As far as we know, life in our Solar System emerged only here on Earth – the Sun’s ‘Goldilocks’ planet

– under conditions that were just right for liquid water to exist.

Only here did life’s ingredients take root. Only here did water, nutrients, an energy source, a clement atmosphere, survivable temperatures and pressures, and benign radiation fall happily into equilibrium.

Not long after its formation, the earliest life stirred. Multilayered ‘microbial mats’, fossilised ‘stromatolites’ – sediments created by photosynthetic organisms – and precipitates from hydrothermal vents have been found that are at least 3.5 billion years old.

Credit: 3000ad / Getty Images

Credit: 3000ad / Getty Images

Life, it seems, favoured Earth as enthusiastically as the fairytale Goldilocks favoured the baby bear’s perfect porridge.

But there are tantalising signs elsewhere in the Solar System that point to alien life having also taken root.

Let’s look at the most likely contenders.

Microbes on Mars Illustration showing Jezero Crater — the landing site of the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover — as it may have looked billions of years go on Mars, when it was a lake. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Illustration showing Jezero Crater — the landing site of the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover — as it may have looked billions of years go on Mars, when it was a lake. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Our next-door planet, cinnamon-red Mars, is a desiccated, subfreezing, radiation-drenched place with a thin carbon dioxide atmosphere, no global magnetic field and surface pressures about 100 times weaker than Earth’s.

Yet 3.7 billion years ago, Mars may have been quite different.

Girdled by a thicker atmosphere, warmed by a moderate greenhouse effect and shielded from solar radiation by a stable magnetic field, it could have had higher surface temperatures – and even life.

The question of Martian life has vexed us for generations. Today’s Mars cannot sustain stable bodies of liquid water.

But in its infancy, it possessed perhaps twice as much water as Earth does now.

Space probes revealed dried-up riverbeds, deep valleys and eroded grooves in bedrock, strongly hinting at water activity.

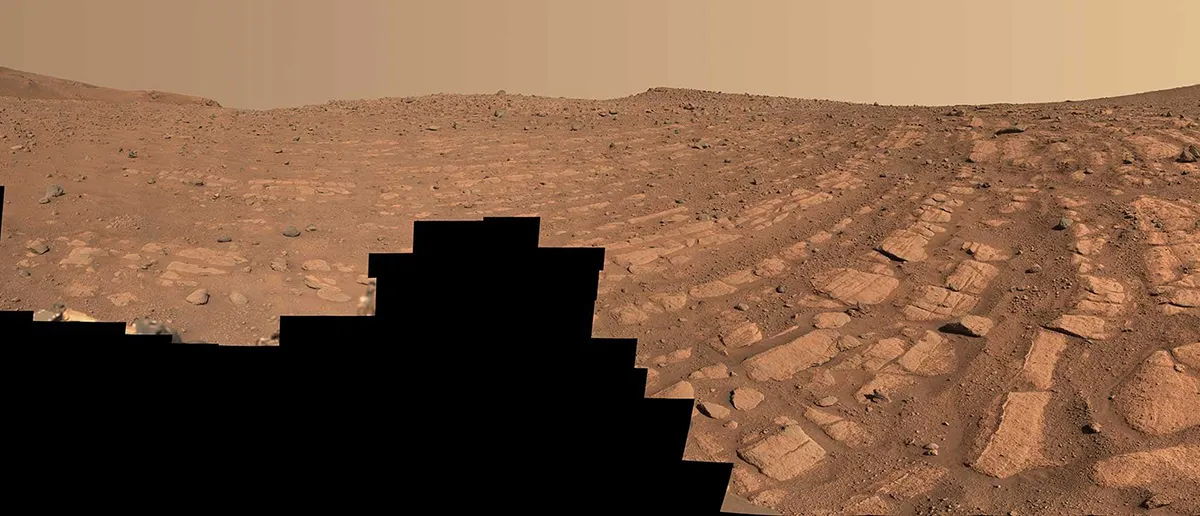

Bands of rocks on Mars in a region called ‘Skrinkle Haven’ that could have been formed by a fast, deep river. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS

Bands of rocks on Mars in a region called ‘Skrinkle Haven’ that could have been formed by a fast, deep river. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS

NASA’s Curiosity rover found sediments left by vigorous, ankle-deep flowing water.

Ancient lakes may have rivalled the Caspian Sea or Russia’s Lake Baikal in scale. Rushing water surged 10 times faster than the Mississippi River.

Minerals like smectite, jarosite and haematite that only form in water’s presence have been discovered.

A long-extinct ocean – as huge as the Arctic Ocean – could once have dominated Mars’s northern hemisphere.

Eventually, Mars’s magnetic field decayed, solar radiation stripped much of the atmosphere and its water escaped into space, or was bound in the polar caps or entrapped in subsurface permafrost.

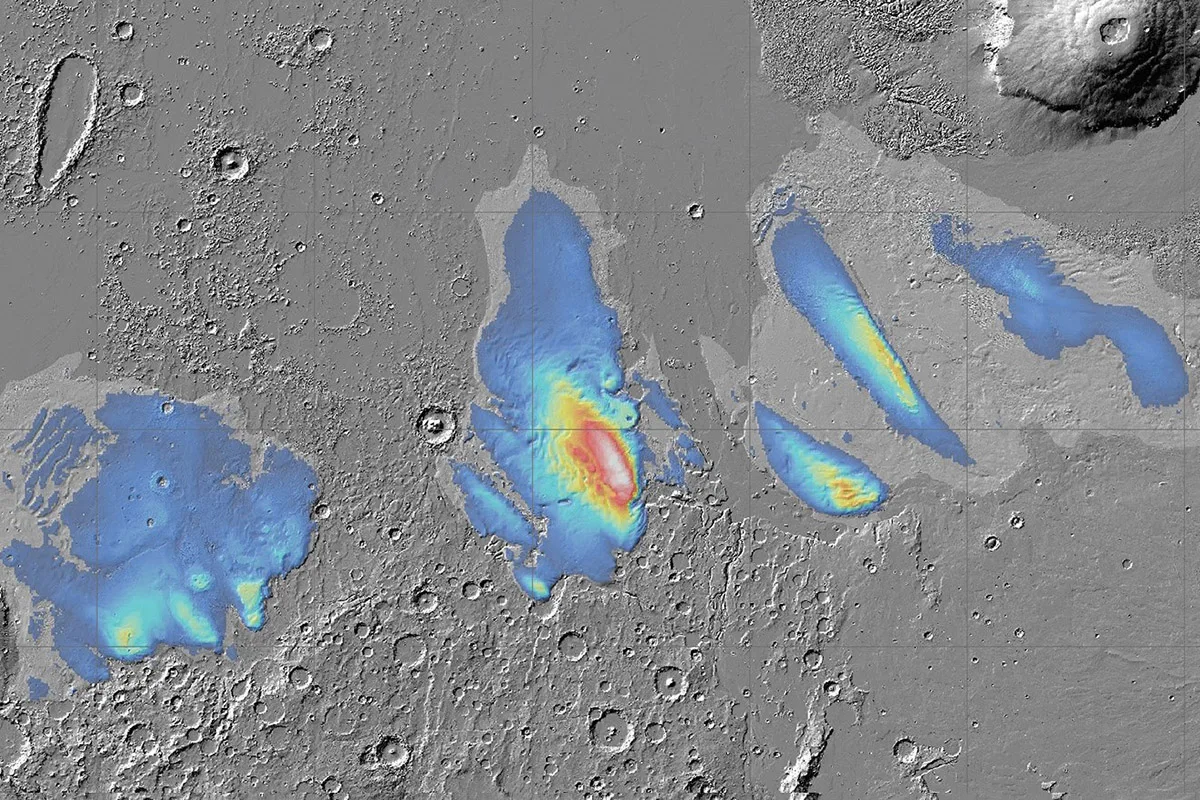

But NASA’s InSight lander revealed liquid water might still exist 10–20km (6–12 miles) under the surface and ESA’s Mars Express hinted at subglacial lakes beneath the south polar cap.

Map showing the thickness of a deposit thought to be water ice at Mars’s equator in the Medusae Fossae Formation, captured by ESA’s Mars Express orbiter. Credit: ESA

Map showing the thickness of a deposit thought to be water ice at Mars’s equator in the Medusae Fossae Formation, captured by ESA’s Mars Express orbiter. Credit: ESA

On Earth, wherever there is water, there tends to be life.

Curiosity’s exploration of Gale Crater – likely an ancient lake – discovered neutral pH levels, low salinity, minerals usable by microorganisms and, most recently, long-chain carbon molecules – some of the key building blocks of life.

At Jezero Crater, NASA’s Perseverance rover found odd, leopard-like ‘spots’ on a rock, suggestive of possible microbial life.

NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover captured this image of a rock with ‘leopard spots’ nicknamed Cheyava Falls on 18 July 2024. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s Perseverance Mars rover captured this image of a rock with ‘leopard spots’ nicknamed Cheyava Falls on 18 July 2024. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

But water is only part of life’s puzzle. Other environmental factors are needed to help life not just survive but thrive.

Simulations indicate that if multiple ‘lethal factors’ – a lack of nutrients, surface temperatures of –63°C (–82°F) (Mars’s average), the sterilising effect of solar radiation and the ubiquitous presence of toxic perchlorate in Mars’s soil – are combined, the likelihood of life plummets, even in purportedly ‘habitable’ areas.

If life ever arose on Mars, it probably occurred at microscopic levels in liquids or sediments.

‘Halotolerant’ organisms capable of enduring total darkness, low nutrient levels and high pressures could exist in subglacial lakes or near geothermal hotspots.

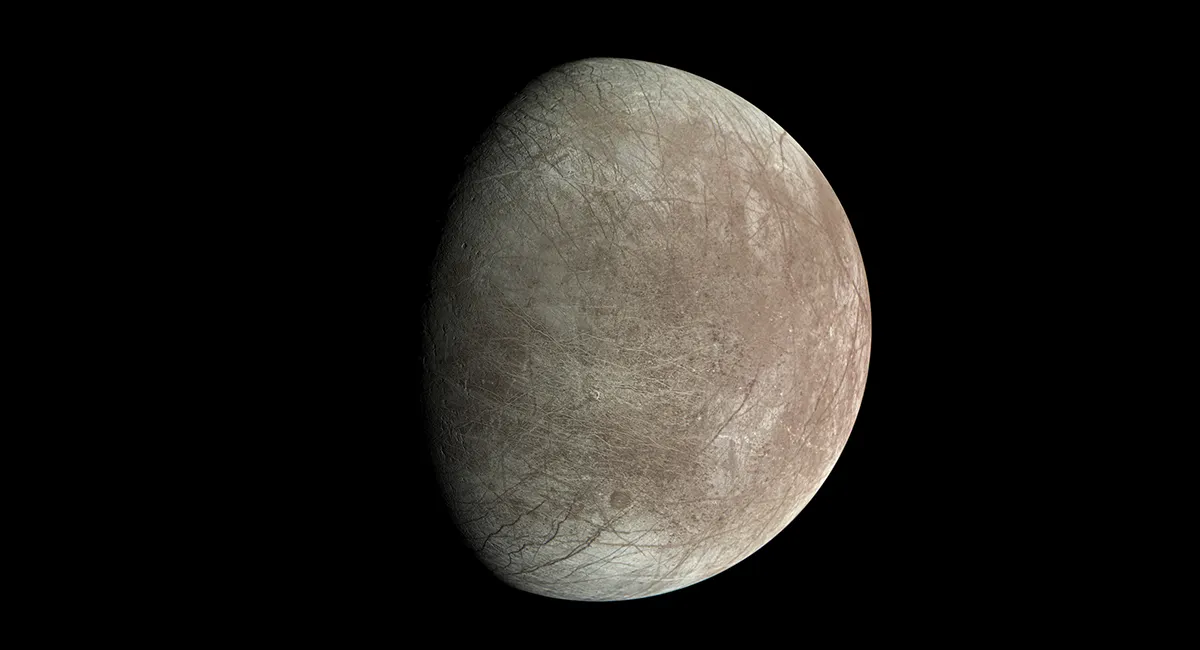

Rock-eaters on Europa Image of Jupiter’s moon Europa captured by NASA’s Juno spacecraft. Image data: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS. Image processing: Björn Jónsson (CC BY 3.0)

Image of Jupiter’s moon Europa captured by NASA’s Juno spacecraft. Image data: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS. Image processing: Björn Jónsson (CC BY 3.0)

Another contender for life outside our planet is Jupiter’s moon Europa. It may harbour a 100km-deep (60-mile) ocean under its granite-hard icy crust.

Ten times deeper than the deepest part of Earth’s seabed, the Challenger Deep, it could hold two to three times more water than all our oceans combined.

Europa’s chaotic terrain, crisscrossed by ridges and troughs, may be caused by the subsurface ocean rhythmically disgorging its salt-laden innards onto the frozen surface.

Magnetometer data from NASA’s Galileo probe was consistent with the ocean’s existence.

Despite temperatures of –160°C (–260°F), it might remain liquid thanks to internal heat and tidal flexion induced by Jupiter.

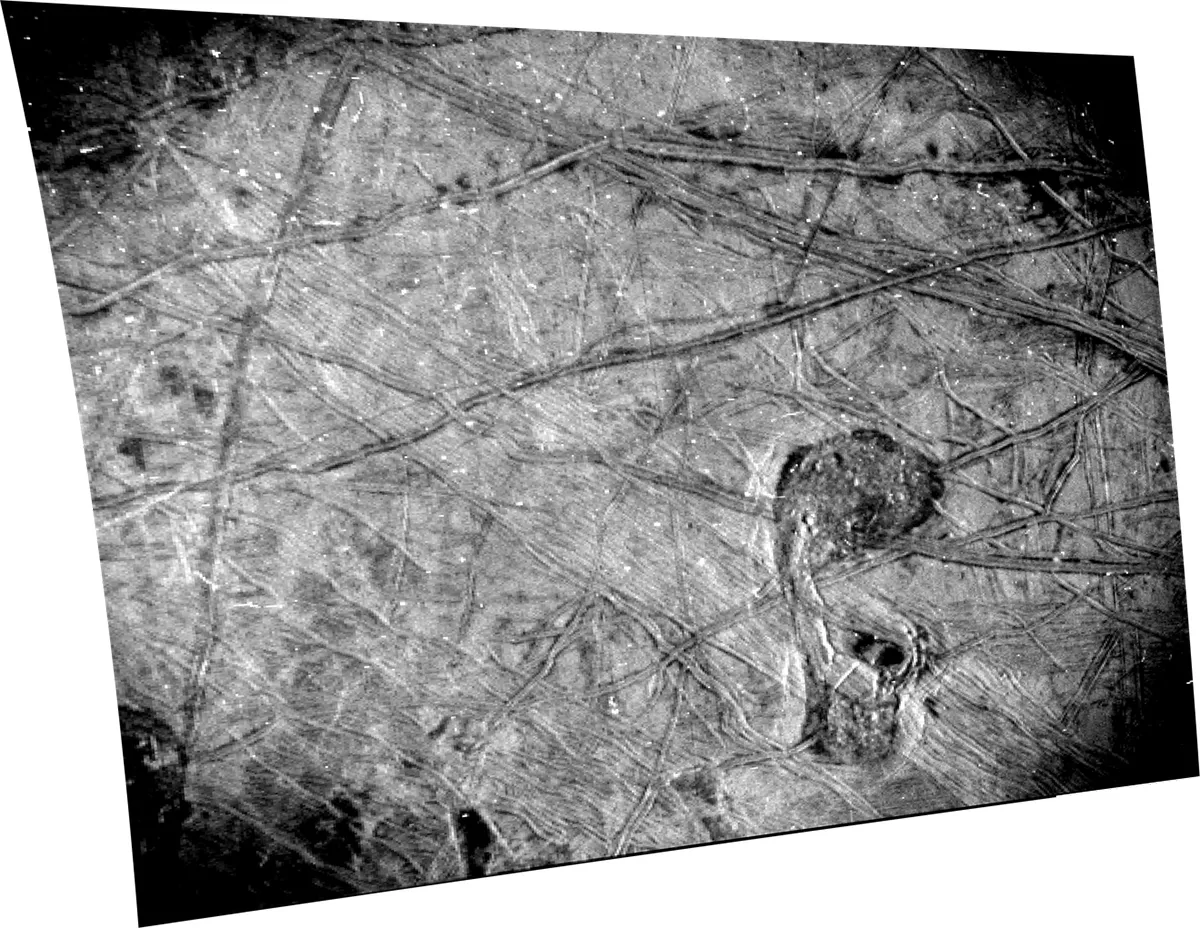

Image of the surface of Jupiter’s mooon Europa captured by the Stellar Reference Unit on NASA’s Juno spacecraft, 29 September 2022. Top right can be seen double ridges and dark stains that could indicate plumes activity. Bottom right is a feature nicknamed the ‘Platypus’. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI

Image of the surface of Jupiter’s mooon Europa captured by the Stellar Reference Unit on NASA’s Juno spacecraft, 29 September 2022. Top right can be seen double ridges and dark stains that could indicate plumes activity. Bottom right is a feature nicknamed the ‘Platypus’. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI

But the nature of life on Europa is tougher to pin down. Like deep-sea ecosystems on Earth, it could cluster around hydrothermal vents at the ocean’s floor.

If Europan life exists, it may be something like terrestrial ‘endoliths’ – tiny organisms that thrive in very hostile conditions, gathering resources for growth from rocks, minerals or corals.

Europan life may also be algae or bacteria free-floating in the ocean.

Solar irradiation of the surface ice might saturate the crust, infusing the ocean with oxygen and peroxide.

That raises an intriguing possibility: within 12 million years, Europa’s ocean could become as ‘oxygenated’ as ours – yielding optimum conditions for multicellular life.

Ganymede’s salt-lovers Jupiter’s icy moon Ganymede. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill

Jupiter’s icy moon Ganymede. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill

Candidates for habitability also include two of Jupiter’s other moons, Ganymede and Callisto.

Ganymede could have an ocean sandwiched between icy subsurface layers.

The Galileo probe found an ocean as salty as ours may reside 200km (125 miles) under the surface.

NASA’s Juno probe found various salts on its surface – hydrated sodium chloride, sodium bicarbonate and ammonium chloride – which ignited renewed excitement about life.

A view of Jupiter’s moon Callisto captured on May 2001. Could this heavily cratered moon host a salty ocean? Credit: NASA/JPL/DLR

A view of Jupiter’s moon Callisto captured on May 2001. Could this heavily cratered moon host a salty ocean? Credit: NASA/JPL/DLR

Meanwhile, Callisto may have a salty ocean 150–200km (90–125 miles) deep – microscopic halotolerant organisms could thrive there.

But with less internal heat than Europa, its credentials for life are limited. However, in its favour, Callisto’s surface has remained unaltered for billions of years.

This geochemical stability and greater distance from Jupiter’s lethal radiation belts makes Callisto a prime target for future human exploration.

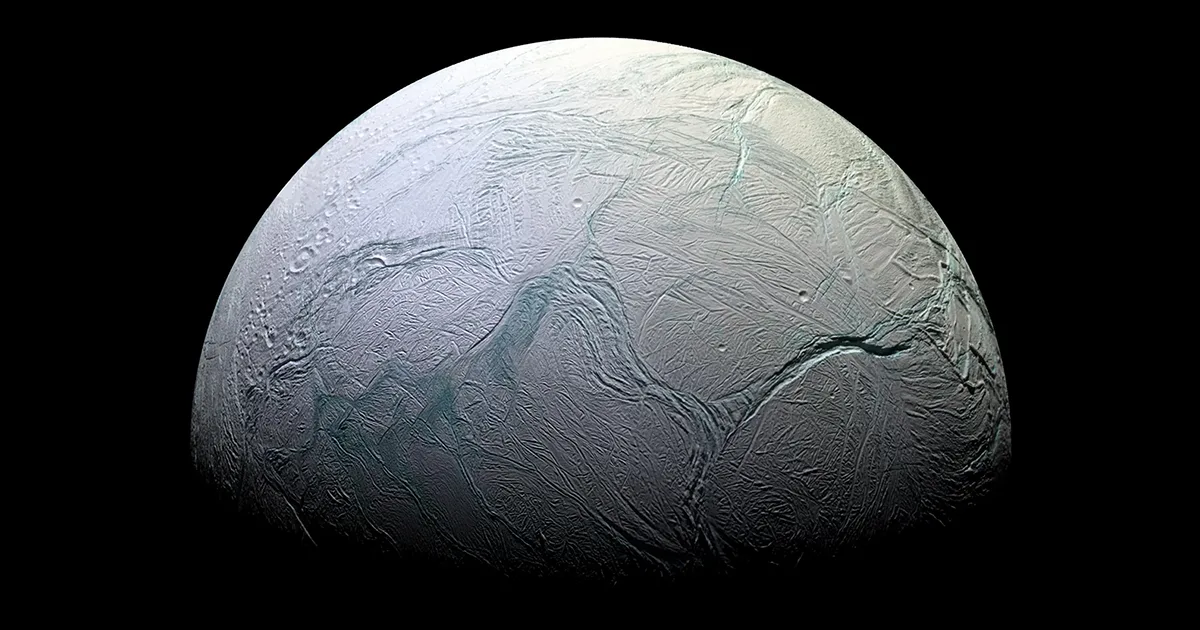

Ocean colonies on Enceladus Image of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Image of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

Saturn’s tiny moon Enceladus has a subsurface ocean and ongoing hydrothermal activity – both key enablers for life.

With a surface brighter than fresh snow and temperatures of –198°C (–324°F), internal activity is continually refreshing its surface.

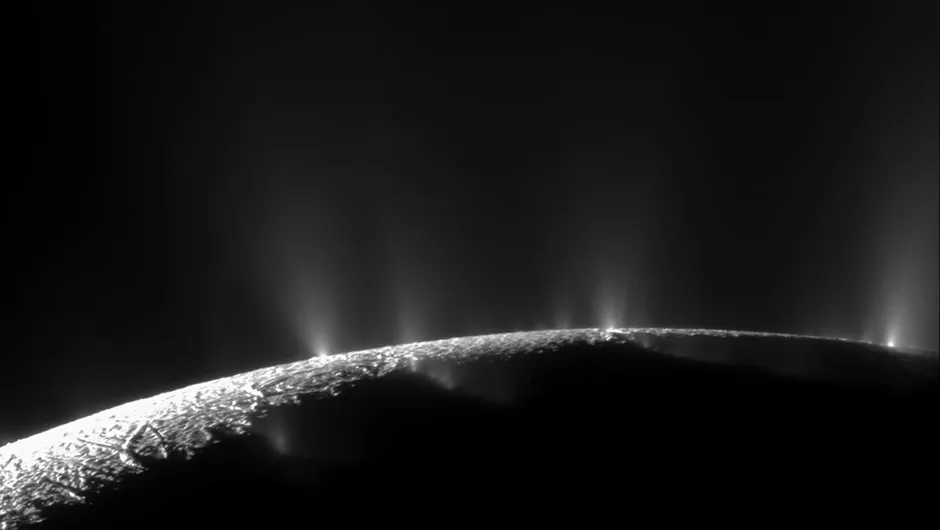

NASA’s Cassini probe observed water-rich plumes jetting from Enceladus’s south pole at velocities of 2,190km/h (1,360mph).

Recent estimates point to a subsurface ocean 10km (6 miles) deep. Cassini flew within 48km (30 miles) of Enceladus, directly through an erupting plume, revealing clues about the ocean.

This image captured by the Cassini spacecraft shows plumes of water ice erupting from the surface of Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

This image captured by the Cassini spacecraft shows plumes of water ice erupting from the surface of Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI

It discovered sodium and chlorine in the plumes, pointing to a salty ocean.

Later measurements confirmed molecular hydrogen in the plumes, a telltale sign of hydrothermal vent activity, and complex organic compounds that could form the basis of life.

If such vents exist, Enceladus’s interior could be as conducive to life as Earth: microbial communities might linger near the vents, perhaps using hydrogen and dissolved carbon dioxide in the water as an energy source.

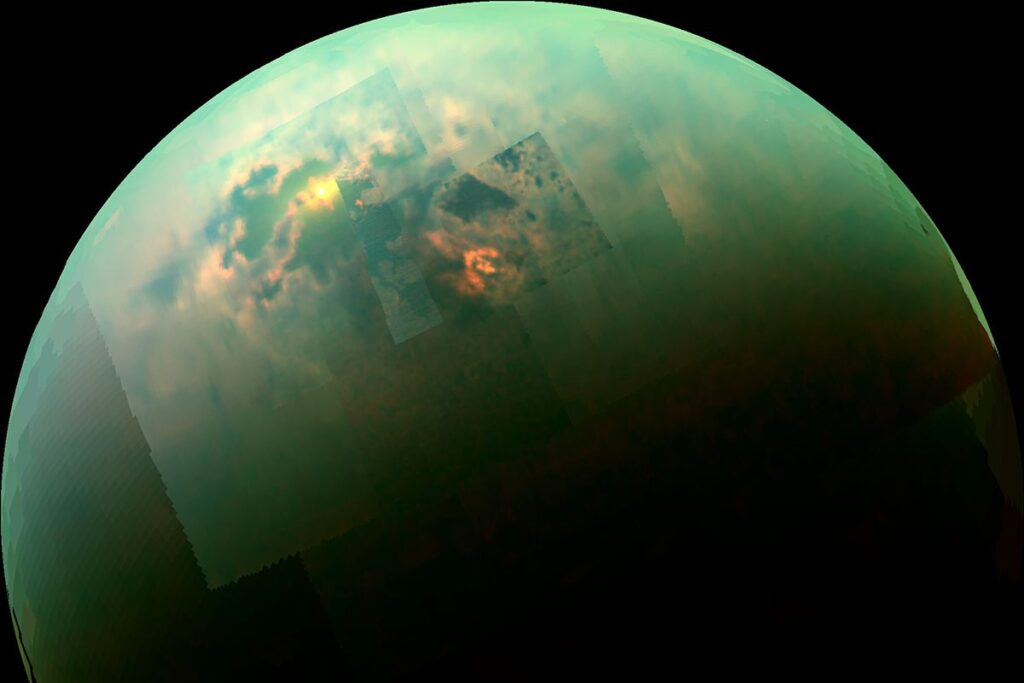

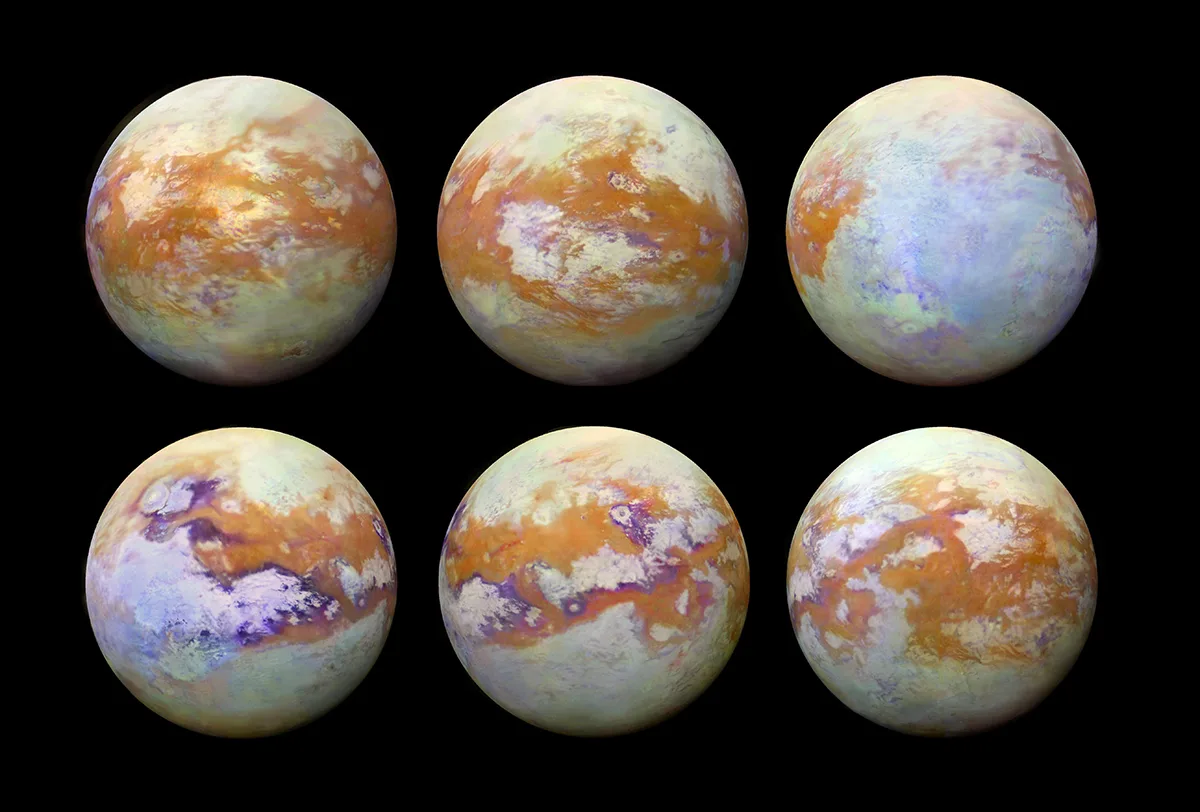

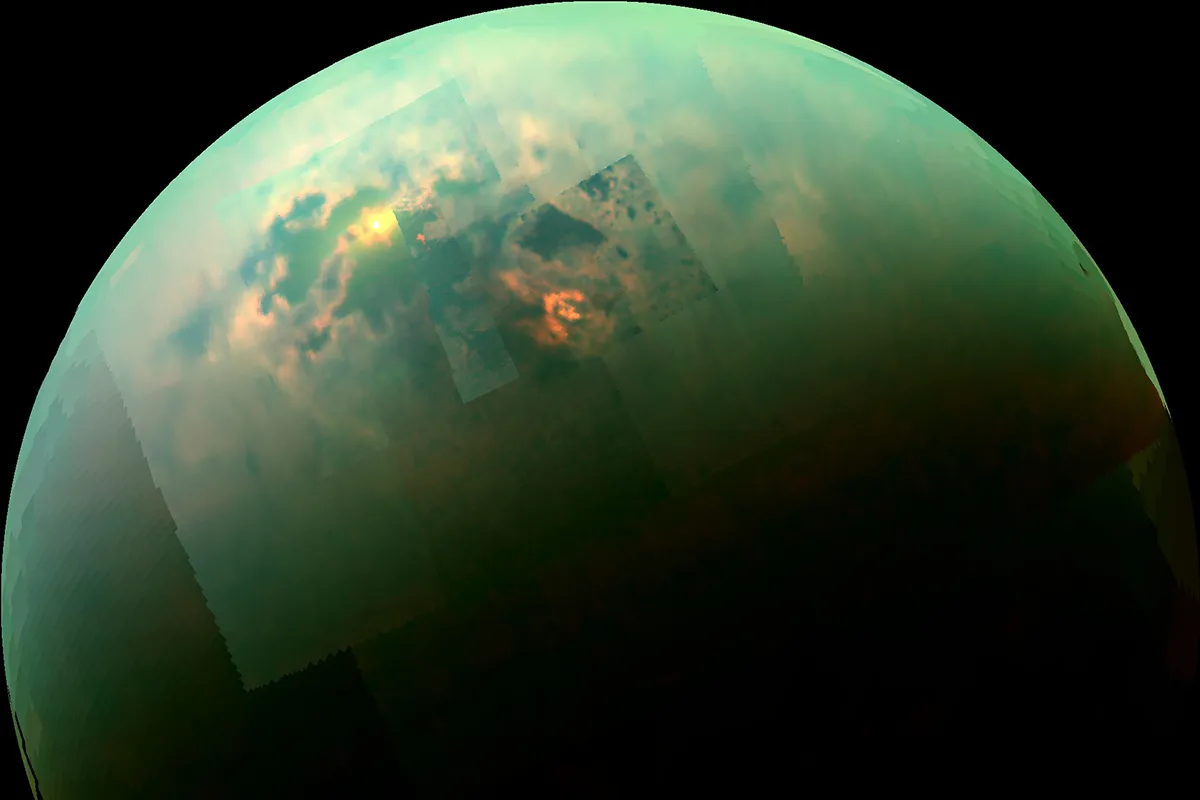

Titan’s methane-breathers Six infrared images of Saturn’s moon Titan captured by the Cassini spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Nantes/University of Arizona

Six infrared images of Saturn’s moon Titan captured by the Cassini spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Nantes/University of Arizona

Saturn’s moon Titan boasts an atmosphere similar in structure to Earth’s, albeit thicker, soupier and dominated by nitrogen.

Indeed, stable bodies of hydrocarbons on Titan’s surface may mirror what Earth was like before life evolved.

In 1980, the Voyager probes detected hydrogen cyanide (a key ingredient in amino acid synthesis), making Titan another moon of Saturn known to possess the building blocks of complex organic chemistry.

An infrared view of the Saturn moon Titan showing sunlight reflected off its polar lakes. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. Arizona/Univ. Idaho

An infrared view of the Saturn moon Titan showing sunlight reflected off its polar lakes. Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Univ. Arizona/Univ. Idaho

Titan may possess sufficient organic material to ignite a chemical evolution that mirrors the way life emerged on Earth.

Life could inhabit methane lakes with the same ease as terrestrial microbes favour water – inhaling hydrogen instead of oxygen, metabolising it with acetylene instead of glucose, and exhaling methane rather than carbon dioxide.

Titan’s –179°C (–290°F) surface temperature is probably too cold even for bacteria.

But five billion years hence, when the Sun expands into a red giant and consumes the inner rocky planets, including Earth, Titan may benefit from solar warming.

It could become a refuge for humans fleeing the devastation of the inner Solar System.

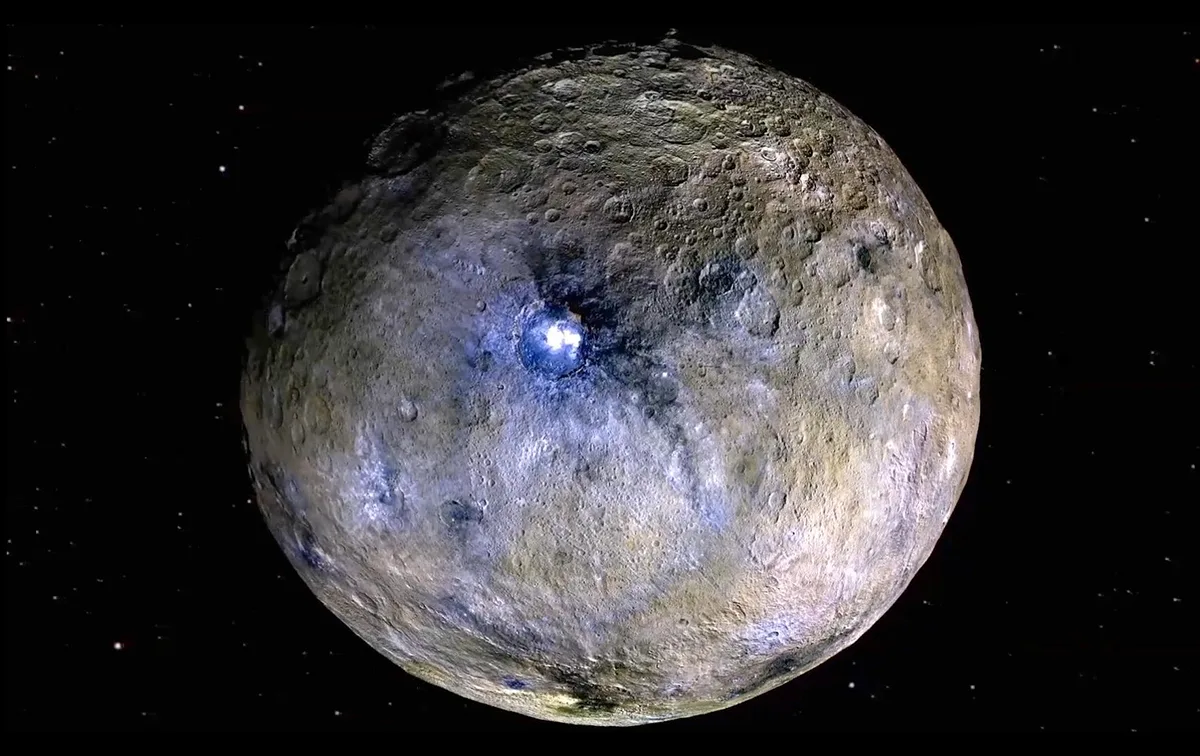

Brine-dwellers of Ceres Could Ceres once have hosted life in its liquid ocean? Image of the dwarf planet captured by NASA’s Dawn mission, showing the strange, bright deposits on its surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

Could Ceres once have hosted life in its liquid ocean? Image of the dwarf planet captured by NASA’s Dawn mission, showing the strange, bright deposits on its surface. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA

Other candidates for life include the dwarf worlds Ceres and Pluto. Ceres, in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, has a crust of ice, salts and hydrated minerals.

Briny subsurface ‘pockets’ could provide habitats for microbial life. Ceres is close enough to the Sun and has sufficient long-lived radioactive isotopes in its interior to keep water liquid for extended periods.

Image of Pluto captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL – NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute – https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/855/color-pluto/

Image of Pluto captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL – NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute – https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/855/color-pluto/

Pluto boasts water-ice mountains rising to 3,500 metres (11,000ft), their peaks peppered with methane frost.

The dwarf planet’s internal heat might sustain a subsurface water ocean 100km (60 miles) deep which may have been habitable in the distant past.

It might remain habitable today, under suitable conditions of internal warmth and low toxicity.

But at 5.9 billion kilometres (3.7 billion miles) from the Sun, the jury remains out on the question of life on Pluto.

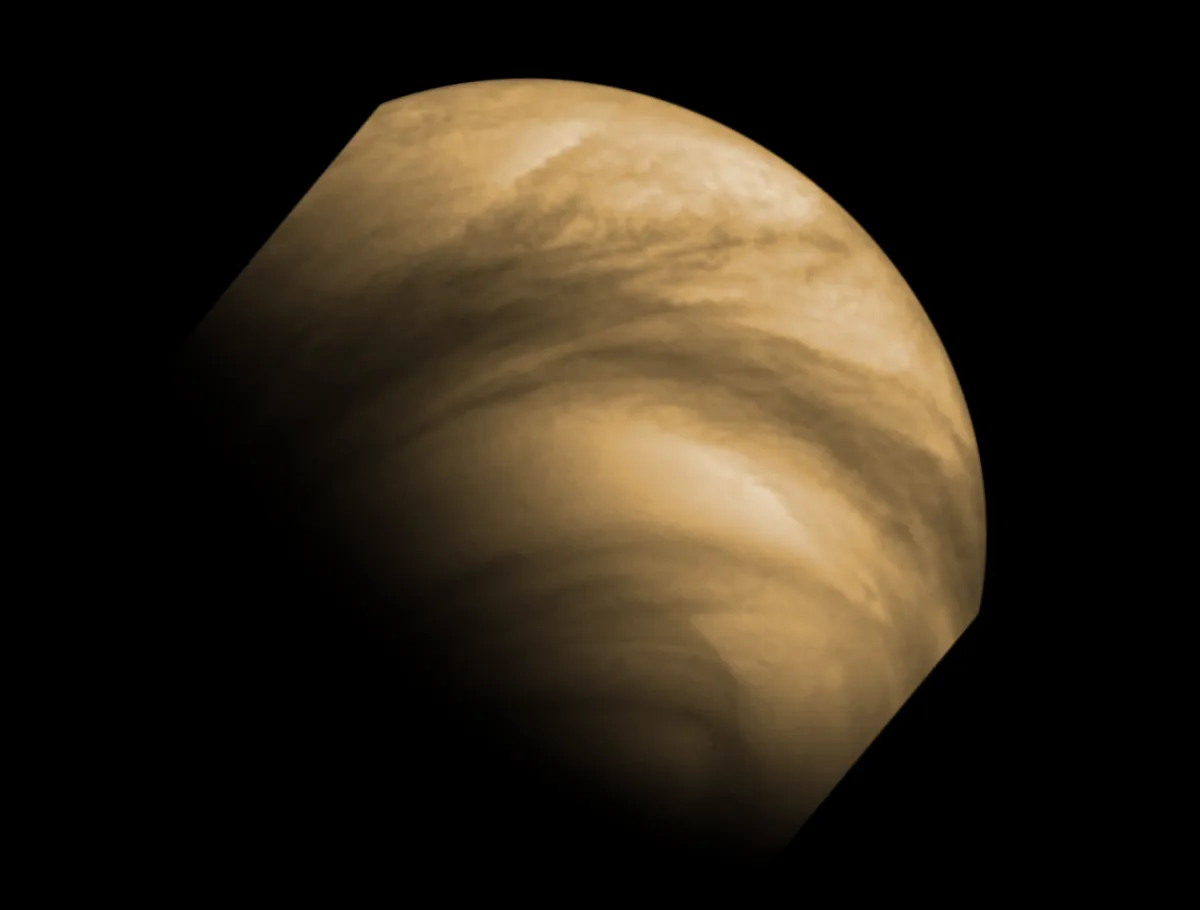

Acid-lovers above Venus A false-colour image of cloud tops captured by the Venus Express probe from a distance of 30,000km on 8 December 2011. Credit: ESA/MPS/DLR/IDA

A false-colour image of cloud tops captured by the Venus Express probe from a distance of 30,000km on 8 December 2011. Credit: ESA/MPS/DLR/IDA

Finally comes Venus, Earth’s closest planetary neighbour and near-twin in mass, size and surface gravity.

Dominated by a carbon dioxide atmosphere with thick sulphuric acid clouds, no liquid water, a runaway greenhouse effect, surface temperatures averaging 462°C (863°F) and pressures 92 times higher than on Earth, Venus is a hellish perversion of our world.

But it might not always have been this way. Venus perhaps had liquid water for 600 million years and

could have been habitable for three billion years – ample time for life to evolve.

Today’s surface temperatures are far beyond survivabe even for extremophile bacteria, but Venus’s upper atmosphere is another matter.

At 50km (30 miles) above the surface, temperatures around 30°C (86°F), pressures equal to those at terrestrial sea level and low solar radiation combine to produce relatively ‘Earthlike’ conditions.

Water, carbon dioxide and sunlight – essential for photosynthesis – are plentiful here, and the possibility that Venus may still be volcanically active gives a potential source of nutrients.

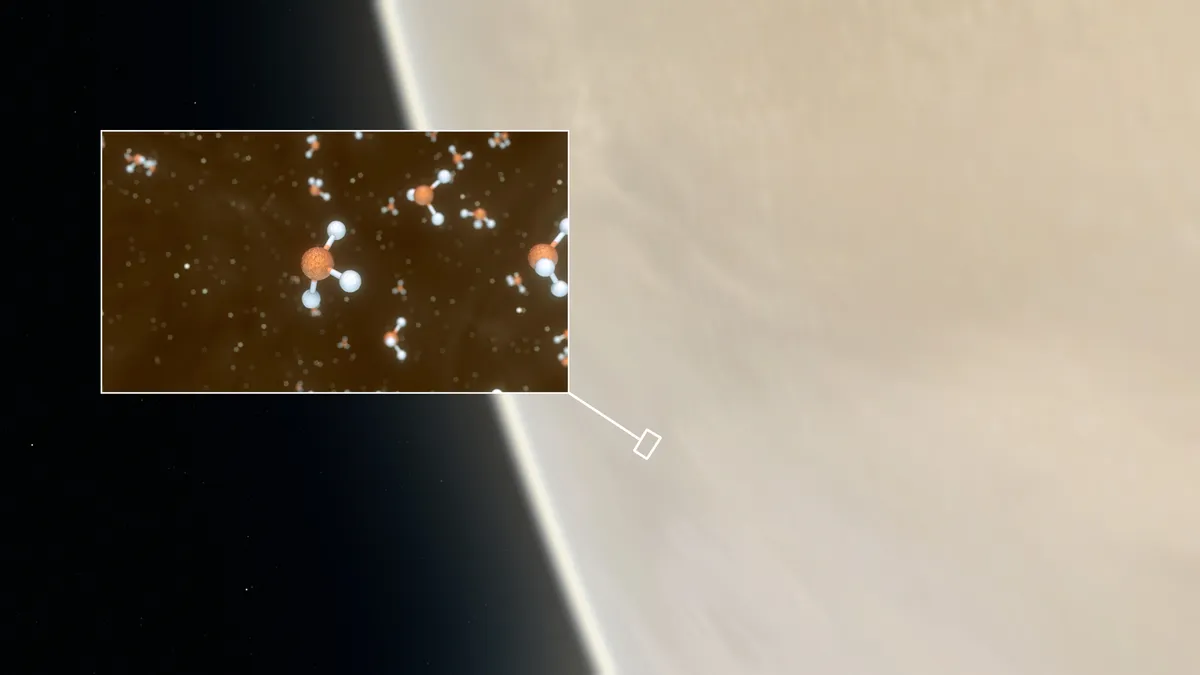

An artist’s impression of Venus, inset showing a representation of phosphine molecule. Credit: ESO / M. Kornmesser / L. Calçada & NASA / JPL / Caltech

An artist’s impression of Venus, inset showing a representation of phosphine molecule. Credit: ESO / M. Kornmesser / L. Calçada & NASA / JPL / Caltech

Phosphine, a potential ‘biomarker’ of life, was detected spectroscopically in 2020, although doubt has been cast on the find’s veracity.

But it remains possible that ‘thermoacidophilic’ extremophiles (organisms capable of growing under high temperatures and low pH levels) could thrive in Venus’s upper atmosphere.

For now, life is known to inhabit only one world: ours.

Here on Earth, it evolved in the unlikeliest of locations, in a million different ways, and to deal with the most extreme environmental stresses.

Life is a tough, durable and resilient thing. And if the right conditions exist there, it’s not unreasonable to suspect that life’s touchpaper may have been lit on another world beyond our own.