The James Webb Space Telescope has presented astronomy with an awkward puzzle. Looking back into the infant Universe, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, it’s catching sight of black holes that are impossibly, frustratingly massive. They’ve somehow ballooned to millions of times the Sun’s weight when, by all reasonable calculations, they should barely exist yet. For years, astronomers have been scratching their heads: how did these behemoths grow so quickly?

An answer now seems to be emerging from Ireland. Researchers at Maynooth University have run simulations of the early cosmos at a level of detail that’s never been achieved before, and what they’ve found overturns a longstanding assumption about black hole origins. The culprit behind the mystery isn’t some exotic mechanism that only works under rare circumstances. It’s simply small black holes, born from the Universe’s first stars, doing something we didn’t think they could: gorging on surrounding material at catastrophic rates in the chaos of the primordial Universe.

“We found that the chaotic conditions that existed in the early Universe triggered early, smaller black holes to grow into the super-massive black holes we see later following a feeding frenzy which devoured material all around them,” says Daxal Mehta, a PhD candidate leading the study. The breakthrough matters because it slots a crucial missing piece into our understanding of cosmic history. For decades, astronomers have been stuck between two competing ideas about where massive black holes come from. One camp argues for “light seeds,” black holes perhaps 100 times the Sun’s mass at birth, left behind when the Universe’s first stars collapsed. The other champions “heavy seeds,” exotic objects born somehow already a hundred thousand times heavier. Light seeds seemed too feeble; they appeared they’d never grow fast enough to explain what we see today.

But now Mehta and his team have shown something remarkable using supercomputer simulations of unprecedented precision. “We revealed, using state-of-the-art computer simulations, that the first generation of black holes – those born just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang – grew incredibly fast, into tens of thousands of times the size of our Sun.” The key was resolution. The simulations zoomed in on regions just 0.1 parsecs across (about 20,000 times the Earth-Sun distance) capturing the suffocating density of gas that surrounded the newborn black holes.

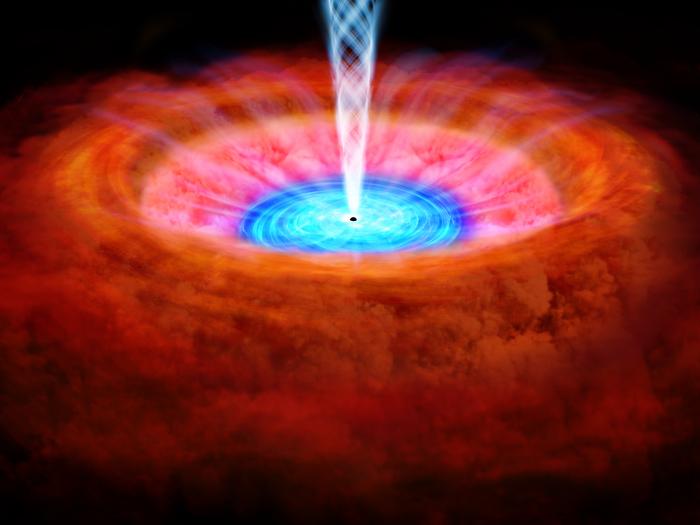

In this cosmic pressure cooker, the physicists’ model reveals a phenomenon known as super-Eddington accretion. That’s a mouthful for something conceptually outrageous: black holes eating material so fast they should blow it all away with radiation. Somehow they don’t. Instead, in the dense clots of gas surrounding these infant black holes, the material piles on faster than light can push it back. One particular black hole in their simulations started at just 66 solar masses and, within a few million years, swelled to nearly 14,000 times the Sun’s weight despite the intense thermal feedback trying to disrupt it.

“This breakthrough unlocks one of astronomy’s big puzzles,” reflects Dr Lewis Prole, a team member. “That being how black holes born in the early Universe, as observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, managed to reach such super-massive sizes so quickly.” The research provides something the field has desperately needed: a credible pathway from the first stellar remnants to the monstrous nuclei now sitting at the hearts of galaxies. More pointedly, it suggests those heavy seeds might not even be necessary. “Heavy seeds are somewhat more exotic and may need rare conditions to form,” explains Dr John Regan, who leads the Maynooth group. “Our simulations show that your ‘garden variety’ stellar mass black holes can grow at extreme rates in the early Universe.”

What makes this work so compelling is its breadth. The simulations didn’t just find one black hole undergoing this frantic growth. They discovered dozens of them, across multiple runs at different resolutions, all showing the same behaviour. Some grew in pristine, metal-free gas untouched by prior stellar generations. Others feasted in regions already seeded with metals from earlier supernovae. The growth was never sedate—it happened in sharp, violent bursts, sometimes lasting barely a million years. But in those bursts, the black holes could sometimes exceed the theoretical Eddington limit by a factor of a thousand.

The implications stretch far beyond settling a historical debate. Regan and colleagues point out that their findings have direct consequences for future observations. The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna—a joint ESA-NASA mission scheduled to launch in 2035—will detect gravitational waves from distant colliding black holes with unprecedented sensitivity. If populations of these rapidly growing early black holes really did exist, they’d produce telltale ripples across spacetime. “Future gravitational wave observations from that mission may be able to detect the mergers of these tiny, early, rapidly growing baby black holes,” Regan notes.

For now, the Maynooth simulations have their limits. The team could only model the first few hundred million years after the Big Bang—not the full cosmic journey that eventually leads to today’s trillion-solar-mass leviathans. But what the simulations reveal in that window is tantalizing. A small fraction of the small black holes that formed from the Universe’s first stars, if they caught the right conditions at the right moment, could experience explosive growth that bootstrapped them toward the intermediate masses found in later cosmological simulations. Those seeds could then continue growing across billions of years until becoming the cosmic monsters we observe today.

“The early Universe is much more chaotic and turbulent than we expected, with a much larger population of massive black holes than we anticipated too,” Regan reflects. It’s a reminder that the Universe’s infancy wasn’t the orderly, sedate place we sometimes imagine. Instead, it was a teeming cosmos of violent collision, intense feedback, and catastrophic growth. Small seeds becoming giants wasn’t magic—it was just chaos at work.

There’s no paywall here

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!