Hidden deep within the Milky Way, a surprising discovery has been made: over 100 black holes tucked away in the Palomar 5 stellar stream. For years, scientists speculated about their existence, but it’s only now, thanks to the Gaia space observatory, that we’re uncovering their role in shaping our galaxy. This breakthrough, detailed in Nature Astronomy, provides new insights into how black holes form and influence their surroundings.

The Mystery of Stellar Streams

Stellar streams are long, delicate rivers of stars that extend across the Milky Way’s galactic plane. These streams have remained enigmatic for scientists due to their elusive nature, often appearing as faint traces in the sky. The discovery of such streams has become more common with the help of Gaia’s remarkable ability to map the Milky Way with high precision. In 2021, when researchers first announced the detection of Palomar 5’s tidal stream, it was noted in their study, published in Nature Astronomy, that the origin of these streams remained unclear.

“We do not know how these streams form, but one idea is that they are disrupted star clusters,” said astrophysicist Mark Gieles from the University of Barcelona in Spain. The idea that these streams might be the remnants of star clusters torn apart by gravitational forces offers a potential explanation. However, Gieles explained that none of the recently discovered streams have been linked to a star cluster. This makes it difficult to confirm the theory without further investigation.

“So, to understand how these streams formed, we need to study one with a stellar system associated with it. Palomar 5 is the only case, making it a Rosetta Stone for understanding stream formation and that is why we studied it in detail.”

The unique nature of Palomar 5’s stream offers a rare opportunity to examine these phenomena more deeply. The team used sophisticated N-body simulations to model the interactions between the stars in the cluster and hypothesize the role of black holes in shaping the stream’s structure.

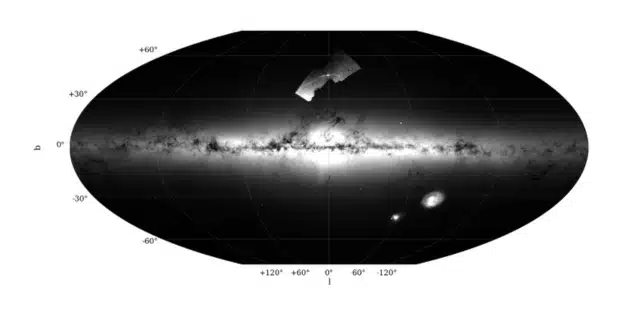

Map of the Milky Way plane obtained from data from the Gaia catalog (eDR3). The upper part shows a region where the Palomar 5 star cluster and its tidal tails are observed

Map of the Milky Way plane obtained from data from the Gaia catalog (eDR3). The upper part shows a region where the Palomar 5 star cluster and its tidal tails are observed

(DESI Legacy Imaging Survey, DECaLS/E. Balbinot, Gaia, DECaLS-DESI)

The Role of Black Holes in Palomar 5

The team’s findings suggest that black holes could play a crucial role in the dynamics of the Palomar 5 stream. It had previously been speculated that black holes might be found in the cores of globular clusters, but this new discovery offers the first substantial evidence of their influence. Gieles and his colleagues found that the number of black holes within Palomar 5 was far greater than anticipated.

“The number of black holes is roughly three times larger than expected from the number of stars in the cluster, and it means that more than 20 percent of the total cluster mass is made up of black holes,” Gieles said.

These black holes are not only numerous but also play a significant role in the cluster’s evolution. Each black hole in Palomar 5 is estimated to have a mass of about 20 times that of the Sun. They were formed during supernova explosions at the end of massive stars’ lives, when the cluster was still very young. The presence of these black holes helps explain the cluster’s unusual dynamics, with the black holes’ gravitational pull sending stars into the tidal stream.

This new insight is critical for understanding the ultimate fate of clusters like Palomar 5. Over the course of the next billion years, the cluster is expected to dissolve, with the remaining black holes being scattered into the galactic orbit. This could lead to an eventual increase in black hole mergers, offering opportunities for further research into their formation and interactions.

Future Implications: The Search for More Black Holes

The implications of this discovery extend far beyond Palomar 5. The study of globular clusters, especially those with large populations of black holes, could provide new answers to longstanding questions about black hole mergers. “It is believed that a large fraction of binary black hole mergers form in star clusters,” said astrophysicist Fabio Antonini of Cardiff University in the UK. This is particularly significant because it opens up new avenues for detecting binary black holes, which are incredibly difficult to observe directly.

“A big unknown in this scenario is how many black holes there are in clusters, which is hard to constrain observationally because we cannot see black holes,” Antonini explained.

However, the study introduces a groundbreaking method to estimate the number of black holes in star clusters. By analyzing the stars ejected from the cluster by the gravitational effects of these black holes, scientists can indirectly measure the black hole population. This method could revolutionize our understanding of black hole populations and help map out the invisible, yet abundant, cosmic objects that shape our universe.