No audio available for this content.

News from the European Space Agency

Dedicated research and development, funded by European Union (EU) and European Space Agency (ESA) programs over the years, has played a key role in Galileo Second Generation.

Among the innovations that will benefit the new satellites are the development of new atomic clocks, links that allow the satellites to “talk” to one another in orbit and a prototype ground station that can precisely pinpoint satellites in the sky. These advanced technologies will ensure Galileo continues to provide world‑class positioning, navigation and timing to users worldwide.

The importance of R&D

Satellite navigation is constantly evolving, with new technologies being deployed. But before a technology can fly on a satellite, it must be derisked and qualified. This is where research and development (R&D) comes in, laying the groundwork for new technologies long before they see the light of day.

Horizon 2020 and Horizon Europe are R&D programs funded by the EU. A significant budget from these programmes is delegated to ESA for R&D to derisk new technologies for evolutions of Europe’s Galileo and EGNOS systems.

Complementing these EU R&D programs, ESA programs such as the General Studies Programme (now Discovery and Preparation), General Support Technology Programme and the former European GNSS Evolution Program (EGEP) have also performed R&D for future satellite navigation technologies.

R&D spurs the innovation that allows Galileo and EGNOS to modernise and develop new applications and services. Several activities funded through these programmes have contributed to Galileo Second Generation (G2). Some of these technologies will already fly on the G2 satellites when they are launched in the coming years.

New ways of keeping time

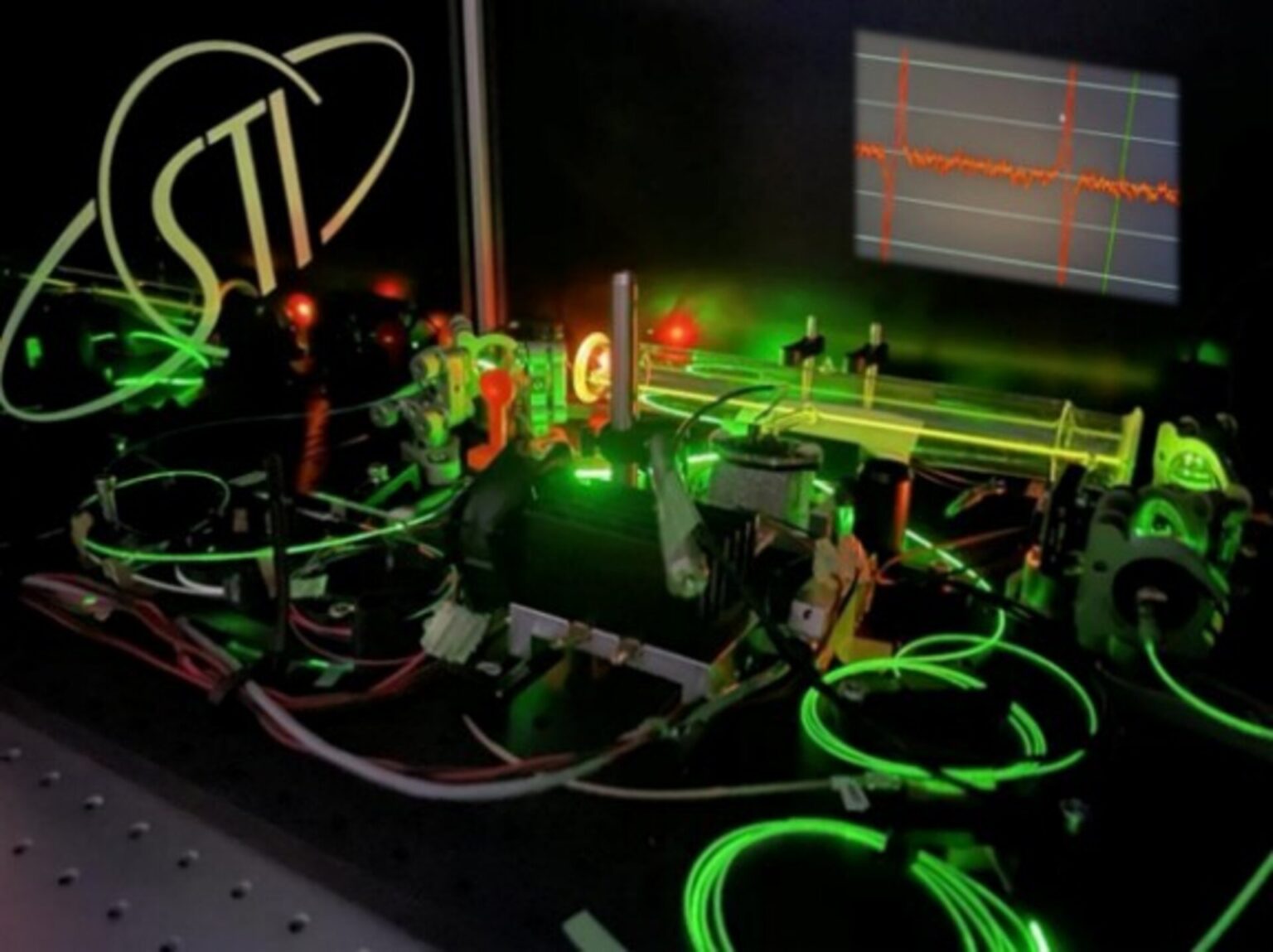

Galileo relies on highly precise onboard atomic clocks to ensure accurate global positioning and timing. Here, an iodine optical clock by SpaceTech, Germany (Credit: ESA)

Galileo delivers world-class positioning and timing, and its onboard clocks are the key to its performance. Each first generation Galileo satellite carries two passive hydrogen maser and two rubidium atomic frequency standard clocks. These clocks, developed by Leonardo and Safran Timing Technologies, respectively, are currently Galileo’s only space-qualified clocks.

A rubidium pulsed optically pumped (Rb POP) clock by Leonardo, Italy. (Credit: ESA)

To keep up with the latest technologies and allow for a broader diversity of European qualified clocks, R&D activities have encouraged European companies to develop new types of space-worthy atomic clocks. This investment is critical due to the time and expertise it takes to develop such complex and sensitive technologies. These activities aimed to develop alternative atomic clocks for Galileo that can improve performance and robustness and support Europe’s place as a leader in satellite navigation.

A Mercury ion clock (MIC) from Safran Timing Technologies, Switzerland. (Credit: ESA)

Seven innovative clock technologies were developed by European companies from France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland. After initial development activities, three of these clocks — proposed by Leondardo, SpaceTech and Safran Timing Technologies — were selected to progress to hardware development in preparation for a first flight.

Leonardo’s Rubidium Pulsed Optically Pumped clock is currently under development and planned to fly as an experimental clock on a Galileo Second Generation satellite. The Iodine Optical clock developed by SpaceTech is undergoing early development and shows potential for future use as an experimental clock on Galileo satellites. The Mercury Ion clock by Safran Timing Technologies recently launched its development activities.

Following an analysis of the clocks’ eventual in-orbit performance, a programme decision by the European Commission will be made before starting the operational phase of these new clock technologies.

Conversations in the sky

An intersatellite link transceiver by Thales Alenia Space. (Credit: ESA)

The Galileo system currently relies on links between satellites and ground stations to monitor and control the satellites and to determine the onboard clock skew. Clock skew occurs when a clock signal reaches different parts of a system at different times, which can cause errors in position calculations.

Galileo Second Generation will introduce inter-satellite links (ISL), allowing the satellites to ‘talk’ directly to one another in orbit. This will enable additional time synchronisation and ranging measurements that will improve knowledge of the satellites’ orbit and clock skew.

ISL will also allow faster data dissemination. If a particular satellite is not visible to a ground station, information can be sent to a different satellite and then passed on instead of waiting for the satellite to be visible.

An intersatellite link transceiver by Airbus Defence and Space. (Credit: ESA)

Two early models of ISL transceivers that are essentially identical to those which will fly on the Galileo Second Generation satellites were designed and developed. The transceivers, which can both send and receive signals, were developed by Thales Alenia Space (Spain) and Airbus Defence and Space (Germany).

One of these transceivers is about to enter the formal testing phase, while the other has undergone successful environmental qualifications. After the transceivers have completed their qualifications and testing, they will be ready for their trip to space.

Precisely pinpointing satellites

Accurate positioning, navigation and timing relies on knowing precisely where satellites are in their orbits. Galileo satellites are located by tracking their L-band antenna transmissions from the ground. Each satellite also has a laser retroreflector, which allows measurement of their orbit to within a few centimeters. Known as satellite laser ranging (SLR), this method measures the time it takes for a laser pulse to make the trip from a ground station, called an SLR station, to the satellite and back, then uses these measurements to determine the satellite’s orbit. Presently, SLR stations are owned and operated by scientific community users and serve multiple space missions.

One of the challenges of current SLR is the fact that the lasers are not safe for human eyes and cannot be used if an aircraft is flying nearby as the lasers could blind the pilots. This means SLR stations must coordinate with civil aviation and may not be allowed to use all parts of the sky. SLR stations also have limited availability due to local atmospheric conditions (clear skies are key), and low levels of automation (intensive need for human operators).

A prototype satellite laser ranging station in Matera, Italy. (Credit: ESA)

To mitigate these limitations, a modernized, eye-safe SLR station prototype for Galileo satellites has been developed by DiGOS (Germany) and commissioned in Matera, Italy. Due to the station design and laser wavelength used, there will be no need to coordinate with civil aviation. The station’s new technologies also explore increased automation using a predefined schedule to reach satellites. Although human operators are still needed, their workload is reduced.

A field campaign of the prototype SLR station is planned for this year as part of the Galileo Second Generation System Test Bed tasks. It will evaluate the potential benefits of SLR as a complement to L-band ground ranging. If the station is added to the Galileo ground segment, it could enhance the system’s robustness by providing an independent means of determining the satellites’ locations. In this case, interface design adjustments would need to be made to allow operational use of the station.

Beyond providing another method for determining Galileo satellite orbits, this station could also help contribute to the Galileo Terrestrial Reference Frame and could support ESA navigation scientific missions such as Genesis.