Europa has long stood out as a prime place to search for life beyond Earth, thanks to the global ocean hidden beneath its cracked ice shell. But water alone is not enough – life also needs energy.

A new modeling study suggests that energy may be scarce at Europa’s seafloor. The researchers found that the moon’s rocky interior is likely quiet and largely inactive beneath its deep ocean.

That calm seafloor would limit the chemical fuel available to support life today.

A team led by Dr. Paul Byrne at Washington University used computer models to explore a place no mission can yet reach.

The results help sharpen expectations for the upcoming Europa Clipper mission, guiding where scientists should focus the search for life.

An ocean without motion

On Earth, moving tectonic plates crack the ocean crust and keep seawater circulating through rock, altering minerals and releasing chemical energy.

That process fuels hydrothermal vents, where hot, chemical-rich water leaks into the ocean and supports dense communities of microbes.

Europa appears to lack that kind of active plate motion. Rare fault movement would slow those fresh chemical reactions, meaning any life there would need a different energy source.

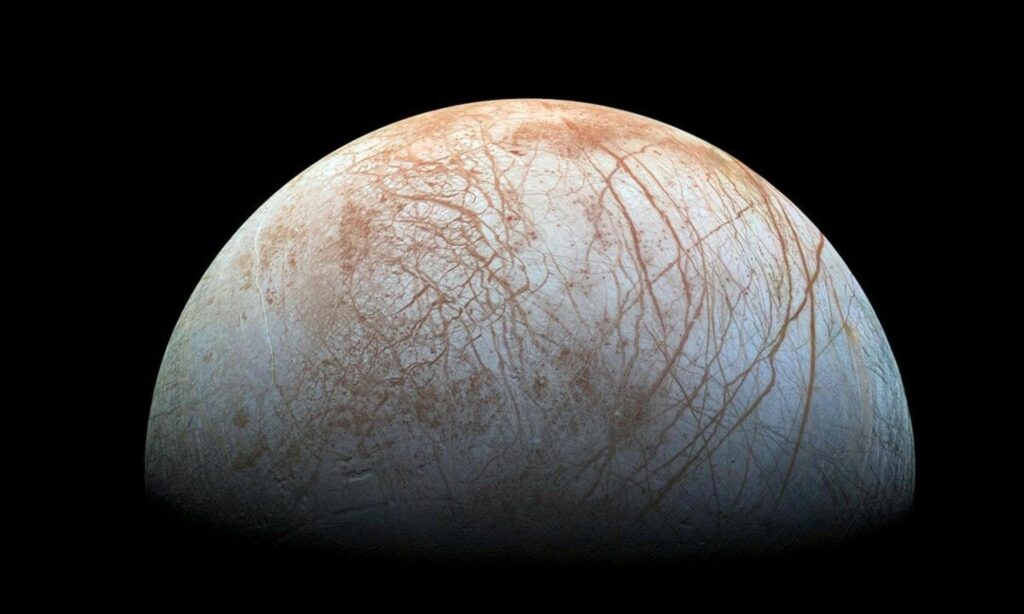

Surface images show Europa wrapped in a bright shell of ice, with strong evidence that a global ocean lies beneath it.

Scientists estimate the ice is about 9 to 16 miles thick (15 to 25 kilometers), sealing the water below.

Although Europa is slightly smaller than Earth’s Moon, NASA estimates it may hold roughly twice as much ocean water as Earth.

Europa’s cooling limits ocean life

Heat from a rocky interior can drive seafloor change, but Europa formed smaller than Earth and cooled more quickly.

Byrne’s team calculated that most of its internal heat escaped billions of years ago, leaving the deep ocean without a steady source of warmth.

Without that extra heat, the rocks below cannot keep recycling chemicals the way Earth’s active seafloor does.

Over time, rock and water tend to settle into balance, reducing the chemical mismatches that life can exploit.

Weak tides below the ice

Jupiter tugs strongly on its moons, and when an orbit stays slightly stretched, that pull can generate heat through tidal flexing.

The process, called tidal heating, turns gravitational stress into internal warmth. Io shows this effect dramatically, earning its reputation as the solar system’s most volcanically active world.

Europa, however, feels much gentler tides. Tests by the WashU team show that modern tidal stresses fall far below what even weak rock faults require, especially deeper than about 1,000 feet (300 meters).

As a result, today’s tides are unlikely to stir Europa’s seafloor.

Sealed rocks block chemistry

Even if Europa cracked more actively in the distant past, those fractures would not stay open forever. Minerals can slowly fill gaps and seal channels when water circulation slows or stops.

The study notes that fault surfaces tend to clog with newly formed material, which blocks water flow through rock and limits deeper contact between ocean water and fresh stone.

Once sealed, old fractures become poor plumbing, sharply reducing the supply of new chemical energy.

Is ocean life possible on Europa?

Some chemical reactions may still operate in the shallowest rocks, where ocean water can seep into small cracks over long periods.

Radiation-driven chemistry, known as radiolysis, could also split water molecules and generate hydrogen and other reactive compounds inside Europa’s rocky layer.

Those processes might support only sparse ecosystems and would likely leave faint chemical signatures.

Surface fractures and ridges show that Europa’s ice shell still shifts, occasionally opening pathways for salty water to rise or surface chemicals to sink.

The new stress calculations do not rule out activity entirely, but they reshape where scientists should search for it.

Europa Clipper, launched in October 2024, is now en route to Jupiter. According to NASA, the spacecraft will reach the system in April 2030 and begin repeated Europa flybys in spring 2031.

Its instruments cannot see directly through miles of ice, but they can detect magnetic, gravitational, and radar signals that hint at ocean depth, ice thickness, and possible zones of recent exchange.

Narrowing the search for life

Jupiter’s system holds nearly 100 moons, and scientists now recognize 95 of them. The moons range from barren rock to ice-covered worlds with complex geology.

Studies like Byrne’s help mission planners narrow their focus, prioritizing places where liquid water meets active rock – the kind of contact that can generate usable chemical energy.

Taken together, the new results suggest that Europa’s strongest chances for chemical energy may lie in shallow rocky zones or in regions where the ice shell actively exchanges material with the ocean below.

“I’m not upset if we don’t find life on this particular moon,” said Byrne.

Europa Clipper will help shrink the unknowns, but confirming any life would still require direct samples from the ocean itself.

The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI Institute

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–