Chronicles of space promises: how do Elon Musk’s predictions match up with reality?

Chronicles of space promises: how do Elon Musk’s predictions match up with reality?

One of the latest posts on Elon Musk’s official X account claims that in 10 years on the Moon and in 20+ years on Mars, humanity will build fully-fledged autonomous cities. Some people took Musk’s new prediction with cautious optimism, while others were a bit skeptical. UST decided not to align with either camp, but instead analyzed what similar predictions by the head of SpaceX had led to in the past; over the years of its existence, the company has managed to combine a history of almost impossible successes with promises that have deviated from the original deadlines by decades.

Read about them in our personal top list of Musk’s space predictions.

Rocket announcements: Through delays to the stars

Back in 2002, when SpaceX was just a group of enthusiasts in a half-empty hangar, Musk made his first bold prediction to the press. At that time, he stated that the company’s first light rocket, Falcon 1, would take off in November 2003. At that time, the commercial launch market belonged to state-owned giants, and Musk’s promise to develop a rocket from scratch in 15 months seemed nothing more than a bold statement by a newcomer who did not fully understand the complexity of rocket technology.

Well, reality quickly brought these big dreams down to a more rational level. Instead of 2003, the first attempt to launch the rocket happened only in March 2006, but it ended in a crash: just 25 seconds into the flight, the Merlin engine started losing pressure. A fire broke out above the engine, which quickly escalated into a serious blaze. This attempt was followed by two more failures, during which Musk invested his last funds, balancing on the brink of bankruptcy.

Elon Musk at the Falcon 1 launch ceremony, 2003. Source: collectspace.com

Elon Musk at the Falcon 1 launch ceremony, 2003. Source: collectspace.com

Only on September 28, 2008, on its fourth attempt, the Falcon 1 launch vehicle finally reached orbit. It was a historic moment — the first private liquid-fuel rocket was able to achieve what previously only governments and space contractors had been able to do. However, if we look at the raw figures, the delay amounted to almost five years from the initial promise, although falling behind schedule is quite common in the rocket sector.

The main thing was different: Falcon 1 actually reached orbit, paving the way for Musk’s team into deep space. After this success, SpaceX opened the door to multimillion-dollar contracts with NASA, without which the company’s future would have been impossible.

When talking about Elon Musk’s rocket promises, it is worth noting that they almost never meet the announced deadlines. In April 2011, he held a press conference where he announced the start of development of Falcon Heavy, the most powerful rocket in the world at that time, with its debut announced for 2013, although Falcon Heavy did not actually take off until February 2018.

Musk turned this launch into a spectacular show, sending his personal Tesla Roadster electric car with a mannequin toward Mars to the tune of David Bowie’s song “Starman.” It happened five years later than planned, but the effect was so impressive that almost no one remembered the delay.

Something similar happened with the announcements about the super-heavy Starship rocket, which was supposed to become the main vehicle for transporting astronauts to the Moon and Mars. In 2019, standing in front of the shiny steel prototype Starship Mk1 in Boca Chica, Musk said that this spacecraft would make its first orbital flight within six months.

However, the rocket subsequently encountered problems with its Raptor main engines and heat shield design, which meant that Starship’s first successful launch into orbit did not take place until 2024. Six months turned into five years, but despite the huge delay, Starship is now a reality. It flies, it returns, and its first stage, Super Heavy, is successfully captured by Mechazilla’s steel claws.

Orbital and Mars Dragon

Even before the first successful launch of Falcon 1, Musk announced even more ambitious plans to deliver cargo to the International Space Station. He claimed that the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft would be able to dock with the ISS as early as 2008-2009. But docking with the ISS required an incredible level of safety and certification that a young private company could not achieve so quickly.

The following years confirmed the initial skepticism, and Dragon’s development took longer than expected. SpaceX not only had to build the spacecraft, but also had to prove to NASA that its rendezvous algorithms did not pose a collision risk to the orbital station, costing more than $100 billion. Musk, in turn, continued to insist on quick deadlines in every subsequent interview, even though the company’s engineers were systematically falling behind schedule.

The actual docking took place only in May 2012, when Dragon was finally captured by the ISS manipulator, which became a sensation. And here we should also note another important fact: despite being four years behind schedule, SpaceX accomplished its promise faster than any other private aerospace company before it.

First docking of SpaceX Dragon with the ISS, 2012. Source: reddit.com

First docking of SpaceX Dragon with the ISS, 2012. Source: reddit.com

The Dragon case highlighted one important feature of Mr. Musk: the head of SpaceX seems to have learned how to use his predictions as a method of putting pressure on his own team and partners. True, without those unrealistic deadlines, Dragon might have taken ten years to build.

Later in 2016, Musk officially unveiled the Red Dragon project. According to forecasts, SpaceX was supposed to send a modified Dragon spacecraft to the Red Planet in 2018 to test the technology for landing heavy objects. This was supposed to be a prelude to manned missions to Mars, which Musk predicted would happen in the mid-2020s. And indeed, the company’s series of rapid successes at that time planted the idea in many people’s minds that Mars was much closer than it seemed.

However, in 2017, Musk suddenly announced the closure of the program. It turned out that the technology of landing on jet engines for a small spacecraft cannot be scaled up to the dimensions required for colonizing Mars. The project with the Martian Dragon was canceled, and all resources were transferred to the development of the more cargo-capable Starship.

Red Dragon reached the Martian surface only in vivid renderings. Source: planetary.org

Red Dragon reached the Martian surface only in vivid renderings. Source: planetary.org

Although Red Dragon never reached Mars, today its crew version, Crew Dragon, remains the most sought-after vehicle for delivering astronauts to the ISS. Just recently, as part of the Polaris Dawn commercial mission, a manned spacecraft reached an orbit 1,400 km above Earth, further than any manned spacecraft except those in the Apollo lunar program.

Hard-won reusability: Return of the first stage of Falcon 9

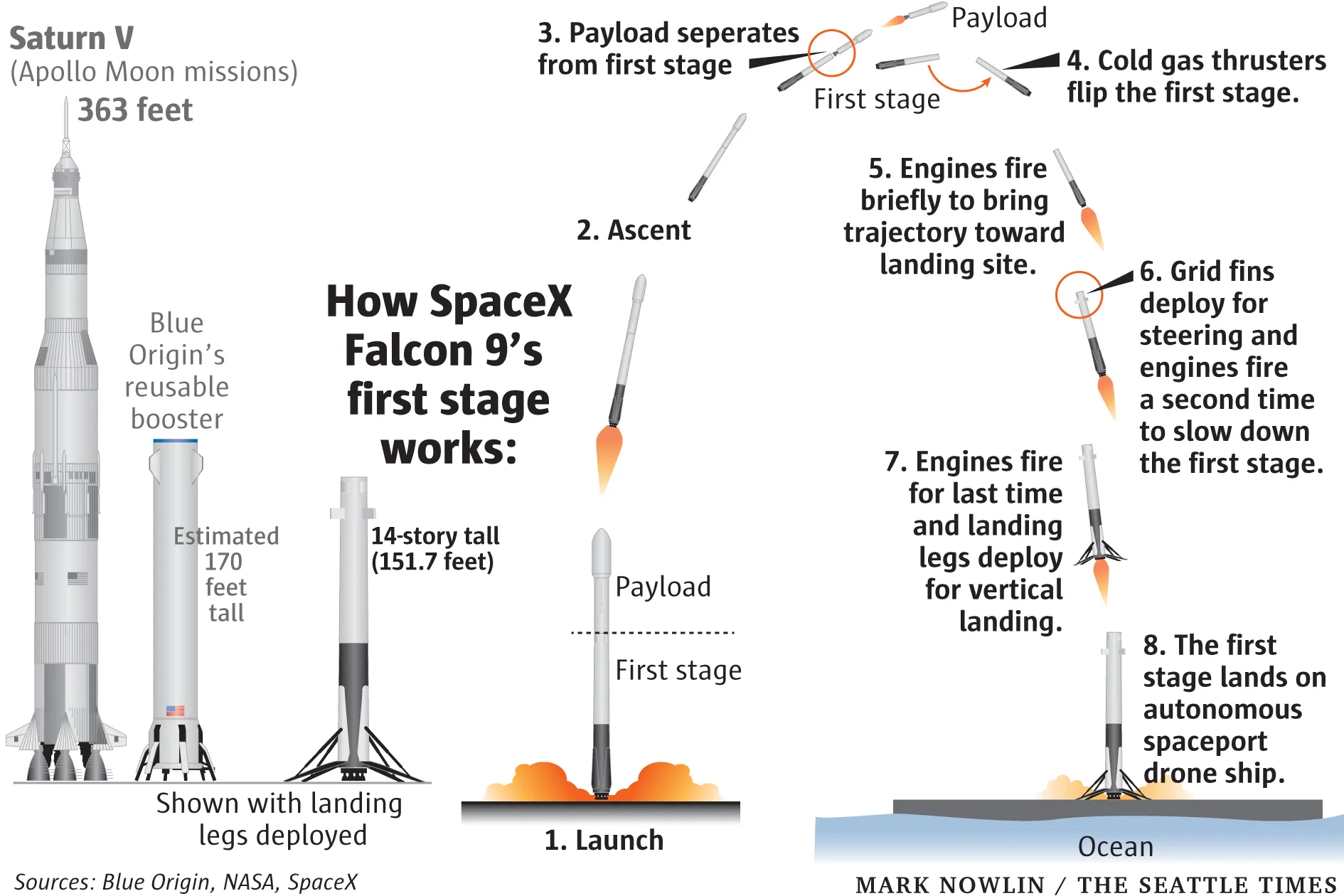

In the early 2010s, the idea of returning rockets to Earth seemed to most experts to be a waste of resources due to the approach to rocket construction at the time. In order for the rocket to land successfully, additional elements had to be installed on it: heavy landing struts, a control system, and grid rudders for the final stages of landing.

In addition, a significant portion of the fuel had to remain in the tanks for reverse braking impulse. According to preliminary estimates, this could consume between 20% and 40% of the payload that a classic single-use rocket could deliver into orbit. In dry figures, the approach did seem somewhat absurd: why build a giant rocket and use a third of its power to save the metal itself, instead of using that resource to launch more satellites into orbit?

The principle of returning the first stage of Falcon 9. Source: seattletimes.com

The principle of returning the first stage of Falcon 9. Source: seattletimes.com

However, Musk viewed reusable stages not through the prism of fuel efficiency, but through financial reporting. He claimed that fuel costs only about 0.3% of the total cost of the rocket, while the first stage alone can cost tens of millions of dollars. His logic was simple: it was better to sacrifice some of the payload capacity and deploy a couple of satellites less, but preserve the most expensive part of the system for the next flight. He compared it to aviation: “Imagine if, after every flight, you threw the plane away in a landfill — a ticket for it would cost millions.”

In 2011, Elon Musk began predicting that his Falcon 9 would become a fully reusable system within the next few years. The path to the actual implementation of the plan took about four years of iterative testing, during which the world witnessed a series of epic explosions: rockets fell onto barges, overturned, and shattered into pieces due to minor malfunctions in the supports. With his characteristic irony, Musk called these accidents “rapid unplanned disassembly” and continued to insist on the success of his approach, ignoring criticism.

The triumph occurred on December 22, 2015, when the first stage of Falcon 9 successfully landed on the landing pad at Cape Canaveral. This was one of the few predictions where Musk almost guessed correctly with the announced deadline — the technology became operational within five years of the initial announcements.

The final seconds of the historic first landing of Falcon 9. Source: arstechnica.com

The final seconds of the historic first landing of Falcon 9. Source: arstechnica.com

The only regret for the founder of SpaceX remains the fact that a month before the first successful landing of Falcon 9, Blue Origin’s New Shepard suborbital rocket also demonstrated a successful horizontal landing. After SpaceX’s success in December, Jeff Bezos even ironically congratulated Musk on Twitter with the phrase: “Welcome to the club.”

But despite all the jibes from competitors, the success story of the Falcon 9 reusable rocket stage became indicative, because for the first time Musk’s promise was not just about deadlines, but about a complete transformation of the aerospace industry itself. The success of Falcon 9 led to a radical reduction in the price of launching payloads into orbit, thanks to which SpaceX continues to dominate the space launch market today.

Starlink: Internet for everyone and “a million satellites” in reserve

In January 2015, during a speech in Seattle, Elon Musk publicly announced his plan to create a global satellite internet network for the first time. His initial promise sounded quite specific: to deploy a constellation of approximately 4,000 satellites that would provide fast and inexpensive access to the Internet anywhere on the planet. Back then, Musk said the system would be up and running in five years, and the money from the satellite constellation would be the main source of funding for building a city on Mars.

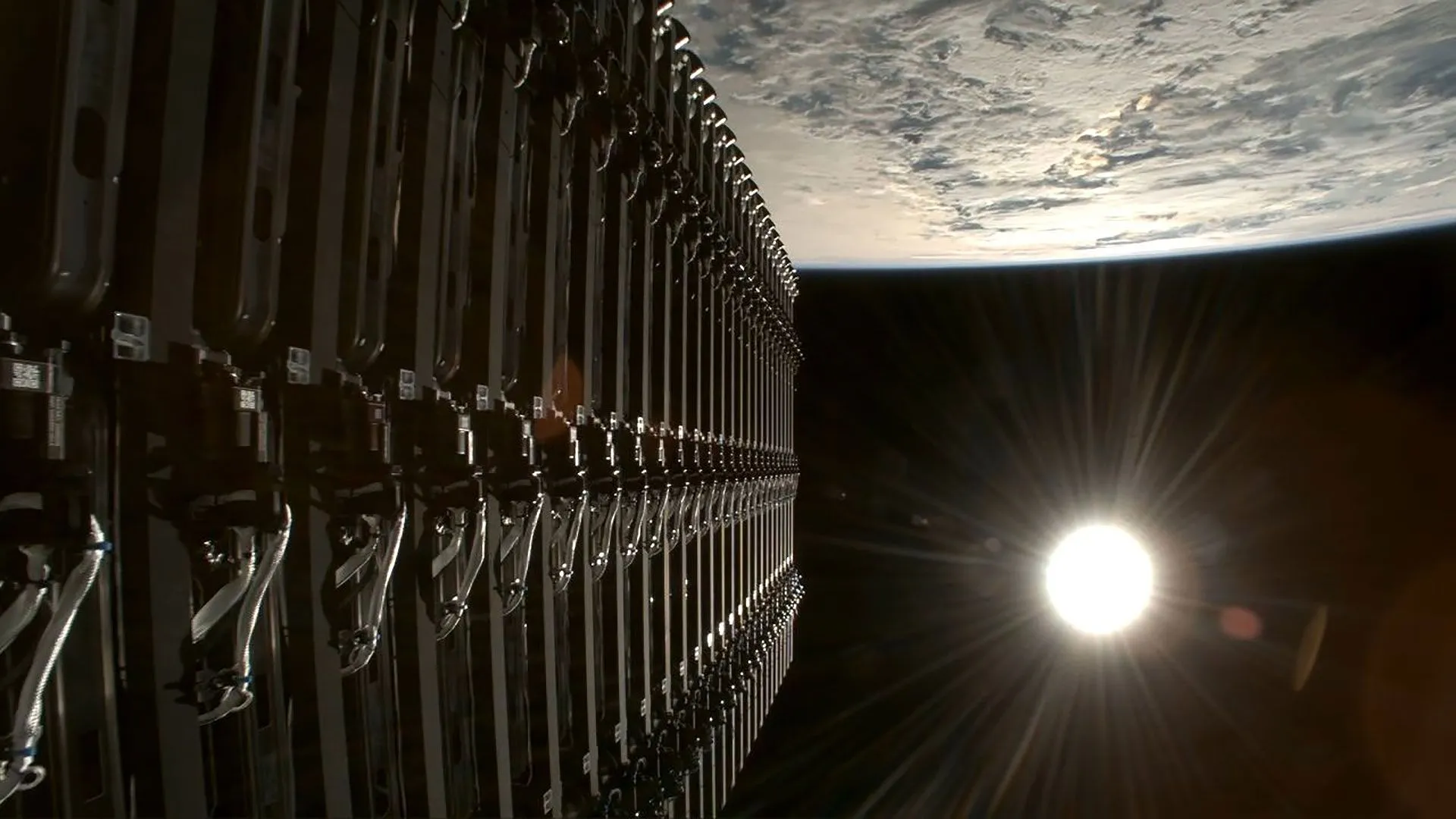

However, the promise regarding Starlink was almost the only one that Musk wanted to exceed. By 2019, the number of satellites had grown from 4,000 to 12,000, and SpaceX subsequently submitted an application to the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) to place 42,000 devices in low Earth orbit. Today, there are already more than 9,000 active Starlink satellites in orbit, or about two-thirds of all active satellites in the world.

A batch of Starlink satellites shortly before deployment. Source: techno-science.net

A batch of Starlink satellites shortly before deployment. Source: techno-science.net

If we compare the promise with reality, Starlink is perhaps Musk’s most successful promise in terms of implementation. Although the first commercial launches were delayed by 1-2 years, the speed of network scaling itself is impressive. In 2015, he promised that the system would be “cheaper than ground-based alternatives.” It’s debatable: the $599 cost of the terminal and the $120 monthly subscription fee remain prohibitively high for many regions of the world in comparison with cable internet. However, Musk kept his word in terms of speed: a signal delay (ping) of 25–40 ms makes satellite internet suitable even for online gaming, which was previously considered impossible.

Interestingly, Musk also promised that Starlink would cover up to 10% of traffic in major cities. However, this has not yet happened — due to physical limitations on bandwidth in densely populated areas, the service remains a priority for rural areas and conflict zones (his satellites are actively used by the Armed Forces of Ukraine to coordinate military operations and drone attacks). Starlink is also a story about how appetite grows with eating: SpaceX recently announced plans to deploy a satellite network of 1 million active satellites to create orbital data centers. Let’s see how this project turns out, but today we should recognize that the project, originally positioned as a wallet for Mars missions, has become a powerful tool for Musk’s geopolitical influence.

DearMoon: Unfulfilled dream of a lunar tourist

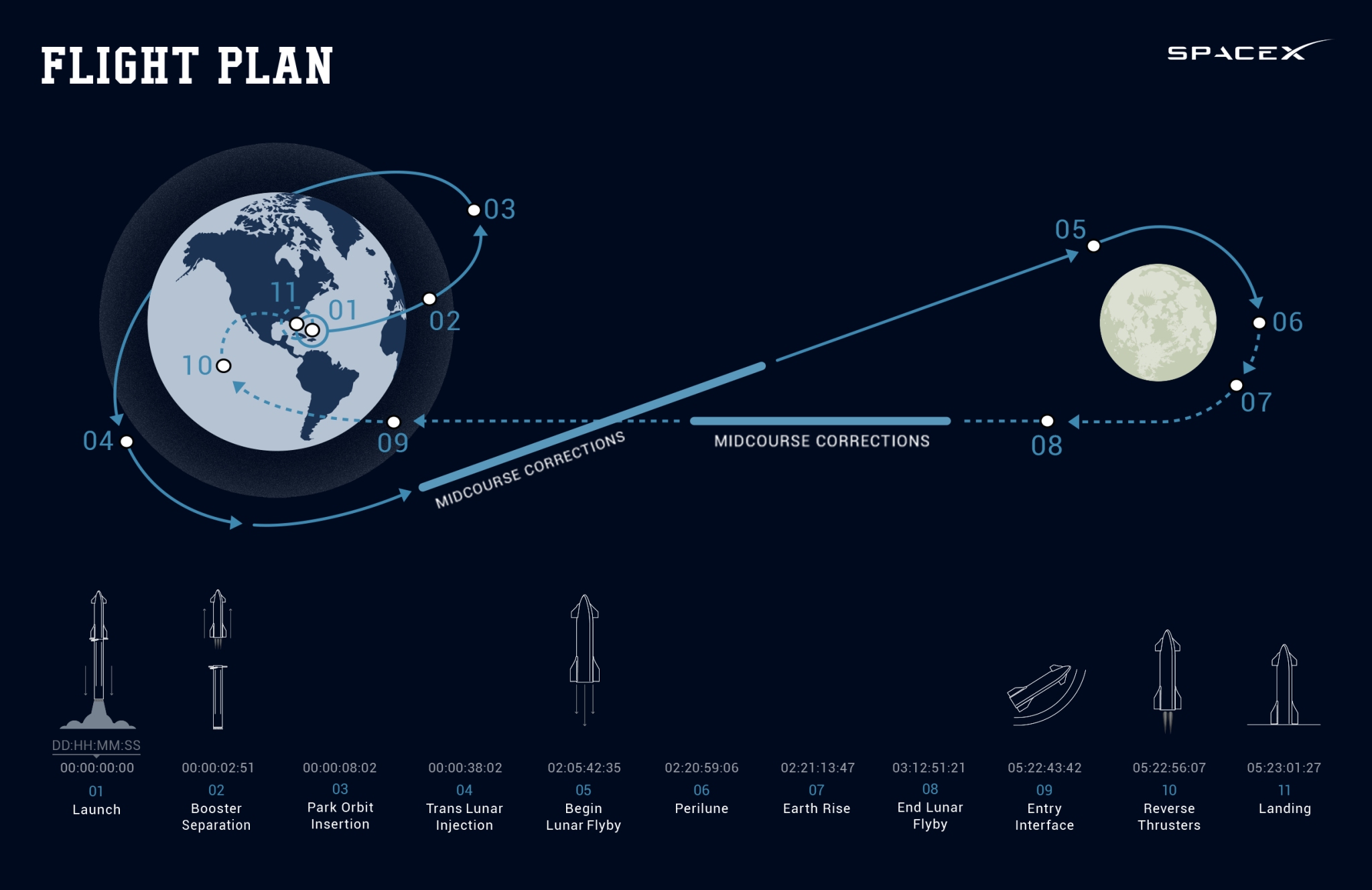

Talking about Musk’s current promises to build a fully autonomous city on the Moon in the next 10 years, it’s worth remembering how he announced the ambitious DearMoon project back in 2018. According to the plan, the mission was to be a tourist flight of the Starship rocket around the Moon for a group of eight artists selected through a special competition, led by Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa. The flight date was set for 2023. DearMoon was Musk’s first attempt to sell tickets for a space trip that was supposed to take place on a rocket whose working prototype simply did not exist. Later, this very circumstance would play a cruel joke on the businessman.

DearMoon mission flight plan. Source: dearmoon.earth

DearMoon mission flight plan. Source: dearmoon.earth

In subsequent years, the development of Starship proceeded much more slowly than planned. The explosions of prototypes in Texas, although part of the iterative process, did not bring the launch of the tourist mission any closer. In 2023, when the flight was supposed to take place, the spacecraft did not even reach a stable orbit in unmanned mode. The result was disappointing but predictable: in June 2024, Maezawa officially canceled the mission, stating that the timing of Starship’s readiness remained completely unpredictable. This was a serious blow to the reputation of SpaceX’s super-heavy rocket, which was only remedied by a series of successful Starship launches in 2025.

The DearMoon episode served as a good reminder that Musk’s predictions regarding humans in space are the most risky. When it comes to crew safety, regulators (such as the FAA) simply do not allow businessmen to move at the pace they want. On the other hand, this prevents the Starship itself from having an overly complex design, which would require significantly more testing and verification before astronauts could be placed inside.

It will be interesting to see how Musk’s new promise of a lunar city will be implemented, but we warn you — don’t expect too much from it. Past predictions suggest that Musk has thoroughly grasped Einstein’s principle of time relativity. His predictions are not an exact schedule, but rather an indicated vector of movement. Indeed, (and here we have to give credit to Musk) he often gets the dates of planned events wrong, but he is almost never wrong about their final outcomes.