A recent study published in PLOS One has revealed a groundbreaking discovery: the toxic chemicals found in Mars’s dirt could potentially be used to build the infrastructure necessary for sustaining human life on the Red Planet. This exciting research, led by scientists at the Indian Institute of Science and involving collaboration with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), has demonstrated how bacteria can help turn Martian soil into durable building materials. If this research proves successful, it could significantly alter the way we approach Mars colonization by allowing astronauts to use local resources, also known as in situ resource utilization, for constructing habitats.

How Toxic Martian Dirt Could Turn Into Building Blocks for Human Habitats

The idea of using Martian soil to build sustainable habitats on Mars has long been a topic of interest for space exploration experts. The notion of utilizing local resources, known as in situ resource utilization, is not new, but a recent study has taken this idea to a whole new level. Researchers found that a bacteria species called Sporosarcina pasteurii, typically found in Earth’s soil, could help bind Martian regolith into solid brick-like materials. This process is crucial for long-term missions on Mars, where astronauts cannot rely on supplies from Earth. As Shubhanshu Shukla, astronaut and co-author of the study, emphasized,

“The idea is to do in situ resource utilization as much as possible. We don’t have to carry anything from here; in situ, we can use those resources and make those structures, which will make it a lot easier to navigate and do sustained missions over a period of time.”

This research is a significant step toward creating a self-sustaining Martian base, and the use of local materials could reduce the enormous costs and risks of transporting construction supplies from Earth. By using regolith, the loose dust and rock found on Mars, along with the help of bacteria, astronauts could construct shelters for protection against the harsh Martian environment.

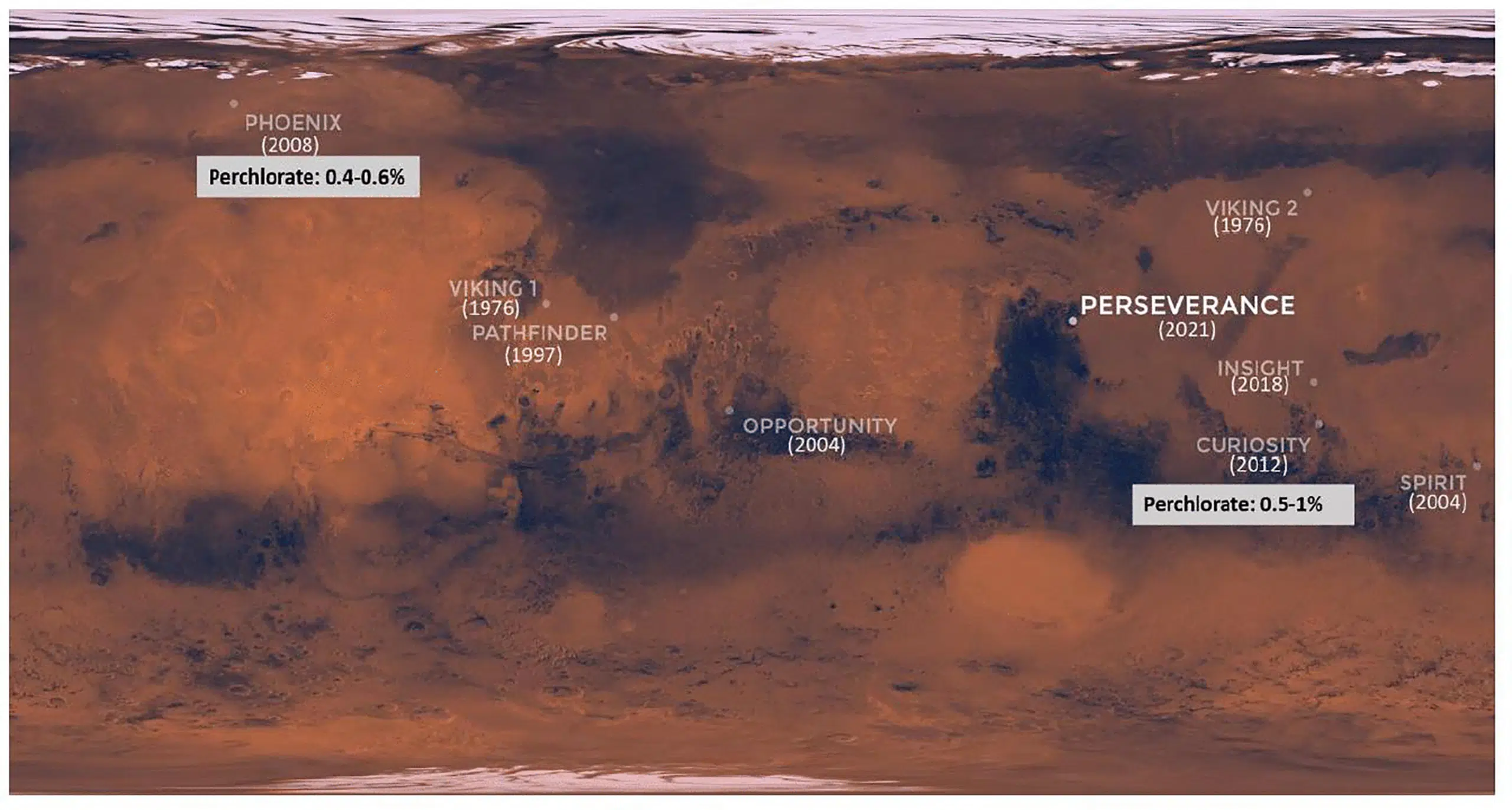

Map showing the landing sites for landers sent by NASA for Mars exploration.

Map showing the landing sites for landers sent by NASA for Mars exploration.

The respective landing years are mentioned in brackets. The Mars visit which found perchlorate on the Martian surface is highlighted. Mars map adapted from NASA-JPL/Caltech. (PLOS One)

Perchlorate: A Toxic Challenge and Unexpected Ally in Building Mars Structures

One of the key components in Martian soil is a compound called perchlorate, a chlorine-based chemical that is toxic to humans and can complicate life support systems on Mars. However, the recent study demonstrated that perchlorate may actually play a beneficial role in the production of building materials on Mars. While its toxicity presents a challenge for human habitation, scientists found that when perchlorate was introduced into the bacterial experiment, the bacteria reacted in an unexpected way.

In their experiment, researchers found that the perchlorate caused stress to the Sporosarcina pasteurii bacteria, which in turn triggered the bacteria to excrete additional proteins. These proteins helped form stronger, more durable bricks by creating calcium carbonate crystals that bonded the regolith particles together.

“When the effect of perchlorate on just the bacteria is studied in isolation, it is a stressful factor,” said microbiologist Swati Dubey, another co-author of the study. “But in the bricks, with the right ingredients in the mixture, perchlorate is helping.”

This discovery, published in PLOS One, suggests that, rather than hindering the biocementation process, perchlorate may actually improve the strength of the building materials. The bacterium forms tiny “microbridges” between the bacteria and the soil particles, further enhancing the material’s durability and making it a viable option for construction on Mars.

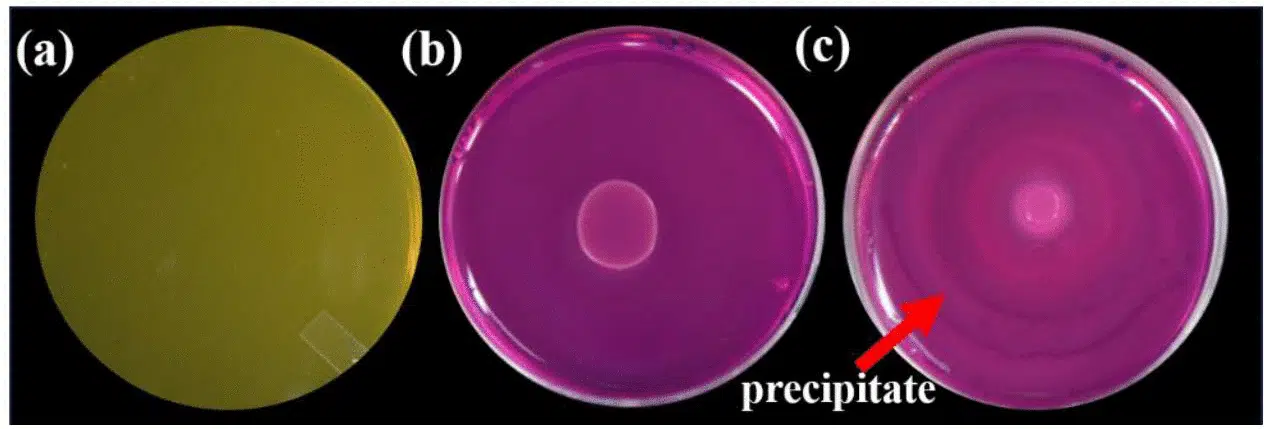

Phenol Red plate Assay for SI_IISc_isolate (also called SI) to test for ureolysis activity.(a) Control_ No bacteria on SMU + 0.001% Phenol Red Dye. (b) SI spot inoculated on SMU + Dye. The colour change from yellow to pink represents the pH change of the media from ~5.5 to.8 and above. (c) SI spot inoculated on SMU + Dye + 25mM CaCl2. The white lines on the plate represent calcite precipitate. Note: Plate dimensions- 90x14mm. (PLOS One)

Phenol Red plate Assay for SI_IISc_isolate (also called SI) to test for ureolysis activity.(a) Control_ No bacteria on SMU + 0.001% Phenol Red Dye. (b) SI spot inoculated on SMU + Dye. The colour change from yellow to pink represents the pH change of the media from ~5.5 to.8 and above. (c) SI spot inoculated on SMU + Dye + 25mM CaCl2. The white lines on the plate represent calcite precipitate. Note: Plate dimensions- 90x14mm. (PLOS One)

Biocementation: A Step Towards Mars-Based Construction Using Local Resources

The process used to create these bricks is called biocementation, where bacteria help in binding soil particles into a solid mass. The bacteria excrete proteins that react with the minerals in the soil, forming crystals that act like natural cement. The recent study explored how the addition of nickel chloride and guar gum, a natural adhesive, improved the binding process, making it even stronger. This combination of biological and chemical reactions results in a brick-like material that can withstand the harsh conditions of Mars.

A significant breakthrough in this study was the bacteria’s ability to adapt to the Martian environment, even with the added challenge of perchlorate in the soil. The bacteria’s response to stress, though seemingly negative, actually helped form stronger materials. According to Shubhanshu Shukla, the goal of this research is clear:

“We don’t have to carry anything from here; in situ, we can use those resources and make those structures.”

The ability to utilize Martian regolith, along with the bacteria’s biocementation process, opens up new possibilities for sustainable living on Mars.

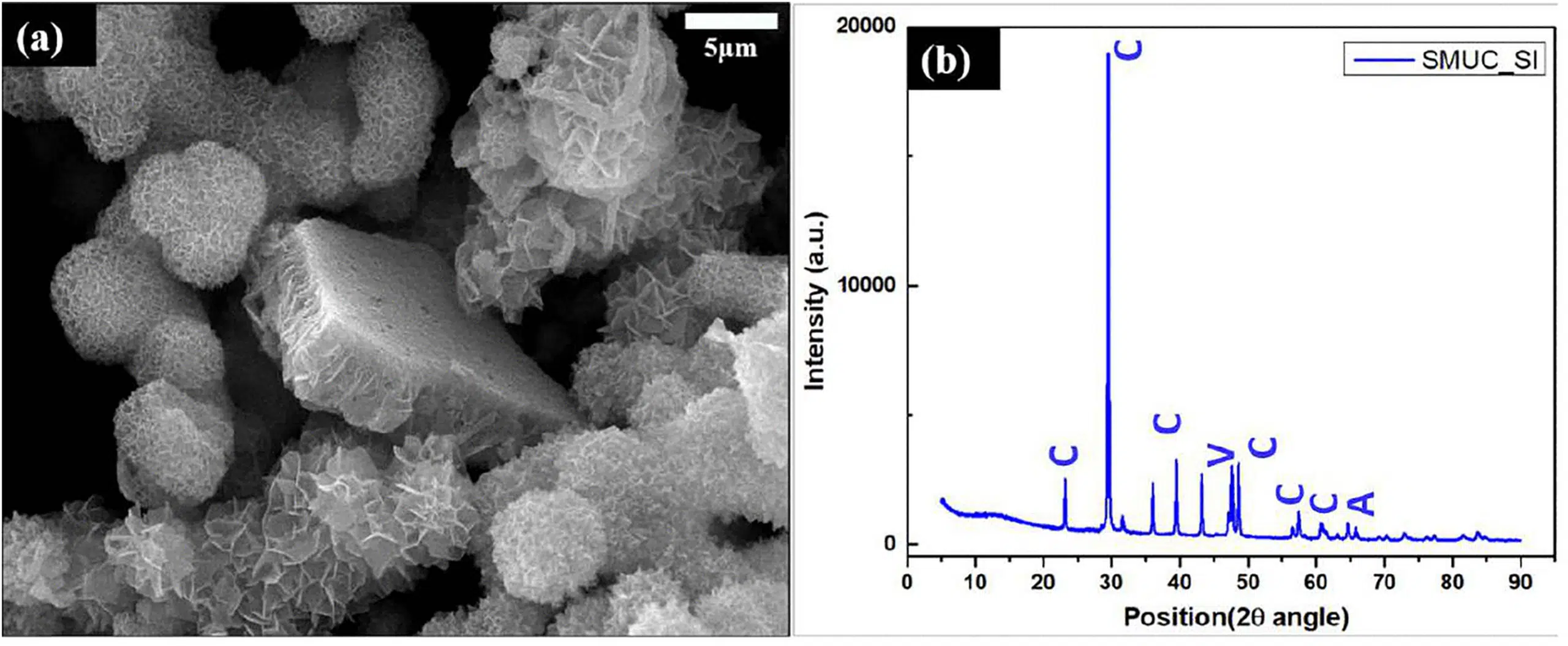

(a) Scanning Electron Microscopy images of the calcite precipitate made by the MICP-capable bacteria SI via its ureolytic activity. (b) X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) results for the precipitate. C represents Calcite, V represents Vaterite, A for aragonite, and peaks as identified through the ICSD database sub-file.

(a) Scanning Electron Microscopy images of the calcite precipitate made by the MICP-capable bacteria SI via its ureolytic activity. (b) X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) results for the precipitate. C represents Calcite, V represents Vaterite, A for aragonite, and peaks as identified through the ICSD database sub-file.

(PLOS One)

Testing Mars Building Techniques in Earth-like Conditions

To understand how this biocementation process would work on Mars, the researchers had to simulate Martian soil conditions as closely as possible. While samples of real Martian regolith are not yet available, the researchers used a simulant known as Mars Global Simulant 1, which mimics the properties of actual Martian soil. However, this simulant is missing one crucial component: perchlorate. For the experiment to more accurately reflect conditions on Mars, the researchers carefully introduced perchlorate into the simulant and observed its effect on the bacteria.

The results were promising, and now the researchers are looking to further test the biocementation process under Mars-like conditions, including the planet’s carbon dioxide-rich atmosphere. The next phase of research will focus on how this method can work in a simulated Martian environment, taking into account factors such as low temperatures, radiation, and limited resources. As Aloke Kumar, study co-author, explained, “Mars is an alien environment. What is going to be the effect of this new alien environment on Earth organisms is a very, very important scientific question that we have to answer.”