Modern astronomy no longer advances by simply building bigger telescopes. It advances by solving control problems at extreme scales where mirrors behave like flexible structures, light arrives already distorted by Earth’s atmosphere, and nanometer-level errors determine whether an image is usable at all.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, scientific breakthroughs in astronomy, cosmology, and astrophysics have become commonplace. Thanks to improvements in instruments, engineering, and data analysis, scientists can see farther and learn more about our Universe than ever before.

Examples include the thousands of extrasolar planets discovered since 2007, the 2015 discovery of gravitational waves, and the exploration of the “Cosmic Dark Ages” by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), starting in 2022.

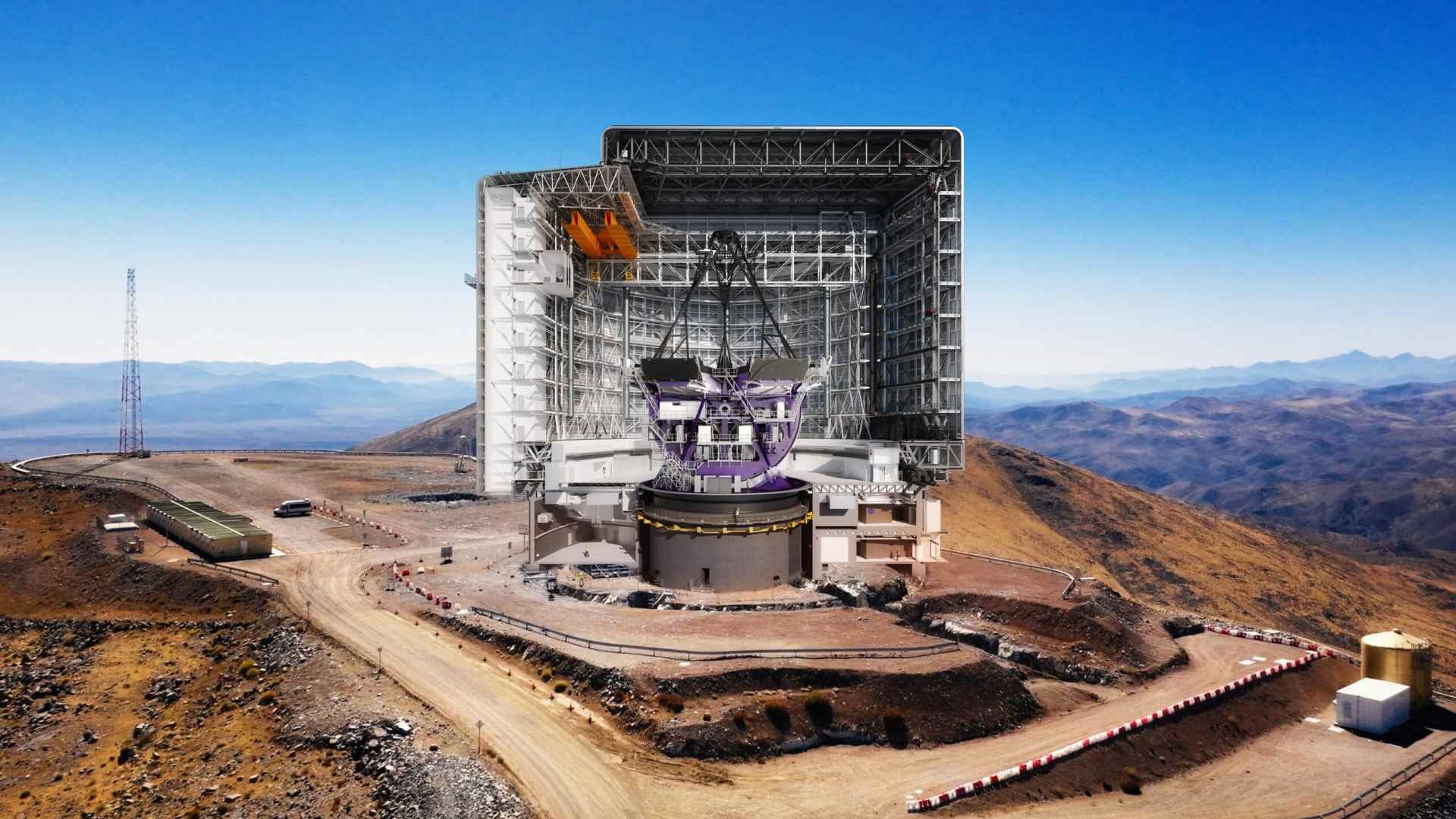

Scientists expect to learn even more as next-generation telescopes (ground-based and space-based) become operational. Beyond Webb, SPHEREx, and the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Euclid space telescope, there’s a new class of “extremely large telescopes” currently under construction. This includes the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), under construction in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile.

The GMT is overseen by an international consortium consisting of leading research institutions from the US, Chile, Australia, Brazil, Israel, South Korea, and Taiwan. The GMT collaboration broke ground on the new telescope in 2015, and it is expected to be operational by the early 2030s. The GMT will be used to study a wide range of astrophysical phenomena, including the habitable exoplanets and the cosmic origins of chemical elements.

Nighttime exterior telescope rendering with support site buildings in the foreground. Credit: Giant Magellan Telescope – GMTO Corporation

Nighttime exterior telescope rendering with support site buildings in the foreground. Credit: Giant Magellan Telescope – GMTO Corporation

Mirror design

Aside from the GMT, other examples of this new class of telescope include the European Southern Observatory’s (ESO) Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) in Chile and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) in Hawai’i. Extremely large telescopes are so-named because they feature massive primary mirrors and apertures of 65.5 to 328 ft (20 to 100 meters).

This is nearly four times as large as today’s largest telescopes, and provides up to 200 times the resolution and imaging capability. This leap in observing capability will revolutionize astronomy, enabling the study of everything from planets and galaxies to Dark Matter (DM) and Dark Energy (DE). At the heart of this observatory is the segmented mirror design.

The GMT will feature seven of the world’s largest mirrors, each measuring 83.33 feet (25.4 m) in diameter, for an overall light-collecting area of 3,960 square feet (368 m2). Each mirror measures about 27.5 feet (8.4 m) in diameter and is composed of about 17.64 short tons (16 metric tons) of Ohara E6 low-expansion glass.

Its observations will cover the optical and mid-infrared wavelengths, spanning 320 to 25,000 nanometers (nm). While this is not the same infrared-observing capabilities as space-based telescopes, the GMT is expected to have a resolving power approximately 10 times that of the Hubble Space Telescope and 4 times that of the JWST.

Along with the ELT and TMT, the GMT will combine a large primary mirror with adaptive optics (AOs), and sophisticated spectrographs to gather light, enabling direct imaging studies of exoplanets, the study of distant stars and galaxies, and the identification of chemical elements in the early Universe.

The GMT is a Gregorian telescope, a type of reflecting telescope that uses two concave mirrors. This includes the primary concave paraboloid mirror, which collects and focuses light. Then, there’s the secondary concave ellipsoid mirror, which reflects light back through a hole in the center of the primary. The light is then directed out the bottom end of the instrument, where it is analyzed by the telescope’s instruments.

One of the main advantages of this design is its short focal length, which results in a compact focal plane and brings light into focus extremely quickly. This allows for science instruments that are up to 27 times smaller in volume than those of other extremely large telescopes, without compromising performance. Once complete, the GMT will be the largest and most sophisticated Gregorian telescope ever built.

As Rebecca Bernstein, the GMT’s Chief Scientist, told IE via email:

Telescope performance depends equally on how much light a telescope collects and how well it can use that light. The optical system of the Giant Magellan Telescope is designed to deliver the highest-performing combination of collecting power, image resolution, and field of view, resulting in the highest performance across a wide range of science.

The design also enables the development and use of state-of-the-art cameras and spectrographs that analyze light more efficiently, with higher spectral and spatial resolution, all while remaining more compact, lower risk, and more cost-effective than those on any other extremely large telescope design.

However, the segmented mirror design also presents an additional challenge. Between each mirror segment, there are gaps measuring approximately 13.6 inches (34.5 cm) in diameter. These gaps could lead to wavefront inconsistencies known as “peddle modes” and make it challenging for the telescope to maintain proper phasing, or the ability of each mirror to collect light and combine it correctly without introducing errors.

Adaptive optics

To break it down, all telescopes suffer from the same issue: atmospheric turbulence, which distorts starlight. AOs counteract this by using deformable mirrors that can adjust their reflective surfaces to compensate for atmospheric interference. While many ground-based telescopes today have been retrofitted with AO, the GMT is one of the first to incorporate state-of-the-art AO into its core design.

The GMT accomplishes this through an AO architecture comprising two main elements. First, there’s the Natural Guide Star Wavefront Sensor (NGWS) developed by the GMT collaboration and the Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica (INAF) in Italy. This unique wavefront sensor can simultaneously measure both rapidly changing optical aberrations from atmospheric turbulence and mirror segment position (phase) errors.

Richard Demers, the Wavefront Sensing and Control Manager, explained to IE via email: “This Natural Guide Star Wavefront Sensor (NGWS) combines a pyramid wavefront sensor to accurately measure the rapidly changing atmospheric aberrations and a first-of-its-kind holographic dispersed fringe sensor to measure the mirror segment phase errors. The signals from the two wavefront sensors are combined to calculate the commands needed to control both the rigid body positions of the mirror segments and the mirror shapes. The NGWS is thus responsible for both phasing the segmented telescope and correcting static and dynamic optical aberrations.“

Second, there are the seven adaptive secondary mirrors, each positioned above one of the primary mirrors’ light paths. They are composed of Zerodur, a specialized lithium-aluminosilicate glass-ceramic material. This technology will reportedly enable the GMT to produce images 4 to 16 times sharper than those from the JWST.

Cross sectional rendering of the Giant Magellan Telescope enclosure and mount at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. Credit: IDOM/GMTO

Cross sectional rendering of the Giant Magellan Telescope enclosure and mount at Las Campanas Observatory in Chile. Credit: IDOM/GMTO

Each secondary mirror measures roughly 3.45 feet (1.05 m) in diameter and is just 0.08 inches (2 mm) thick. This allows them to deform their surfaces at 2,000 times per second, collecting distorted light reflections and cleaning thembefore sending the concentrated light to the telescope’s instruments. Adjusting their shape comes down to 675 magnets bonded to the back of each mirror, which are pushed or pulled by electromagnetic actuators. Demers summarized:

“The adaptive optics system is the keystone for achieving high image quality in an extremely large telescope (ELT). The operational challenge of a large, segmented-aperture telescope like the Giant Magellan Telescope is to position or “phase” the mirror segments as if they were part of a large monolithic mirror.

The Giant Magellan Telescope uniquely approaches this challenge by integrating its adaptive optic system directly into the telescope rather than placing it as an add-on downstream from the telescope focus. We achieve this by making the telescope’s secondary mirror the key adaptive optics mechanism.”

Where does GAPS come in?

The GMT’s AO architecture relies on cutting-edge compute and optical sensing and control technology to acquire extremely high-resolution images using natural guide stars. This technology merges optical system designs, real-time control mechanisms, and computational algorithms. The GAPS testbed was assembled to validate the technology for this process in preparation for the NSF’s Final Design Review.

GAPS relies on a Holographic Dispersed Fringe Sensor (HDFS) and a Pyramid Wavefront Sensor (PyWFS) to achieve the necessary accuracy in phasing the mirrors. HDFS uses diffraction and interference to encode the differential piston into a measurable signal. When two apertures interfere in the focal plane, they create a fringe pattern. This fringe pattern modulates the individual Point Spread Function (PSF) of each aperture. The phase shift of the fringe pattern is also wavelength dependent.

To demonstrate how the AO system will work, the Giant Magellan Telescope has built the GMT Adaptive Optics & Phasing Sensor (GAPS) testbed. GAPS encompasses a starlight source, a telescope simulator reproducing the precise Giant Magellan Telescope pupil geometry and a full-scale prototype of the NGWS.

The telescope simulator will feed the NGWS prototype with an optical beam identical to that of the real Giant Magellan Telescope. GAPS will be used to demonstrate the required diffraction-limited performance in an environment characteristic of the observatory in Las Campanas, Chile. The GAPS testbed will serve as both a validation tool for the AO design and control strategy as well as a platform for development of the observatory AO algorithm software.

Development of the GMT is progressing on multiple fronts. As of 2025, all seven primary mirrors were cast, two of its Adaptive Secondary Mirrors neared completion, the primary mirror support system was validated, and work proceeded on the telescope mount and the GMT’s four primary instruments: the Large Earth Finder (G-CLEF), the Near-Infrared Spectrograph (GMTNIRS), the Integral Field Spectrograph (GMTIFS), and (already noted) the GAPS.

Once complete, this observatory will deliver cutting-edge images of the Universe, allowing astronomers to investigate some of its deepest mysteries.

As Bernstein described the potential: “The Giant Magellan Telescope will help answer today’s biggest questions, from uncovering the cosmic mysteries of dark matter and dark energy to searching for signs of life on distant planets. Each new generation of telescope reveals questions we have not yet imagined, and the Giant Magellan Telescope is designed to do exactly that: discover the unknown.”