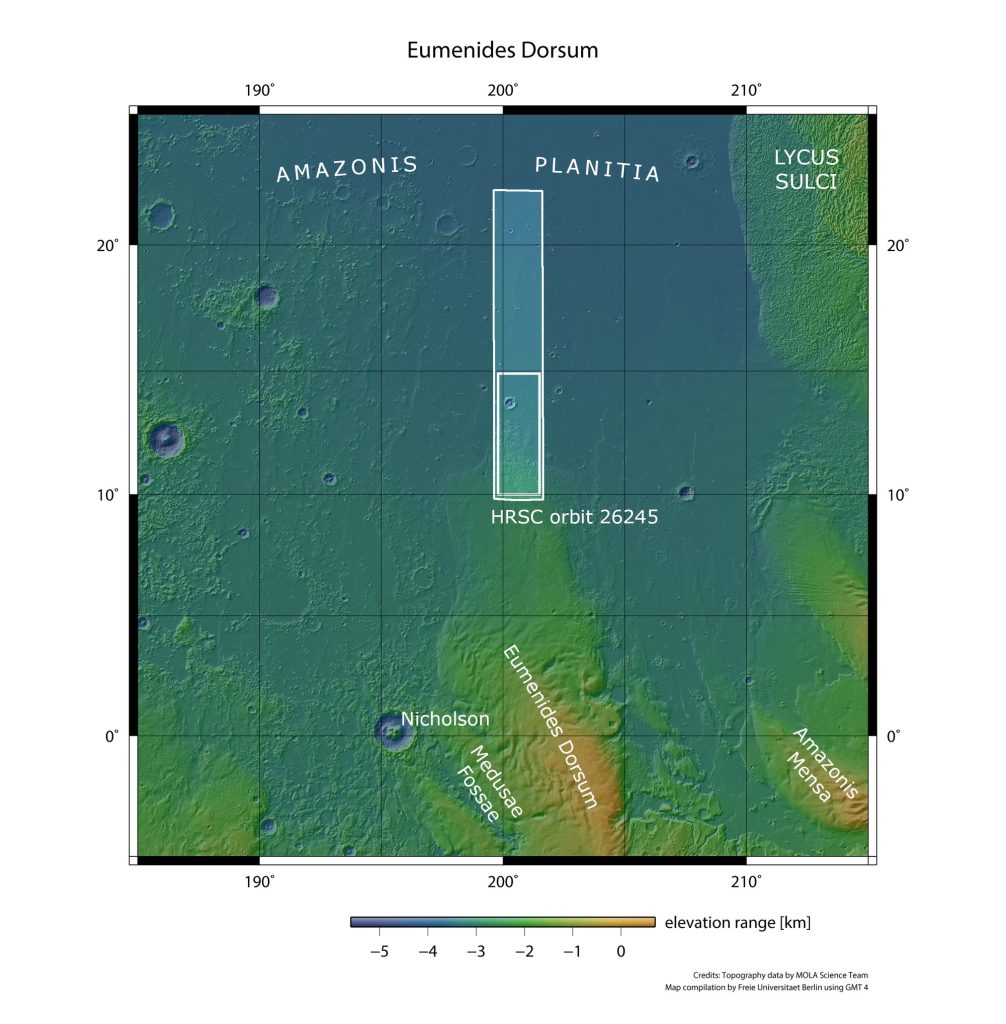

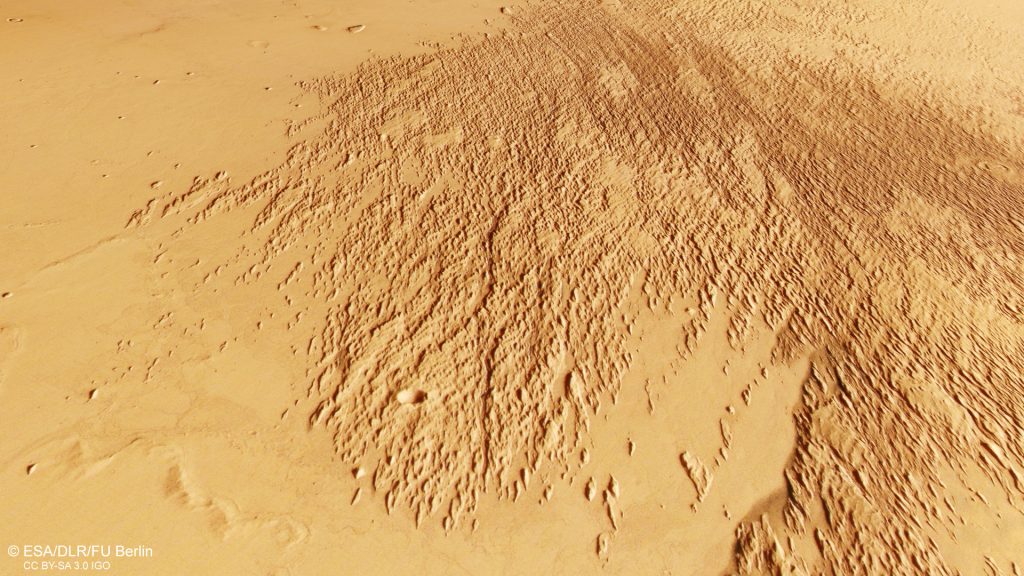

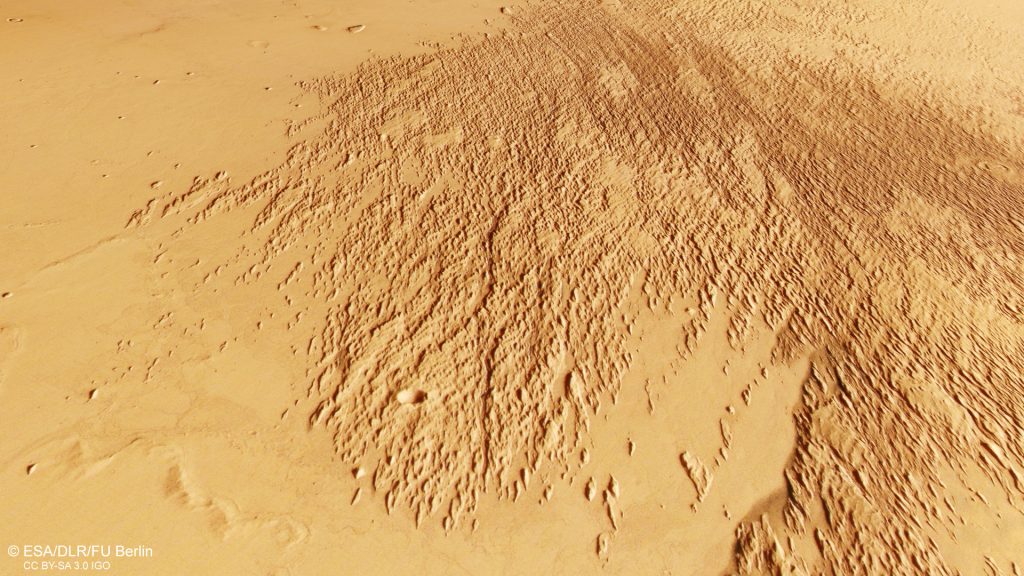

Mars suffers no shortage of spectacular features, as is apparent on the timeless terrains of Amazonis Planitia, a 2-million-square-kilometer lowland plain named after the famous Amazon warriors of Greek fame.

Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

As per the inset above, the primary featured image covers around 28,000 square kilometers, an expanse almost as large as Belgium. It is situated north of the Martian equator and west of Olympus Mons, the solar system’s largest (extinct) volcano.

Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

Credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin

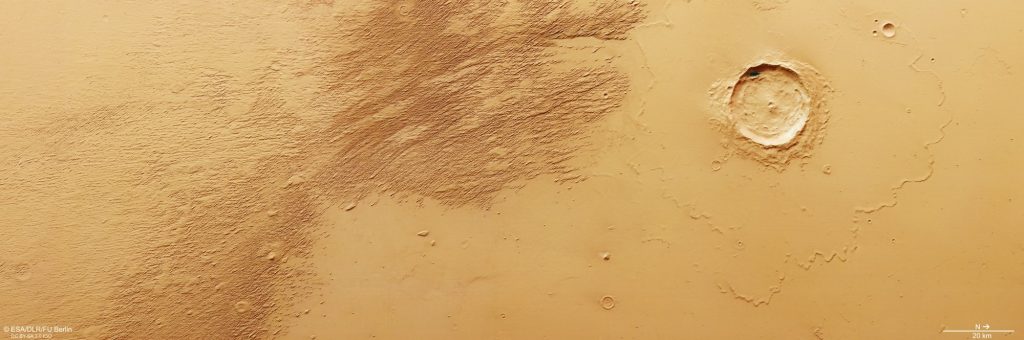

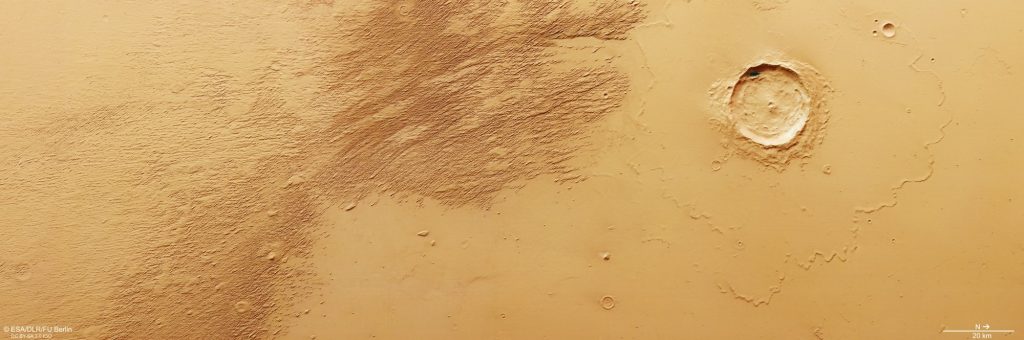

Its most immediately striking detail is a prominent impact crater that spans 20 kilometers (12.4 miles) in diameter and 1,200 meters (nearly 4,000 feet) in depth.

To the left and bottom of the crater we see “platy flows,” the remnants of a magnificent but long-gone sight: a living Olympus Mons. These platy flows may resemble ice sheets, but they likely formed from Olympus Mons’ oozing lava, which solidified while the magma beneath it still flowed, fracturing the solidified lava crust to give it a plate-like appearance.

The darker, rougher patches stretching from the top of the image are “yardangs,” products of slow-acting but abrasive Martian winds blowing persistently from the same direction. As winds carry sand and other loose bits of the Martian regolith, they sandblast the softer surfaces, like sedimentary rocks. Since “the broader end [of the yardangs] always faces into the wind, while the narrower end points downwind,” astronomers can deduce that the winds here have blown from southeast to northwest.

Credit: ESA/DLR/FU BerlinRevealing Mysteries with Martian Forensics

Credit: ESA/DLR/FU BerlinRevealing Mysteries with Martian Forensics

These diverse features allow astronomers to conduct planetary forensics and form a chronology of their occurrence. The lava flows occurred first, since the yardangs lie on top of them. So volcanism shaped the landscape before it was intensely reshaped by wind.

The crater formed last, based on the position of the yardangs and the observation that impact ejecta from the crater covers the lava field. Smaller, smoothed, rounded craters can be seen in the southeast of the image, though their heavy erosion suggests that they are significantly older than the large star-of-the-show crater. Interestingly, the smaller craters are round because the impact compacted the strike zone, compressing the surface materials into a tougher substance that resisted the slow but unceasing march of Martian winds.

However, one sizable mystery remains. Researchers still cannot precisely explain why Mars’ southern highlands are several kilometers higher than the lowlands to the north of the equator. But, then again, astronomy wouldn’t be any fun without riddles to unravel.