Credit: 2023–2025 CERN. Image credits: Maximilien Brice.

Credit: 2023–2025 CERN. Image credits: Maximilien Brice.

Trapping antimatter is kind of like trying to catch snowflakes with a frying pan — if the snowflakes wanted to blow up the pan every time they touched it. That’s basically the daily grind for CERN physicists who study antihydrogen. For years, they’ve been capturing these fragile anti-atoms one by one, inching toward answers about one of the universe’s biggest mysteries.

Now, they’ve made a major leap.

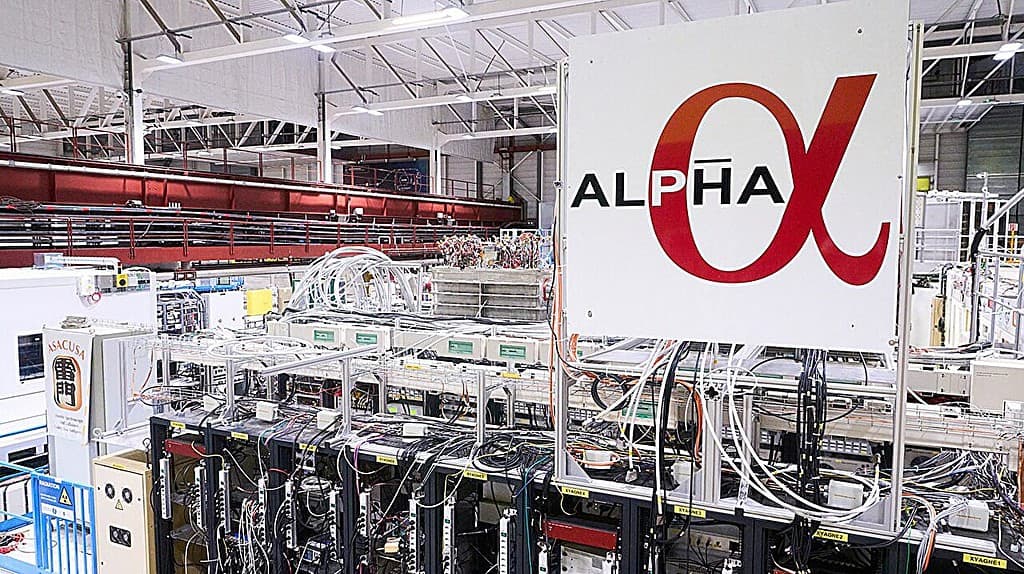

The ALPHA collaboration at CERN has trapped more than 15,000 antihydrogen atoms at once, smashing their previous record. To accomplish this, they used a clever cooling method that uses laser-chilled beryllium ions to siphon heat away from positrons before they combine with antiprotons. The result is a stable, frigid “bucket” of antimatter big enough to turbocharge studies that used to take months.

“These numbers would have been considered science fiction 10 years ago,” said Jeffrey Hangst, spokesperson for the ALPHA experiment. “With larger numbers of antihydrogen atoms now more readily available, we can investigate atomic antimatter in greater detail and at a faster pace than before.”

Bizarro World

Antimatter is, in most ways, the opposite of matter. It’s made of “antiparticles” which have the same mass as their “regular” matter particles, but opposite electric charge. For example, a positron is the antiparticle of an electron. An antiproton is the antiparticle of a proton.

As silly as that may sound, antimatter is one of the biggest mysteries in the universe. According to our current understanding of the Big Bang, the universe should have been created with equal parts matter and antimatter. But look around. Everything (your coffee, your cat, this screen) is made of matter. Where’s the antimatter?

AI depiction of antimatter atom.

AI depiction of antimatter atom.

It gets even weirder. When matter and antimatter come into contact, they annihilate each other and release a large amount of energy. So, it’s not like it could be hiding somewhere surrounded by matter.

Some antimatter particles are relatively common and even created by our bodies in small amounts, but researchers are desperately trying to understand why the universe is lacking antimatter, so they’re recreating the simplest antimatter atoms: hydrogen.

A regular hydrogen atom consists of a proton and an electron. An antihydrogen atom consists of an antiproton and a positron. Since 2010, we’ve been able to trap antihydrogen, but it’s an excruciatingly slow process. You make it, you trap it, and usually, you only hold onto a handful of atoms. In 2018, it took the team ten weeks to accumulate 16,000 trapped atoms for a specific experiment. With this new method, they can get that same amount of data in a single day.

The Big Chill

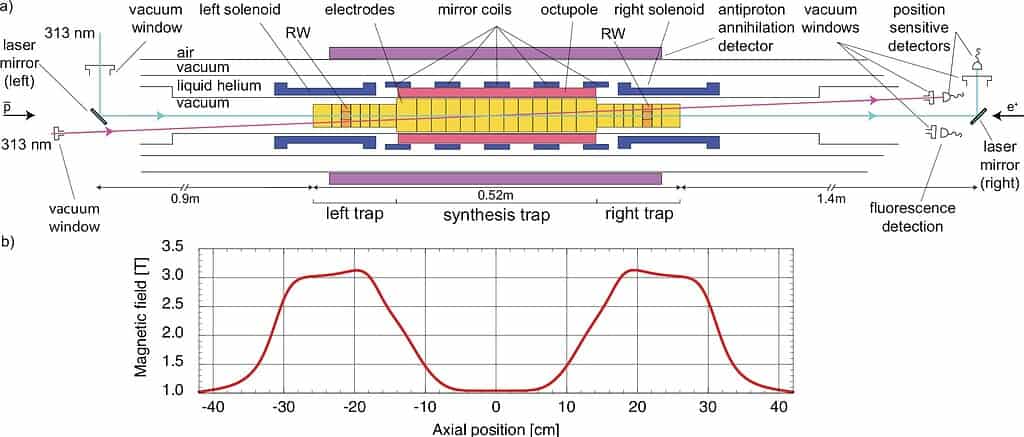

Scientists mix plasmas of antiprotons and positrons in a magnetic bottle called a Penning-Malmberg trap. When these particles combine, they form antihydrogen. But if the ingredients are too hot, the resulting anti-atoms are too energetic. They simply fly out of the magnetic trap and annihilate on the walls before they can be studied.

The secret to this new bounty is temperature. To trap antihydrogen, researchers made it incredibly cold.

First, the researchers collect positrons from a radioactive form of sodium in a magnetic bottle called a Penning-Malmberg trap. But the positrons don’t stay still; they continuously lose energy. Positrons are light and skittish, and they heat up easily. In the past, ALPHA relied on evaporative cooling — basically letting the hottest particles escape to cool the rest. But that limits how cold you can get.

So, the team used ultracooled Beryllium ions. They blasted these atoms with lasers to cool them down. As unusual as it sounds, this technique is now often used to cool down atoms. The lasers interact with atoms and slow down their motion, which essentially reduces their temperature.

When the ultracooled Beryllium atoms collide with the positron plasma, they absorb the heat, leaving the positrons much cooler than before. Suddenly, the magnetic trap wasn’t leaky anymore, and they could capture far more antimatter.

“This result was the culmination of many years of hard work. The first successful attempt instantly improved the previous method by a factor of two, giving us 36 antihydrogen atoms — my new favorite number!” says Maria Gonçalves, a leading Ph.D. student on the project. “It was a very exciting project to be a part of, and I’m looking forward to seeing what pioneering measurements this technique has made possible.”

Everything For Statistics

This isn’t about maxxing the antimatter high score. In the world of particle physics, statistics are everything. You need many data points to rule out potential errors or anomalies and figure out what’s actually happening.

This new production method accelerates antimatter research. Experiments that used to take months can now be conducted in a single day, says Dr. Kurt Thompson, a leading researcher on the project.

Professor Niels Madsen from Swansea University, Deputy Spokesperson for ALPHA has been working on this for years.

“It’s more than a decade since I first realized that this was the way forward, so it’s incredibly gratifying to see the spectacular outcome that will lead to many new exciting measurements on antihydrogen.”

If this stash of antimatter reveals even the slightest difference between hydrogen and antihydrogen (a frequency shift, a gravitational quirk), it could break the Standard Model of physics. It could explain why we are here, and why the universe isn’t just an empty void of radiation; or why matter “won” over antimatter. It could help us understand the very fabric of the universe.

Journal Reference: R. Akbari et al, Be+ assisted, simultaneous confinement of more than 15000 antihydrogen atoms, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-65085-4