A view of the potential merger between the Milky Way and Andromeda as it may appear in Earth’s night sky in 3.75 billion years. Credit: ESA/NASA

A view of the potential merger between the Milky Way and Andromeda as it may appear in Earth’s night sky in 3.75 billion years. Credit: ESA/NASA

For nearly a century, astronomers have known that the universe is expanding. Most galaxies are carried outward with the flow of space itself.

Yet one stubborn exception has lingered in our cosmic backyard. The Andromeda galaxy is racing toward the Milky Way, while many other nearby galaxies slip away. In fact, the two galaxies are supposed to collide. The Andromeda Galaxy will merge with the Milky Way in approximately 4.5 billion years, forming a new elliptical galaxy often referred to as “Milkomeda”.

Now, a new set of detailed computer simulations suggests the answer to this bizarre attraction may lie in an unseen structure of dark matter stretching tens of millions of light-years across. Instead of surrounding our cosmic neighborhood in a sphere, much of the mass just beyond it appears to form a vast, flattened sheet.

The finding, reported in Nature Astronomy, offers a way to reconcile long-standing puzzles about galaxy motions with the leading model of cosmology.

A Strangely Quiet Neighborhood

Astronomers trace cosmic expansion through the “Hubble flow,” the steady recession of galaxies first measured in the 1920s. Distance and speed usually rise together.

But the Local Group—home to the Milky Way, Andromeda, and dozens of smaller galaxies—does not fit neatly into that pattern. Andromeda is approaching at roughly 110 kilometers per second, while many slightly more distant galaxies drift outward.

Scientists have struggled to explain why the Local Group’s gravity does not pull those neighbors inward. Earlier work showed that dark matter halos around the Milky Way and Andromeda contain far more mass than their visible stars, enough to draw the two galaxies toward a future collision.

Still, that attraction seemed too weak to influence galaxies just beyond the group.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

To investigate, researchers reconstructed the plausible region’s history from the early universe to today. Their simulations began with the faint patterns in the cosmic microwave background and evolved forward until they reproduced the present-day masses, positions, and velocities of the Milky Way, Andromeda, and 31 nearby galaxies.

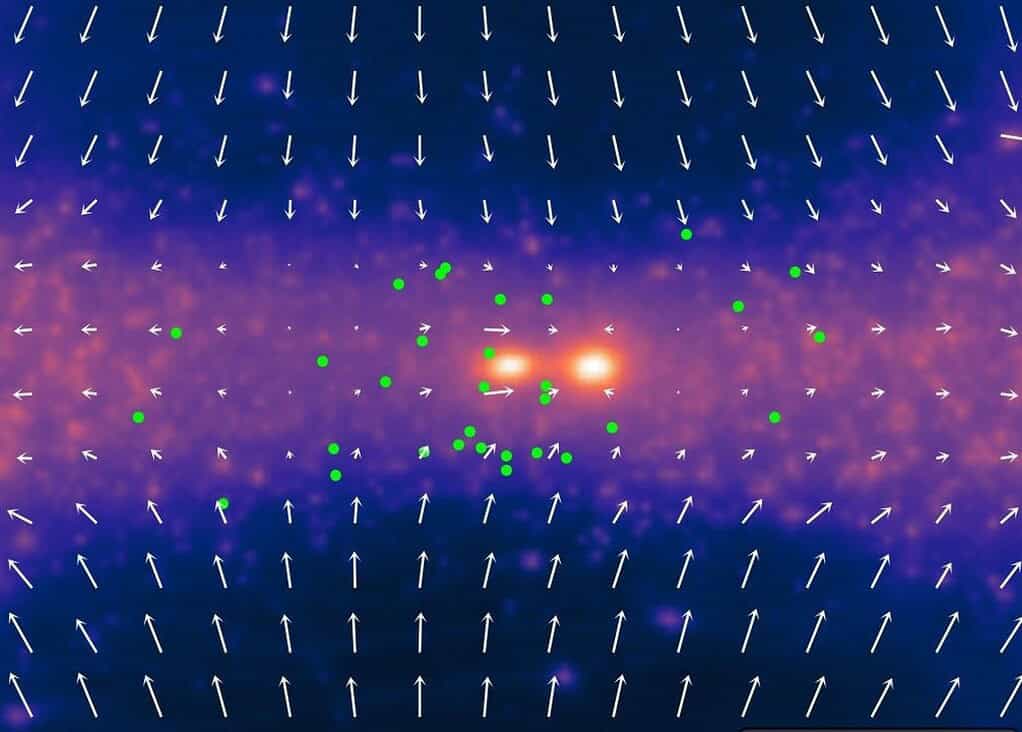

Simulated movement and speed (indicated by the length of the arrows) of objects surrounding the Local Group (centre). Credit: Ewoud Wempe/Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics

Simulated movement and speed (indicated by the length of the arrows) of objects surrounding the Local Group (centre). Credit: Ewoud Wempe/Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics

The result was unexpected. The simulations showed that matter around our cosmic neighborhood formed a vast, flat layer, with enormous empty regions stretching above and below it. This flattened arrangement, the researchers found, is one of the few configurations that can simultaneously explain both how nearby galaxies are moving and how much mass the Milky Way and Andromeda contain.

Because many neighboring galaxies lie within this plane, gravity from distant matter in the sheet counteracts the inward pull of the Local Group. Outside the plane, there are few galaxies at all—only emptier regions of space.

The simulations show that this flattened geometry changes how gravity works on large scales. In a spherical distribution, only the mass inside a given radius matters for motion.

In a sheet, distant matter can tug outward, boosting recession speeds and keeping nearby galaxies moving away despite the Local Group’s pull.

This structure also mirrors features astronomers already see in the nearby universe: a “Local Sheet” of galaxies bordered by underdense voids. The new work links those visible patterns directly to the hidden distribution of dark matter.

“We are exploring all possible local configurations of the early universe that ultimately could lead to the Local Group. It is great that we now have a model that is consistent with the current cosmological model on the one hand, and with the dynamics of our local environment on the other,” said study leader Ewoud Wempe in a statement.

The results suggest the standard cosmological framework—known as Lambda Cold Dark Matter—remains intact. Allowing the universe’s local structure to be uneven rather than spherical resolves the tension between galaxy motions and mass estimates.

Future observations may provide a decisive test. The simulations predict strong flows of matter falling toward the sheet from the sparse regions above and below, but few nearby galaxies exist there to measure the effect directly.

If astronomers discover more distant galaxies above and below this plane racing inward at high speed, it would strengthen the idea that our cosmic neighborhood is shaped more like a wall than a bubble.