A beam of light weaker than the bulb inside a refrigerator has delivered internet speed data from a satellite more than twenty times farther away than the International Space Station. The 2 watt laser, fired from geostationary orbit 36,000 kilometers above Earth, reached a ground telescope in southwestern China at 1 gigabit per second.

Researchers affiliated with Peking University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences designed the experiment to solve a problem that has limited optical communications for decades: holding a signal together through the planet’s churning atmosphere.

The demonstration arrives at a moment when low Earth orbit has become a crowded highway. Thousands of satellites operated by companies including SpaceX beam internet down from just a few hundred kilometers up, their constellations designed to minimize the delay that plagues real time applications.

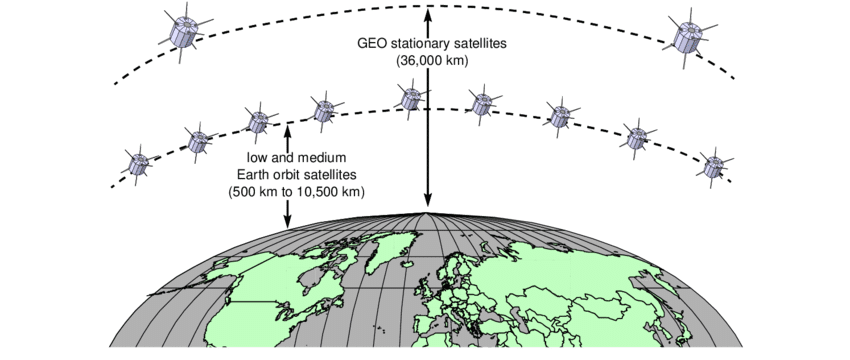

Geostationary satellites orbit the earth at 36 000 km while the emerging breed of low and medium earth orbiting satellites (LEOs and MEOs) orbit the Earth at heights ranging from 500 km to 10 500 km. Credit: Don Clarke

Geostationary satellites orbit the earth at 36 000 km while the emerging breed of low and medium earth orbiting satellites (LEOs and MEOs) orbit the Earth at heights ranging from 500 km to 10 500 km. Credit: Don Clarke

The Chinese approach inverts that logic entirely. A single spacecraft parked in geostationary orbit used a laser to achieve speeds the research team describes as five times faster than Starlink’s typical user links, raising immediate questions about whether the future of space communications might look less like a swarm and more like a mirror.

What makes the achievement startling is not merely the data rate but the wattage. Conventional radio transmitters on geostationary communications satellites often consume hundreds of watts to send signals over similar distances. The laser system operated at 2 watts, roughly equivalent to an LED night light, yet maintained signal integrity across a path length that has historically defeated optical attempts at high bandwidth.

The Atmosphere Was the Problem. They Bent It.

The central obstacle for any laser link from space is the atmosphere itself. Air turbulence distorts light waves, scattering them unpredictably before they reach the ground. For a beam originating in geostationary orbit, the distortion accumulates across the full atmospheric thickness, a problem less severe for low Earth orbit satellites that sit much closer to the planet.

Researchers addressed this through a dual stage process designated AO MDR synergy. The ground terminal, a 1.8 meter telescope at the Lijiang Observatory, contained 357 individually controlled micro mirrors that reshaped the incoming wavefront in real time, canceling distortions caused by atmospheric cells.

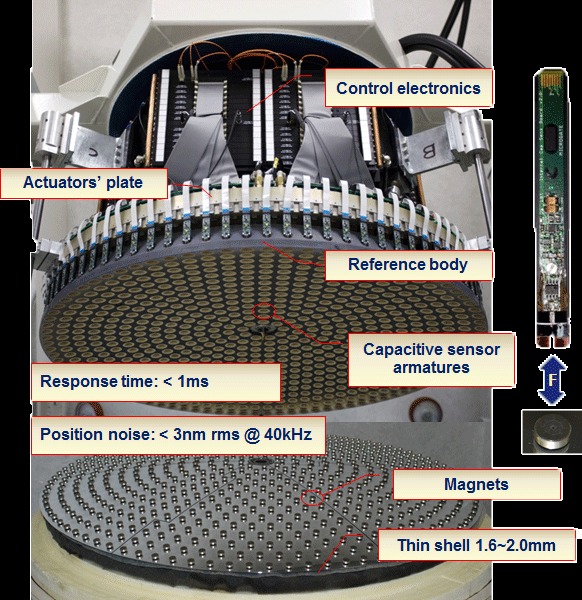

Components of an adaptive secondary mirror for a telescope, which uses actuators to control a thin mirror’s shape. Credit: Microgate

Components of an adaptive secondary mirror for a telescope, which uses actuators to control a thin mirror’s shape. Credit: Microgate

After correction, the light passed through a multi plane converter that split it into eight separate mode channels. An algorithm then selected the three strongest signals among those channels, discarding paths degraded by residual turbulence while preserving the most coherent data.

Data from the experiment shows the technique raised the proportion of usable signals from 72 percent to 91.1 percent. The gain of nearly 20 percentage points represents the difference between intermittent connectivity and a stable link capable of sustained gigabit transmission.

Why Geostationary Beats the Swarm for Speed

The choice of geostationary orbit carries inherent trade offs that distinguish this approach from low Earth broadband constellations. Propagation delay for a signal traveling to and from 36,000 kilometers approaches 240 milliseconds round trip, a figure that cannot be reduced regardless of bandwidth. That latency renders geostationary links unsuitable for applications requiring real time interaction, such as voice calls or video conferencing.

Low Earth systems like Starlink reduce that delay to 20 to 40 milliseconds by operating at altitudes near 550 kilometers. They achieve this at the cost of constellation size: thousands of satellites must continuously hand off signals as they pass overhead. The geostationary alternative offers continuous coverage of a fixed region from a single spacecraft, trading latency for mechanical simplicity.

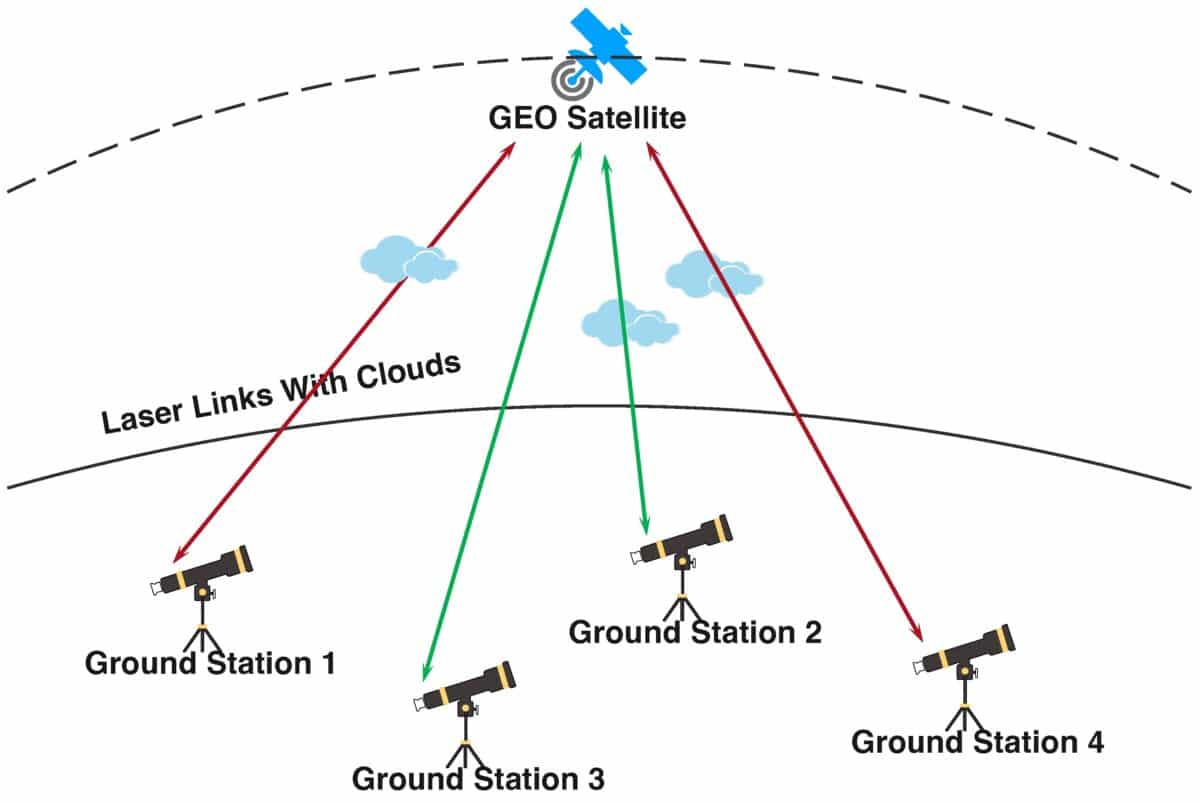

an SGLC system containing one GEO satellite and four candidate ground stations with a scheduling period of one time slot. Credit: Lyu, P., Zhao, K., & Zhao, H. (2025)

an SGLC system containing one GEO satellite and four candidate ground stations with a scheduling period of one time slot. Credit: Lyu, P., Zhao, K., & Zhao, H. (2025)

The data rate of 1 Gbps exceeds typical Starlink user speeds by a factor of approximately fifteen based on published median measurements, though direct comparison is complicated by different measurement points. The Chinese demonstration measured a dedicated laser downlink, while Starlink user speeds reflect shared radio frequency connections through consumer terminals subject to network congestion and atmospheric effects at different frequencies.

What the Journal Paper Actually Says

The work draws on extended investigation into free space optical communications conducted across multiple Chinese institutions. Professor Wu Jian from Peking University of Posts and Telecommunications and Liu Chao from the Chinese Academy of Sciences led the research team, with experimental validation performed at the Lijiang facility in Yunnan province.

The findings appeared in Acta Optica Sinica, a peer reviewed Chinese language journal covering optics and photonics. The publication disclosed the adaptive optics configuration and mode diversity reception method but did not specify the modulation format or forward error correction coding used in the transmission. Those parameters influence the relationship between raw optical power and achieved data rate, and their absence leaves certain aspects of the demonstration unavailable for independent replication.

Researchers also did not state whether the experiment was repeated under varied atmospheric conditions or at different times of day. The Lijiang site sits at approximately 2,500 meters elevation, which reduces the atmospheric path length and water vapor content compared to sea level locations. Operational systems would require multiple geographically distributed ground stations to maintain availability through cloud cover, which blocks optical signals completely regardless of adaptive optics performance.

The Catch You Cannot See Through

The most significant unresolved question involves atmospheric availability statistics. Optical signals cannot penetrate thick cloud cover, and even thin cirrus can attenuate beams below detectable thresholds. Geostationary optical links would require either a network of ground stations spaced widely enough that at least one is clear at any given time, or hybrid terminals with radio frequency backup for degraded conditions.

Researchers have not published availability modeling for the Lijiang site or proposed locations for additional stations. Clear sky statistics vary dramatically by region, with desert and high altitude sites offering the best performance while maritime and tropical locations present frequent cloud cover. A global geostationary relay system would need stations in multiple climatic zones, each equipped with meter class telescopes and adaptive optics systems comparable to the experimental configuration.

The 1.8 meter aperture used in the demonstration also exceeds the size practical for widespread deployment. Consumer terminals for low Earth orbit satellite internet measure roughly 50 centimeters across. Geostationary optical ground stations of this scale would function as backbone aggregation points, collecting high capacity data and distributing it through terrestrial fiber networks, rather than serving end users directly.