New analysis of 2017 images from the Hubble Space Telescope of the Jupiter family comet 41P/Tuttle–Giacobini–Kresak (41P/TGK) shows that the comet’s nucleus changed its rotation direction between April and December 2017. Although this behavior is not unprecedented, the changes in the rotation of 41P/TGK were deemed “particularly dramatic” in a new study by astronomers.

The comet changed its direction of rotation. Source: phys.org

The comet changed its direction of rotation. Source: phys.org

Increase in rotation period

Jupiter family comets are defined by their strong gravitational interactions with Jupiter, their relatively short period of less than 20 years, and their low orbital inclination. Comet 41P/TGK was brought into its current orbit after its last close encounter with Jupiter about 1,500 years ago and is expected to remain in a similar orbit for another 10,000 years or so.

41P/TGK entered the part of its orbit where it is closest to the Sun (its perihelion) in April 2017, which allowed it to be placed in a position convenient for observation. Studies during this period showed a sharp increase in the rotation period of 41P/TGK (a slowdown in its rotation) and suggested that rapid changes in rotation were probably caused by gas emissions from the nucleus. However, the lack of data after perihelion and accurate size estimates led to uncertainty.

“Remarkable observations from 2017 show a rapid increase of the rotation period of the nucleus, deduced both photometrically and from rotating jets. The period more than doubled, from P ∼20 hours to ∼53 hours, over the course of two months near perihelion. The simplest explanation of the changing period is that the nucleus was torqued by recoil forces from anisotropic outgassing, as has been widely demonstrated in other comets,” explains the author of the latest study.

Comet rotates in the opposite direction

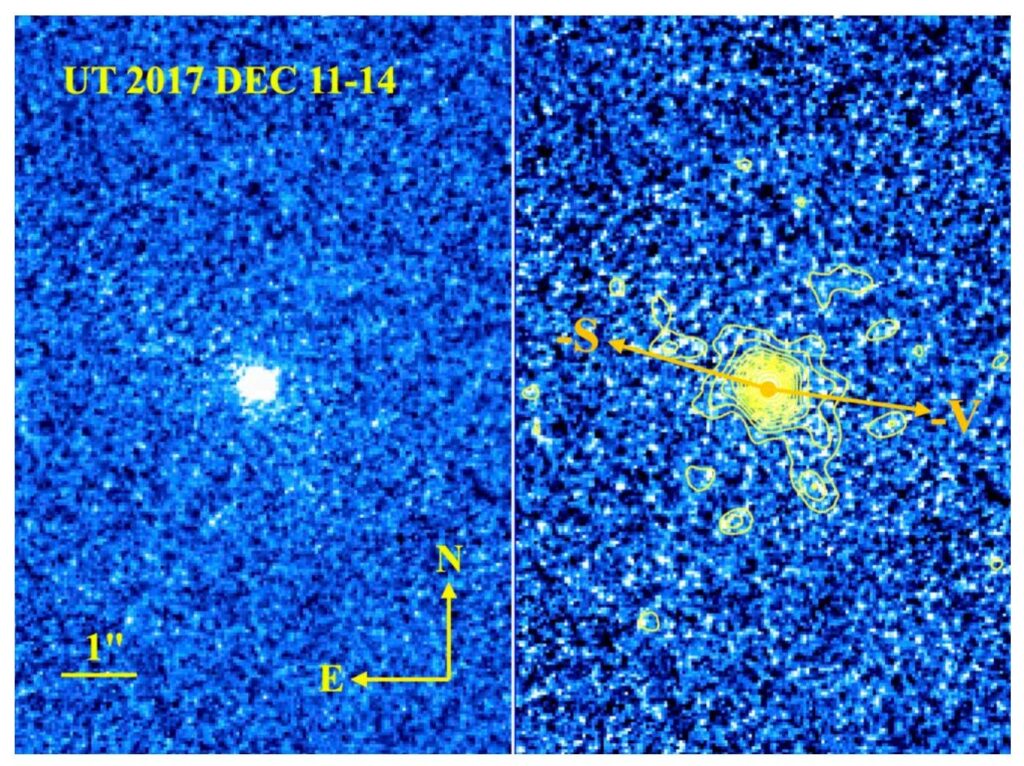

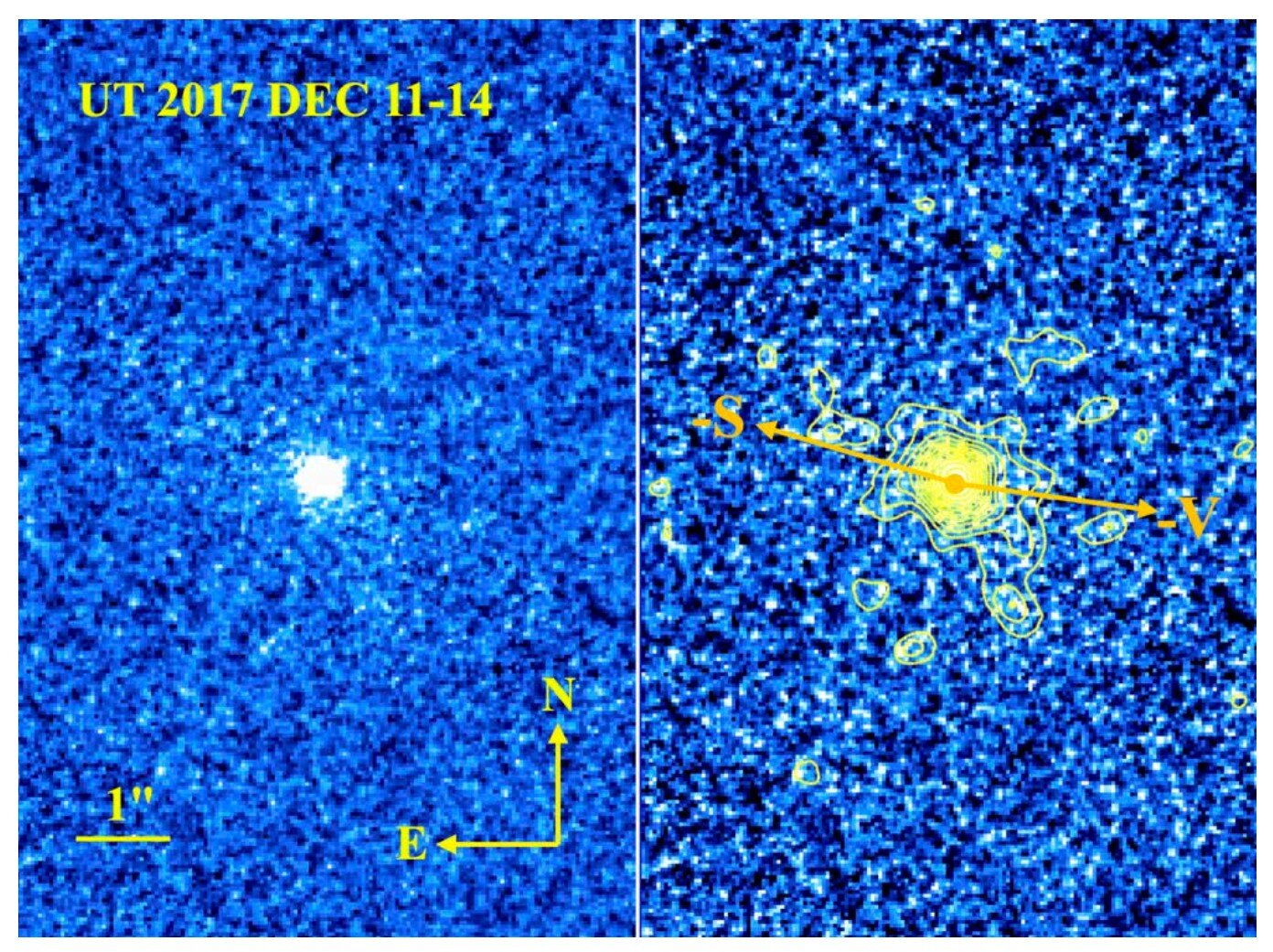

After initial data was received in April, comet 41P/TGK disappeared from view by December of that year. Although images of the comet were taken when 41P/TGK reappeared in view, the data was only recently fully analyzed by astronomer David Jewitt of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Using images from the Hubble Space Telescope taken in December 2017, he performed photometry to estimate the size of the comet’s nucleus and analyzed the light curve to determine its rotation period. Then he compared the results with other data to estimate the dimensions and modeled the evolution of rotation using the observed moments of force and mass loss rates.

The most striking discovery was evidence supporting a reversal in the direction of rotation of 41P/TGK between April and December 2017. The results showed that the orbital period had decreased to 14.4 hours, significantly shorter than at the beginning of 2017. The shorter “days” of the comet meant that its rotational speed had increased again.

According to Jewitt, this means that the comet should have slowed down and stopped completely, and then started rotating in the opposite direction, increasing its rotational speed. The data indicates that the stopping point likely occurred in June 2017.

Additional results include measuring the comet’s nucleus at approximately 500 m and a decrease in the active fraction of the nucleus, which fell from approximately 2.4 in 2001 to approximately 0.14 in 2017. These results indicate the evolution of the surface on the comet.

Life expectancy estimates

The study also shows that these chaotic changes in the nucleus of 41P/TGK could mean that it is at risk of being destroyed by rotation within decades, which is significantly shorter than its orbital lifetime. Although the estimated dynamic lifetime is about 10,000 years, rapidly changing rotation could cause the nucleus of 41P/TGK to break apart from rotation in about 25 years, according to a new study analysis.

Jewitt explains this discrepancy by the fact that TGK may be in an atypically active state. For example, it is possible that sublimation is normally suppressed more completely by the refractory shell than at present, which reduces the rate of mass loss and the associated moments of force, and thus lengthens the time scale for spin-up.

According to phys.org