A NASA rover has used its last drop of a special chemical to analyze a Mars sample that may contain organics, the kinds of molecules life uses on Earth.

After the Red Planet reemerged from conjunction — a period when NASA doesn’t communicate with spacecraft because Mars is behind the sun from Earth’s point of view in space — scientists began planning a rare type of experiment for the Curiosity rover. The robot has only conducted it once before in the 13 years it has roamed Mars.

The experiment involves a solvent, called tetramethylammonium hydroxide, or TMAH in methanol for those with short attention spans. That liquid is mixed with powdered rock to make it easier to detect certain molecules, carbon-based compounds that could be linked to living things.

Curiosity’s onboard lab has only carried two small containers of this particular chemical for its entire mission, and one was already used nearly six years ago.

“We want to be very certain that everything will go well,” said Alex Innanen, an atmospheric scientist at York University in Toronto, in a mission log. “We did a rehearsal of the handoff of the sample.”

The powerful testing technique offers scientists a chance to look more closely for hints of life that standard tests might miss. Finding these molecules helps researchers piece together whether Mars once had conditions to support life and how earthly chemistry can arise in other worlds.

SEE ALSO:

No guarantees: Inside the biggest risks facing NASA’s Artemis 2 crew

Scientists have previously found organics on Mars, but they’re still working to understand what those detections mean. In September, NASA announced a sample collected by Curiosity’s younger sibling, the Perseverance rover, contains fossilized material that ancient microorganisms could have created.

“This finding by our incredible Perseverance rover is the closest we’ve actually come to discovering ancient life on Mars,” said Nicky Fox, NASA’s associate administrator. But officials have cautioned they can’t rule out other non-biological explanations for what they’ve found.

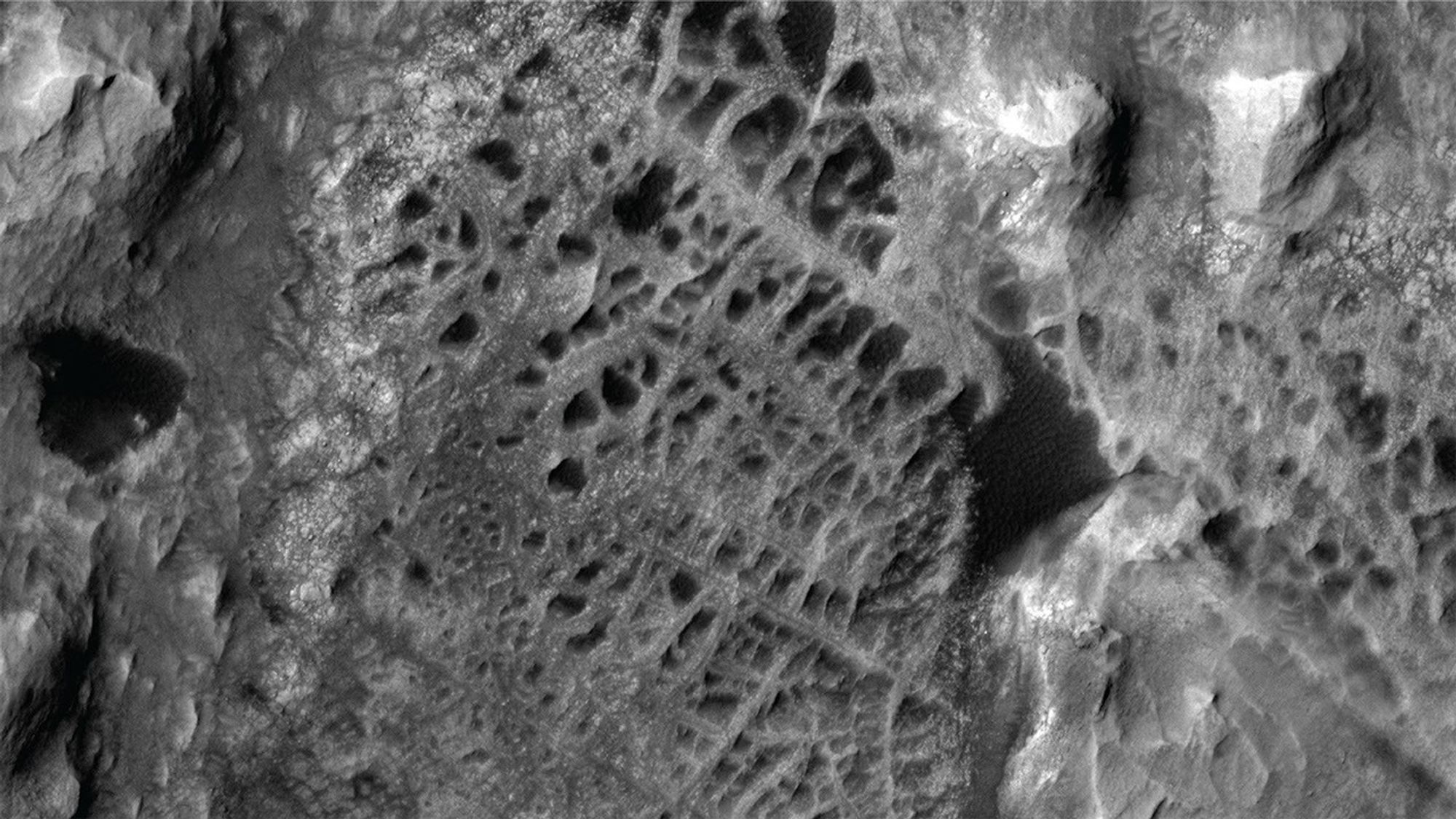

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has taken pictures of boxwork ridges on the Red Planet that Curiosity is now exploring up close on the ground.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / University of Arizona

Curiosity gathered its sample from a site near a hole drilled in November. That spot, dubbed Nevado Sajama, has fine-grained sedimentary rock thought to have formed long ago in conditions involving water. That makes it a good place to look for traces of fossilized organic material: Where there’s water, there’s potential for life — at least the kind scientists know about.

Mashable Light Speed

To reduce the risk of mistakes, the team practiced the steps for transferring a rock sample into Curiosity’s chemistry lab prior to the real drill. The rover began the experiment on Monday, Feb. 2, said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s project scientist.

The last time NASA soaked a sample in TMAH, Curiosity had drilled a hole in a clay-rich rock site, called Mary Anning. It took the team about seven months to interpret the results, which revealed more kinds of organic molecules in the rock than simple heating would have found. The findings gave scientists a better look at the complex chemistry in Gale Crater, though they continue to study whether some of those molecules could have come from the rover’s own instruments.

After that first test in 2020, scientists at Goddard Space Flight Center decided to redesign the experiment to account for some of the ways the solvent interacted with the Martian sediment and to make it even more like experiments scientists would run in labs on Earth, Vasavada said. The new method breaks the experiment up into a three-stage process, letting the solvent interact with the sediment at different temperatures.

The redesign took a few years to figure out in testbeds, in part delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. Once it was finalized, the rover team waited for the right opportunity. When Curiosity discovered clay minerals in the boxwork region, scientists thought this might be the time. Clay minerals can help protect organic material.

“That discovery, along with other favorable signs from the initial drill hole at the Nevado Sajama site, convinced the … mission that this was the right place to run the final TMAH experiment,” Vasavada said.

Since it launched in 2011, Curiosity, a Mini Cooper-sized robot on six wheels, has traveled over 352,000,022 miles: 352 million flying through space and another 22.5 rambling through the Martian desert.

For the past year, Curiosity has explored a mysterious Martian region that spans miles. Called a boxwork, the landscape features a network of low ridges that look like spiderwebs from orbit.

Scientists have suggested the boxwork could have formed with the last trickles of groundwater in the area before drying out for good, leaving behind minerals. But researchers need to know more about the fluids that penetrated the ridges.

Out of 74 cups inside Curiosity, nine of them had solvents for “wet chemistry” when it landed in 2012. Though the rover is now all tapped out of TMAH, it still has cups of another solvent. That chemical has an even longer name — seriously long — but you can call it MTBSTFA for short.

Two of the three phases of the latest experiment have already run, Vasavada said.

“We’re really excited about seeing the results,” he said. “These are quite complex analyses to interpret and understand, so it will take a few months for the team to be confident in knowing what they’ve found.”