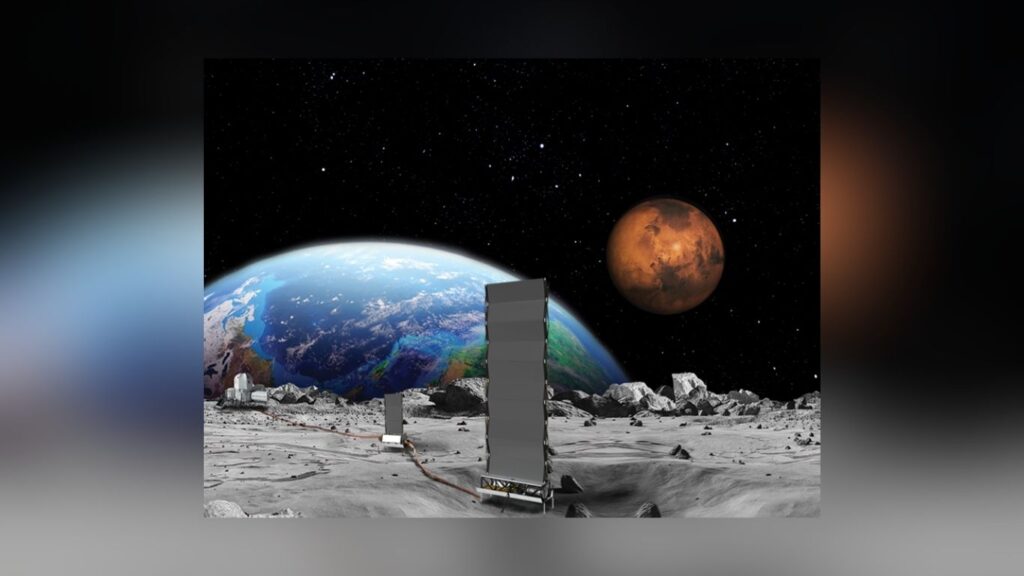

NASA and the U.S. Department of Energy have strengthened their alliance to develop a nuclear fission reactor for the lunar surface, aiming to complete the project by 2030 as part of efforts to sustain long-term Moon missions and advance toward Mars exploration.

The agencies announced the renewed commitment through a memorandum of understanding that supports President Trump’s goals for U.S. dominance in space, including the deployment of nuclear power on the Moon and in orbit.

The initiative draws on more than five decades of joint work in space technology and national security.

“Under President Trump’s national space policy, America is committed to returning to the Moon, building the infrastructure to stay, and making the investments required for the next giant leap to Mars and beyond,” NASA Administrator Jared Isaacman said in a news release.

“Achieving this future requires harnessing nuclear power. This agreement enables closer collaboration between NASA and the Department of Energy to deliver the capabilities necessary to usher in the Golden Age of space exploration and discovery.”

The planned fission surface power system would generate at least 40 kilowatts — enough to supply about 30 households continuously for a decade — offering reliable electricity independent of solar conditions or extreme temperatures. It would operate for years without refueling, supporting NASA’s Artemis program and future endeavors.

“History shows that when American science and innovation come together, from the Manhattan Project to the Apollo Mission, our nation leads the world to reach new frontiers once thought impossible,” Energy Secretary Chris Wright said.

“This agreement continues that legacy. Thanks to President Trump’s leadership and his America First Space Policy, the department is proud to work with NASA and the commercial space industry on what will be one of the greatest technical achievements in the history of nuclear energy and space exploration.”

Developing the reactor poses significant hurdles, including waste heat dissipation in the Moon’s near-vacuum and low-gravity environment, where traditional water-based cooling is impractical.

Potential approaches include solid-state conduction or liquid-metal systems, but both introduce design complexities.

Additional challenges include protecting against abrasive, electrostatically charged lunar dust that clings to equipment, ensuring robust radiation shielding for nearby astronauts, and minimizing the need for repairs in a remote setting.

The initial design phase is finished, but advancing to testable hardware on Earth and eventual flight-ready status will proceed deliberately, influenced by engineering demands, regulatory requirements, and funding constraints. No specific deployment date has been set.

The partnership, highlighted by a January 8 meeting between Isaacman and Wright at Energy Department headquarters, positions the U.S. to lead in space commerce and innovation.