The name 3I/ATLAS might be the sort of designation that briefly lights up science feeds, but the quieter fear NASA officials are trying to drag into the open is far less cinematic: the rocks we have not found, drifting through a stubborn ‘blind spot’ where our telescopes struggle to look. What makes it unsettling is not the Hollywood-sized apocalypse, but the more plausible, more political nightmare of a regional strike catastrophic for a city, yet easy to ignore until it is suddenly not.

On Feb. 16, at the American Association for the Advancement of Science annual meeting in Phoenix, Dr. Kelly Fast NASA’s acting Planetary Defense Officer put a number on that unease. Roughly 15,000 near-Earth objects measuring at least 140 metres across remain undiscovered, she warned, and NASA has only reached about ‘40 percent‘ of its detection goal for objects of that size. Big, civilisation-altering asteroids are largely tracked already; tiny debris hits Earth frequently and usually burns up; it is the middle category that is nasty precisely because it sits in the gap between complacency and panic.

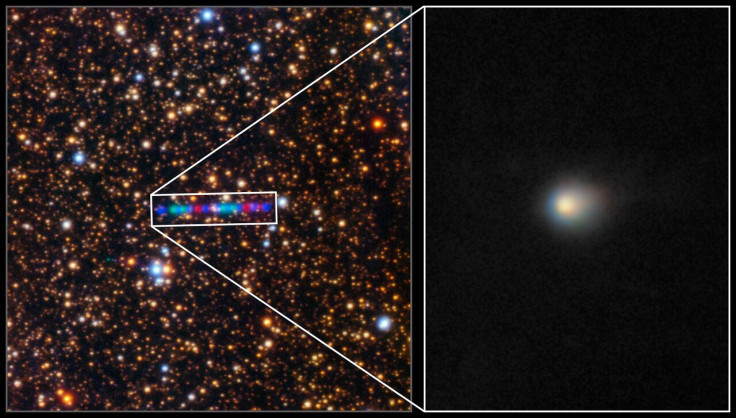

3I/ATLAS

NSF NOIRLab

3I/ATLAS and the Blind-Spot Problem We Don’t Like Admitting

Here is the part that does not sit comfortably with our fondness for technological reassurance: even powerful telescopes cannot reliably spot what they cannot sensibly see. Many near-Earth asteroids spend much of their time on trajectories interior to Earth’s orbit, effectively hiding in the sun’s glare. Ground-based observatories have only short windows at twilight to hunt them without being blinded. Add the awkward fact that a large fraction are dark, carbon-rich bodies that reflect little sunlight, and you begin to understand why ‘unknown asteroids’ are the real risk: they are not announcing themselves with a handy reflective sheen.

The stakes are not abstract. A 140-metre ‘city-killer’ impact carries the kind of energy that can wipe out a major urban area. Science magazine describes it as roughly 300 million tons of TNT. That is not ‘end of the world’ territory, which is precisely why it is politically treacherous: it is ‘only’ an event that could shred one region, one economy, one country’s sense of normality, while the rest of the planet scrolls on.

3I/ATLAS

IBTimes UK/YouTube Screenshot

3I/ATLAS, DART and the Uncomfortable Gap Between Tests and Reality

NASA can point to a genuine success story: the Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART. In September 2022, the spacecraft deliberately slammed into the asteroid moonlet Dimorphos at roughly 14,000 miles per hour to prove that deflection is possible. It worked. The impact measurably changed Dimorphos’ motion — an engineering triumph and, for once, a rare piece of good news in the planetary-defence file.

And yet Dr. Nancy Chabot of Johns Hopkins University, who led the DART mission, underlined the less flattering reality in Phoenix: there is no equivalent spacecraft sitting ready to launch if a genuine threat appears. If that sounds maddening, it should. A one-off demonstration is not a standing capability, and ‘no immediate launch option’ is a polite way of saying we are still improvising. Chabot also flagged the bigger structural issue: preparedness needs sustained investment, not occasional bursts of attention when a dramatic object swings by.

Scientists baffled as 3I/ATLAS displays sun-locked jet with odds of natural alignment near zero

Pixabay

That last point landed harder because we’ve just had a recent reminder of how jittery the system can get. Asteroid 2024 YR4 passed close to Earth on Dec. 25, 2024; early projections raised collision fears for 2032 before later analysis ruled out an Earth impact. The episode, scientists argued, exposed monitoring gaps — less a near-miss thriller than a case study in how quickly uncertainty fills the space where detection should be.

NASA’s answer is, essentially, to stop relying on luck and twilight. The Near-Earth Object Surveyor, an infrared space telescope designed first and foremost for planetary defence, has a planned launch in September 2027, with the aim of finding nearly all near-Earth asteroids at least 140 metres in size. Infrared matters because asteroids, dark or shiny, ‘glow’ thermally: you can detect what you cannot easily see in reflected sunlight, and you can estimate their size more accurately.

After 3I/ATLAS, the temptation will be to chase the next headline object and forget the dull, methodical work. NASA’s own messaging in Phoenix was a nudge in the opposite direction: the real menace is the unglamorous inventory we still have not taken.