A surprisingly ravenous black hole from the dawn of the universe is breaking two big rules: It’s not only exceeding the “speed limit” of black hole growth but also generating extreme X-ray and radio wave emissions — two features that are not predicted to coexist.

The object — a quasar known as ID830 — is an extremely bright and active supermassive black hole (SMBH) that is shooting immense jets of radiation from its poles. It is also emitting intense X-ray emissions, generated by infalling material that swirls around its dark maw at nearly the speed of light.

You may like

Even black holes have limits

Black holes are the universe’s most voracious eaters, but even monsters have a feeding limit. As they attract gas and dust, this material accumulates in a swirling accretion disk. Gravity pulls the material from the disk into the black hole, but the infalling material generates radiation pressure that pushes outward and prevents more stuff from falling in. As a result, black holes are muzzled by a self-regulating process called the Eddington limit.

An artist’s rendition of a black hole, along with its swirling accretion disk, bright corona and jet. (Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI))

Yet black holes can temporarily bypass this limit and undergo rapid growth spurts at a super-Eddington limit. Researchers propose multiple mechanisms for this cosmic gluttony. For example, “it should be perfectly possible for a black hole to consume matter faster than the Eddington limit for a short period of time before radiation pressure builds up to limit the accretion rate,” Anthony Taylor, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin who was not involved in the study, told Live Science via email.

Alternatively, a black hole can consume matter from a disk around its equator while outward radiation pressure expels material from its poles. “In this situation, the radiation pressure would not directly oppose the inflow of matter, thus allowing the Eddington limit to be exceeded,” Taylor added. “There are a variety of geometries where this could work!”

Super-Eddington mechanics may help reconcile SMBH growth models with an expanding catalog of early-universe observations. With its exceptional infrared sensitivity, the James Webb Space Telescope has revealed that SMBHs grew surprisingly fast and surprisingly early, defying all expectations.

So, how did SMBHs get so fat, so fast? Some scientists suggest that Population III stars, the first and largest stars in cosmic history, collapsed to produce black hole “seeds” of 1,000 or more solar masses.

But even these hefty seeds would need to feed at the Eddington limit for more than 650 million years to reach some of their observed sizes. This feat may seem infeasible for several reasons, including the prodigious amounts of gas required to sustain such prolonged gorging.

You may like

Supercharging black hole growth

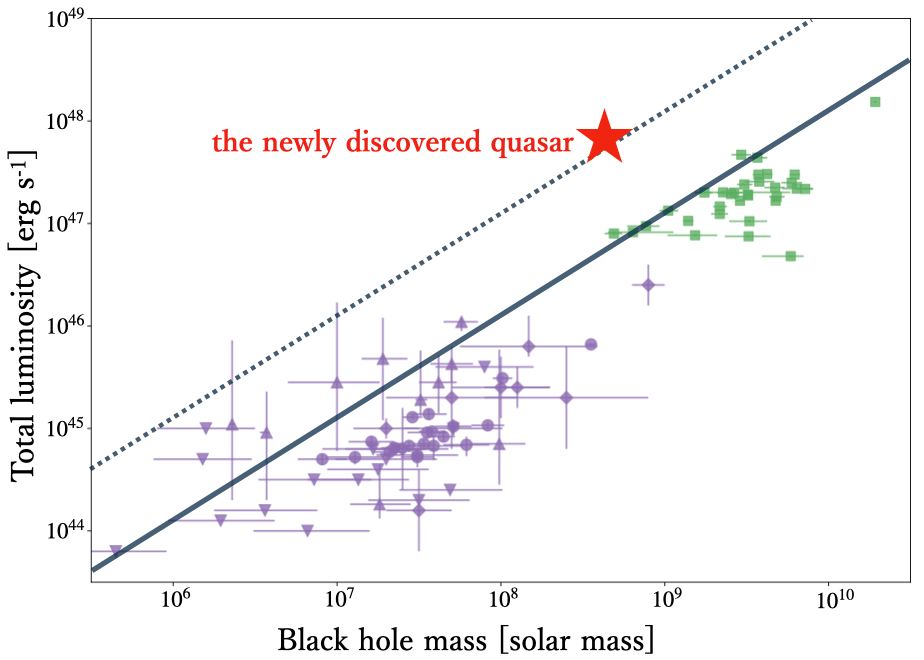

The researchers calculated ID830’s growth rate by measuring its brightness in ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray wavelengths. Its X-ray brightness suggests that ID830 is accreting mass at about 13 times the Eddington limit, due to a sudden burst of inflowing gas that may have occurred as ID830 shredded and engulfed a celestial body that wandered too close.

A graph displaying ID830’s uniquely brilliant luminosity, compared to previously observed objects. The solid line shows the Eddington limit, while the dotted line indicates a black hole feeding rate 10 times above the Eddington limit. (Image credit: NAOJ)

“For a SMBH as massive as ID830, this would require not a normal (main-sequence) star, but a more massive giant star or a huge gas cloud,” study co-author Sakiko Obuchi, an observational astronomer at Waseda University in Tokyo, told Live Science via email. Such super-Eddington phases may be incredibly brief, as “this transitional phase is expected to last for roughly 300 years,” Obuchi added.

ID830 also simultaneously displays radio and X-ray emissions. These two features are not expected to coexist, especially because super-Eddington accretion is thought to suppress such emissions. “This unexpected combination hints at physical mechanisms not yet fully captured by current models of extreme accretion and jet launching,” the researchers said in a statement.

So while ID830 is launching massive radio jets, its X-ray emissions appear to originate from a structure called a corona, produced as intense magnetic fields from the accretion disk create a thin but turbulent billion-degree cloud of turbocharged particles. These particles orbit the black hole at nearly the speed of light, in what NASA calls “one of the most extreme physical environments in the universe.”

A framework for early galaxy evolution

Altogether, ID830’s rule-breaking behaviors suggest that it is in a rare transitional phase of excessive consumption — and excretion. This incredible feeding burst has energized both its jets and its corona, making ID830 shine brightly across multiple wavelengths as it spews out excess radiation.

Additionally, based on UV-brightness analysis, quasars like ID830 may be unexpectedly common, the researchers said. Models predict that only around 10% of quasars have spectacular radio jets, but these energetic objects could be significantly more abundant in the early universe than previously suggested.

Most importantly, ID830 also shows how SMBHs can regulate galaxy growth in the early universe. As a black hole gobbles matter at the super-Eddington limit, the energy from its resultant emissions can heat and disperse matter throughout the interstellar medium — the gas between stars — to suppress star formation. As a result, ancient SMBHs like ID830 may have grown massive at the expense of their host galaxies.

IN CONTEXT IN CONTEXT

IN CONTEXT

Brandon Specktor

Space and Physics Editor

“If super-Eddington black holes are more common than we thought, it likely means there are still some big gaps in our understanding of how objects in the early universe took shape. This discovery adds to a growing pile of evidence from the James Webb Space Telescope that shows stars, galaxies, and black holes in the ancient universe looking much bigger and more mature than theory says they should.”

Obuchi, S., Ichikawa, K., Yamada, S., Kawakatu, N., Liu, T., Matsumoto, N., Merloni, A., Takahashi, K., Zaw, I., Chen, X., Hada, K., Igo, Z., Suh, H., & Wolf, J. (2026). Discovery of an X-Ray Luminous Radio-loud Quasar at z = 3.4: A Possible Transitional Super-Eddington Phase. The Astrophysical Journal, 997(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/ae1d6d