Physicists are building detectors so sensitive that they may succeed in unraveling one of the greatest mysteries in modern science: the true nature of dark matter.

The portions of the universe visible to us comprise about 5% of what exists, with the remaining 95% composed of mysterious, non-luminous material called dark matter. Although its existence can be inferred from its influence on visible matter throughout the cosmos, direct detection of this mysterious yet prolific substance remains elusive.

“The challenge is that dark matter interacts so weakly that we need detectors capable of seeing events that might happen once in a year, or even once in a decade,” says Dr. Rupak Mahapatra, an experimental particle physicist at Texas A&M University.

To overcome such challenges, Mahapatra and his colleagues are now designing dark matter detectors that are more sensitive than any ever built by scientists, which they say could detect even the faintest signals produced by particles that seldom interact with ordinary matter in our universe.

Dark Cosmic Mysteries

Mahapatra specializes in the design of advanced detectors that incorporate semiconductors and cryogenic quantum sensors, which he and his colleagues say are pushing the boundaries of the search for dark matter.

Like dark matter, its evasive counterpart—dark energy—drives the accelerating expansion of our universe. While dark matter is like an invisible cosmic glue that holds everything we can perceive together, dark energy behaves almost like an unseen cosmic wind that is forcing everything apart.

Yet, despite their profound influence on the cosmos, neither of these abundant “dark” influencers can be directly perceived, since they produce no light of their own, nor do they reflect the luminosity of other light sources in our universe. Still, their gravitational influence is undeniable and plays a significant role in the shaping of celestial features at massive cosmic scales.

The Next Generation of Dark Matter Detectors

Mahapatra and his colleagues were instrumental in developing TESSERACT, a highly sensitive dark-matter detector. Fundamentally, such detectors aim to boost signals that, according to Mahapatra, have long remained “buried in noise.”

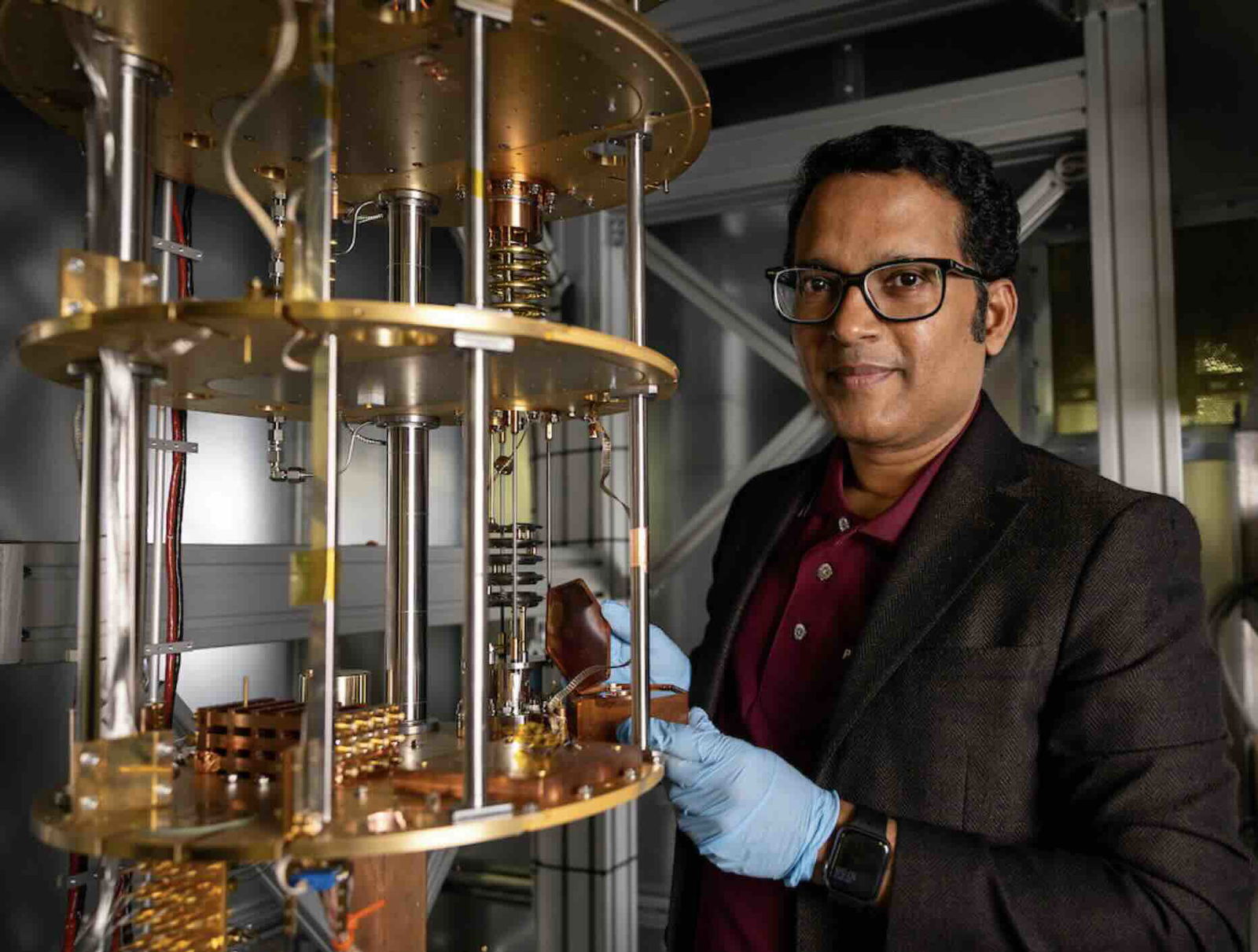

Above: Mahapatra with an R&D detector mounted in a dilution fridge that cools it to 100,000 times cooler than room temperature (Image Credit: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications)

Above: Mahapatra with an R&D detector mounted in a dilution fridge that cools it to 100,000 times cooler than room temperature (Image Credit: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications)

Experiments like TESSERACT, as well as the Super Cryogenic Dark Matter Search (SuperCDMS), rely on extremely sensitive detectors that operate at temperatures so cold that they approach absolute zero, allowing rare interactions between hypothetical particles and ordinary matter to potentially be detected.

In 2014, Mahapatra and his colleagues’ participation in SuperCDMS experiments focused on detection methods based on voltage-assisted calorimetric ionization, which led to a breakthrough in detecting a primary candidate for dark matter: low-mass, weakly interacting massive particles, or WIMPs.

WIMPS and the Quest for Dark Matter

Among the most promising potential candidates for dark matter, these hypothetical particles are extremely difficult to detect since their interactions occur through the weak nuclear force and gravity. However, if their existence were confirmed, they could hold the key to unraveling the mystery of all the missing mass in our universe.

Doing so is easier said than done, however. One challenge WIMPs pose is that their influence may be so subtle that they pass through our planet without leaving any discernible traces. Because of this, it could take years to assemble enough data to corroborate even a single WIMP’s transit through our planet.

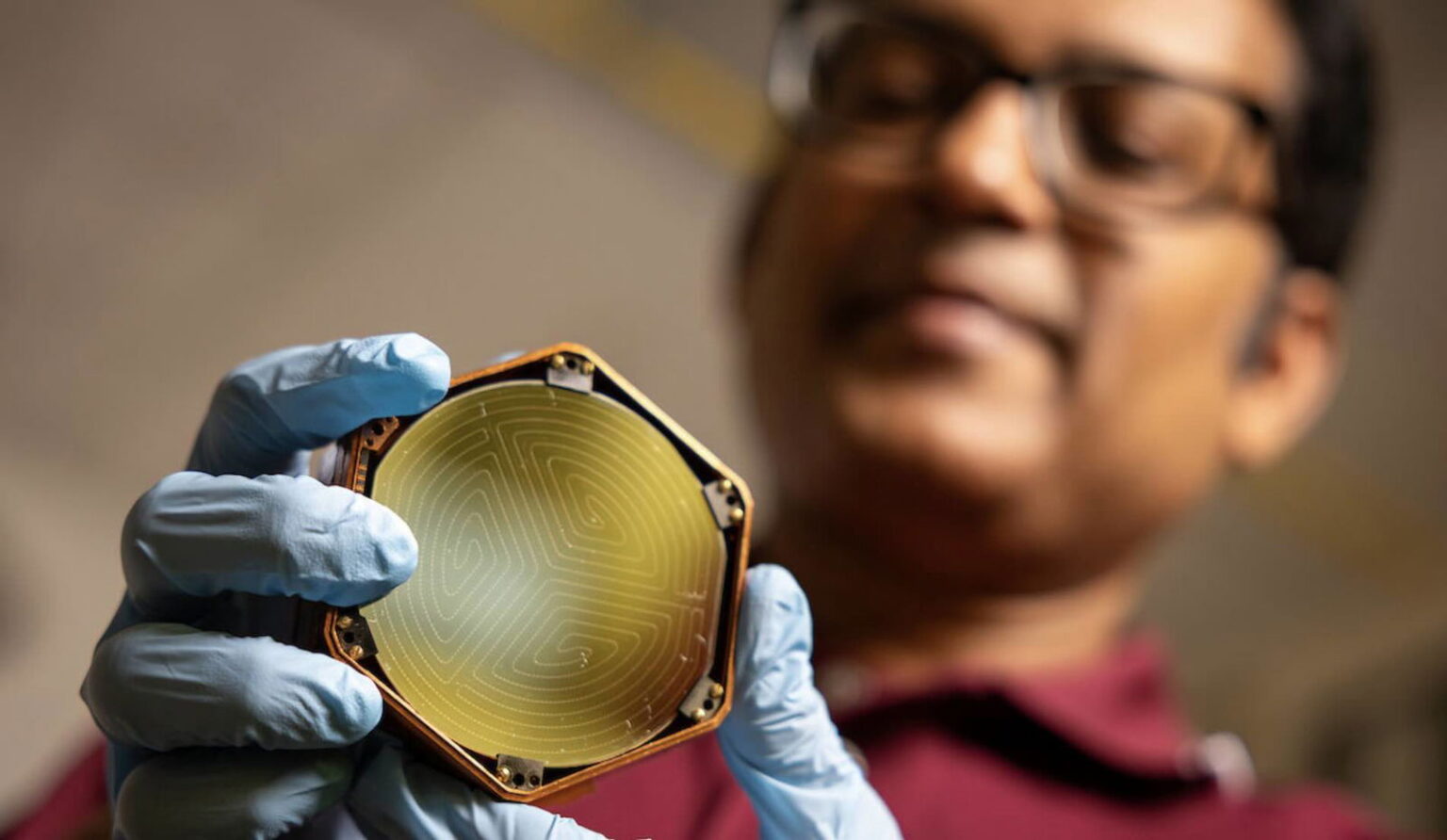

The image above shows a MINER detector developed by Mahapatra and his colleagues at Texas A&M University. This detector is ideal for searching for low-energy neutrinos, a process currently underway at the Texas A&M TRIGA reactor (Image Credit: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications).

The image above shows a MINER detector developed by Mahapatra and his colleagues at Texas A&M University. This detector is ideal for searching for low-energy neutrinos, a process currently underway at the Texas A&M TRIGA reactor (Image Credit: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications).

For Mahapatra, collecting that kind of data will likely require multiple approaches and a range of experiments.

“No single experiment will give us all the answers,” Mahapatra recently said, adding that “We need synergy between different methods to piece together the full picture.”

However, Mahapatra and his colleagues know that the payoff could mean a fundamental reshaping of our understanding of the cosmos and the forces that hold it together.

“If we can detect dark matter, we’ll open a new chapter in physics,” Mahapatra says. “The search needs extremely sensitive sensing technologies and it could lead to technologies we can’t even imagine today,” the physicist added.

Mahapatra and his colleagues’ most recent work, funded by the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Department of Energy, was featured in a peer-reviewed paper in Applied Physics Letters.

Micah Hanks is the Editor-in-Chief and Co-Founder of The Debrief. A longtime reporter on science, defense, and technology with a focus on space and astronomy, he can be reached at micah@thedebrief.org. Follow him on X @MicahHanks, and at micahhanks.com.