Back in 2013, I was living in North London with my best friend and two Italian dudes. One evening, Wendy, the best friend in question, found me staring out of the window.

She asked what had me so transfixed. It was, of course, the Moon. Sometimes, especially when it’s full, I just look up at our beautiful natural satellite and can’t stop staring.

The longer I look, the more detail I see.

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI)

Here’s an embarrassing fact: not only do I not own a telescope, but I didn’t even look at the Moon through one until October 2021.

I was heading to the North Yorkshire Moors in the UK for a weekend away and borrowed a lovely 10-inch Dobsonian from the University of Birmingham’s student astronomical society.

I set it up outside the holiday cottage, looked at the Moon… and was overwhelmed.

In fact, I was so stunned that I called over total strangers who were relaxing outside their own holiday cottages and got them to look at it too.

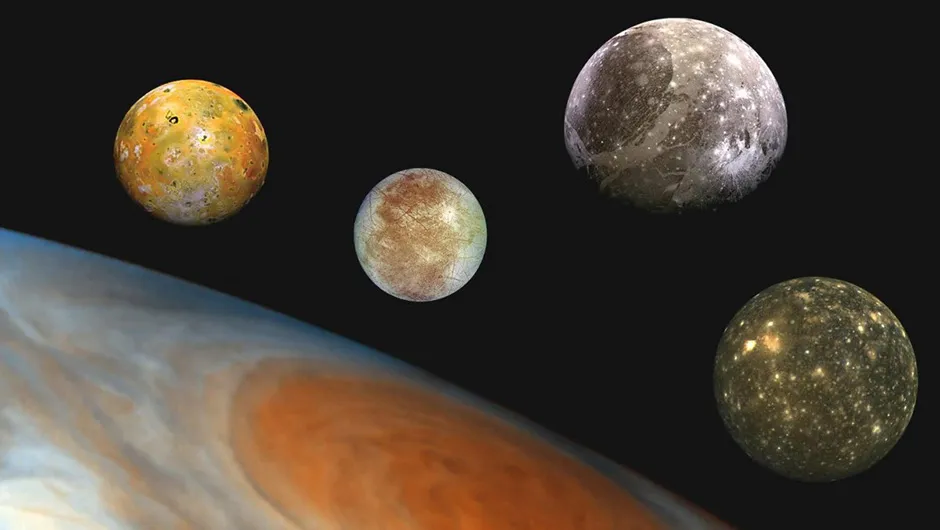

An illustration showing Jupiter and its four Galilean moons, from left to right Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto. Credit: NASA/JPL/DLR

An illustration showing Jupiter and its four Galilean moons, from left to right Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto. Credit: NASA/JPL/DLR

Why exomoons must exist

Sadly for me, Earth has only the one natural satellite, but we’ve come to learn that moons are everywhere in the Solar System, ever since Galileo spotted Jupiter’s four biggest ones – and got sentenced to house arrest for his trouble.

Even Pluto, the demoted dwarf planet, has one (Charon). Some asteroids have moons of sorts too.

So, given how common moons are, it’s a genuine source of annoyance that we haven’t yet discovered a single moon orbiting an exoplanet.

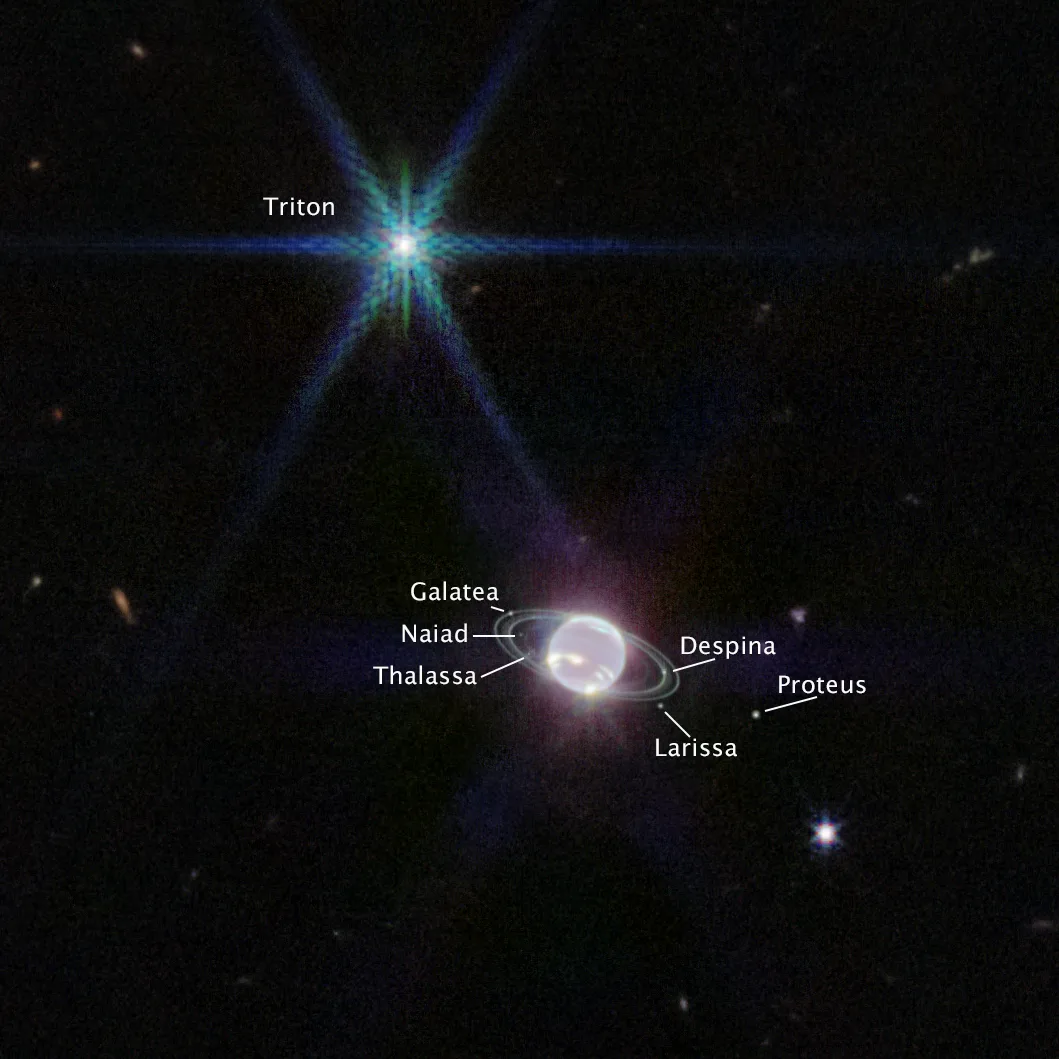

An annotated view of Neptune, its rings, moons and large moon Triton captured by the James Webb Space Telescope, 12 July 2022. Credit: Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, processed by Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

An annotated view of Neptune, its rings, moons and large moon Triton captured by the James Webb Space Telescope, 12 July 2022. Credit: Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, processed by Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

But we do have a name for them, at least: exomoons.

Our entire understanding of the Universe rests on the cosmological principle: the idea that the Universe is pretty much the same everywhere, in all directions, because the laws of physics are the same.

There are no special areas where special things happen.

Therefore, if all the completely average Solar System planets (and planet-adjacent bodies) that are orbiting our – let’s face it – pretty average star have moons, then loads of the exoplanets must also have moons.

So why haven’t we discovered any yet?

This artist’s illustration shows a moon in orbit around a gas giant exoplanet.NASA GSFC: Jay Friedlander and Britt Griswold

This artist’s illustration shows a moon in orbit around a gas giant exoplanet.NASA GSFC: Jay Friedlander and Britt Griswold

How we search for exomoons

Like many things in astronomy, the answer is: because it’s hard.

There are a few approaches we can use to search for exomoons and all involve detecting a signal in our data.

Because our data isn’t perfect, it has a bunch of noise as well as the signals we want to dig out.

The challenge is teasing out the signal from the noise – hence why astronomers go on and on about the ‘signal-to-noise ratio’.

The issue with moons is that, no matter how you look for them, the signal is tiny.

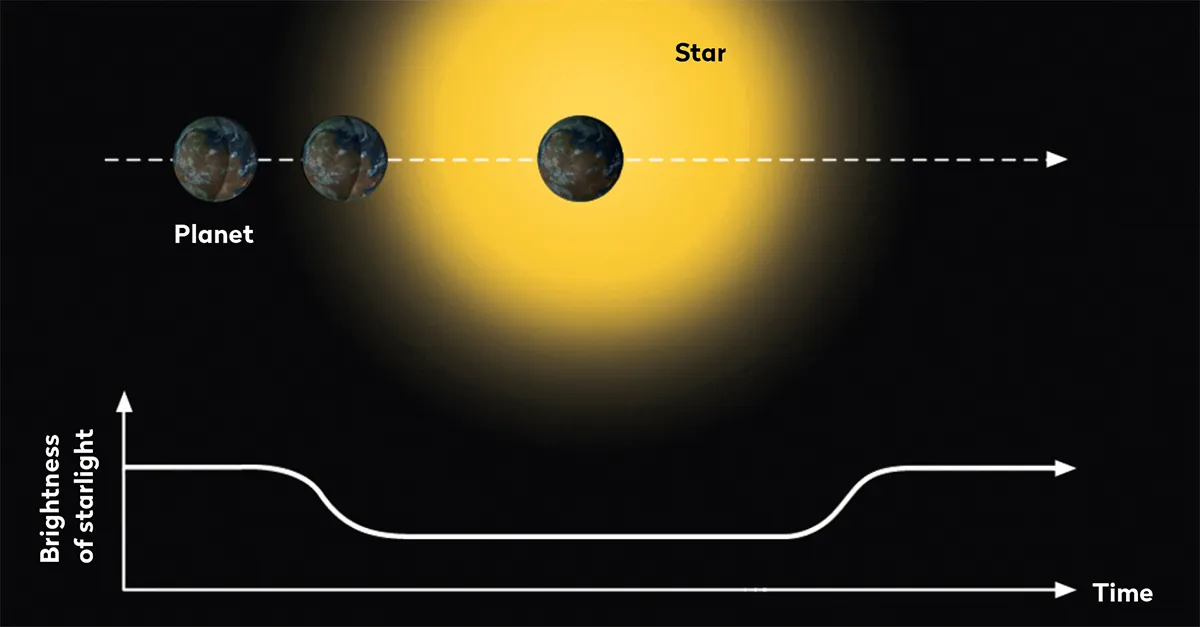

The transit method of detecting exoplanets sees astronomers measure dips in starlight as a planet passes in front of its host star.

The transit method of detecting exoplanets sees astronomers measure dips in starlight as a planet passes in front of its host star.

Most exomoon searches so far have used the transit method.

This is the most successful method for detecting new exoplanets and relies on spotting repeated dips in brightness as an alien planet passes in front of its star.

If the planet has a moon in tow, then additional, much smaller dips might also be visible.

A lot of work has gone into simulating these signals for dozens of existing exoplanet systems, but the issue is that you need a pretty big telescope to spot a signal this small.

JWST might be the only scope capable of realistically detecting an exomoon in transit right now, and it’s a little bit oversubscribed.

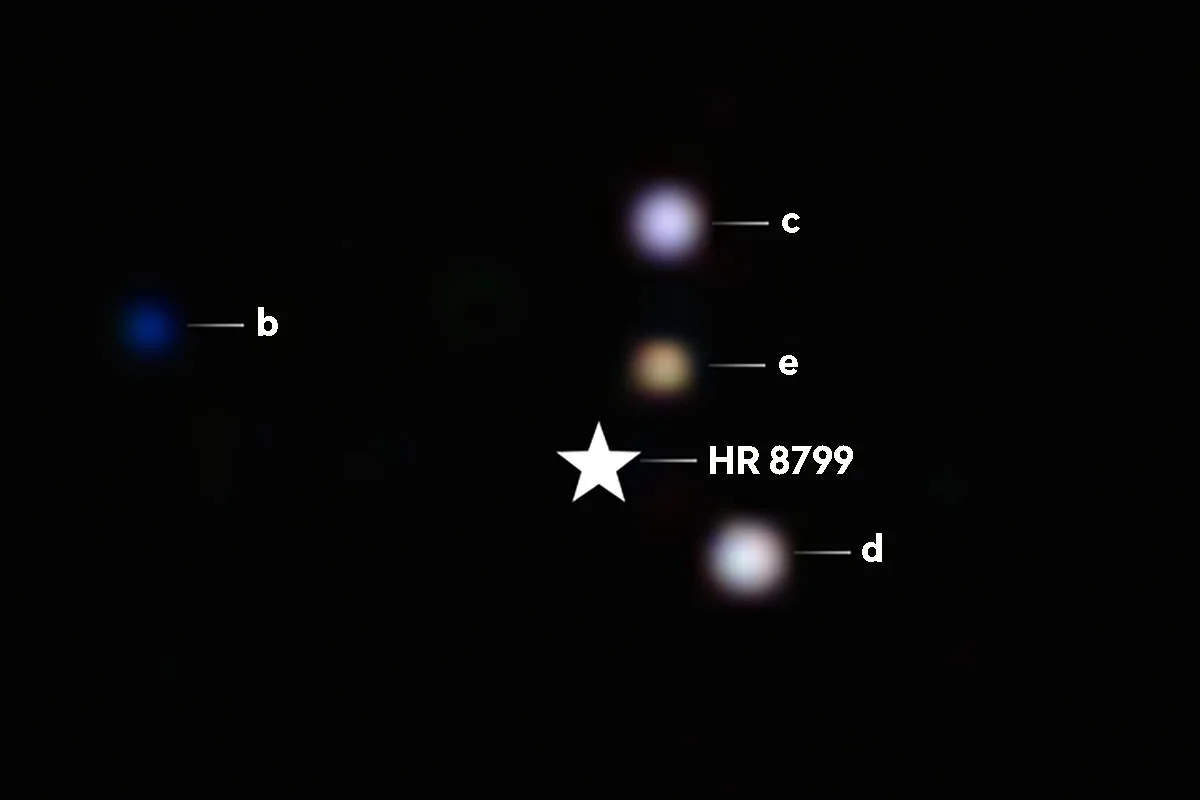

Direct image of exoplanets (the dots marked b, c, d and e) around star HR 8799, captured by the James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Laurent Pueyo (STScI), William Balmer (JHU), Marshall Perrin (STScI)

Direct image of exoplanets (the dots marked b, c, d and e) around star HR 8799, captured by the James Webb Space Telescope. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Laurent Pueyo (STScI), William Balmer (JHU), Marshall Perrin (STScI)

A new technique for exomoon hunting

However, new hope has entered the building in the form of astrometry!

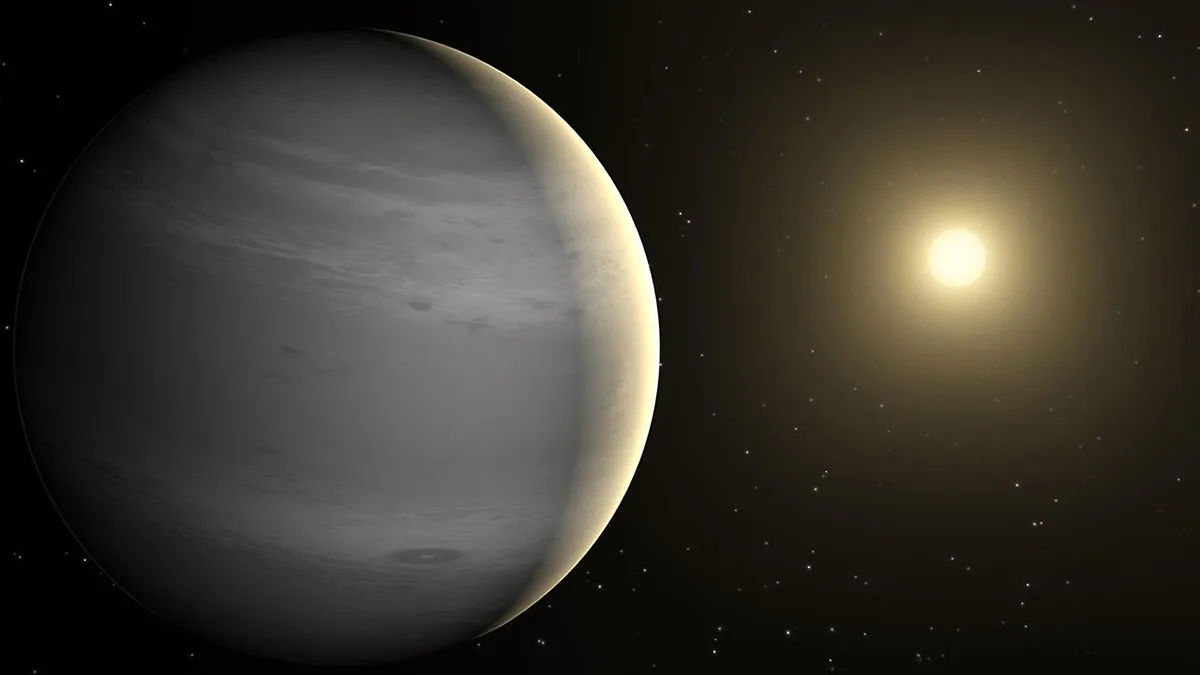

A team recently found tentative evidence of a satellite orbiting a directly imaged gas giant called HD 206893 B.

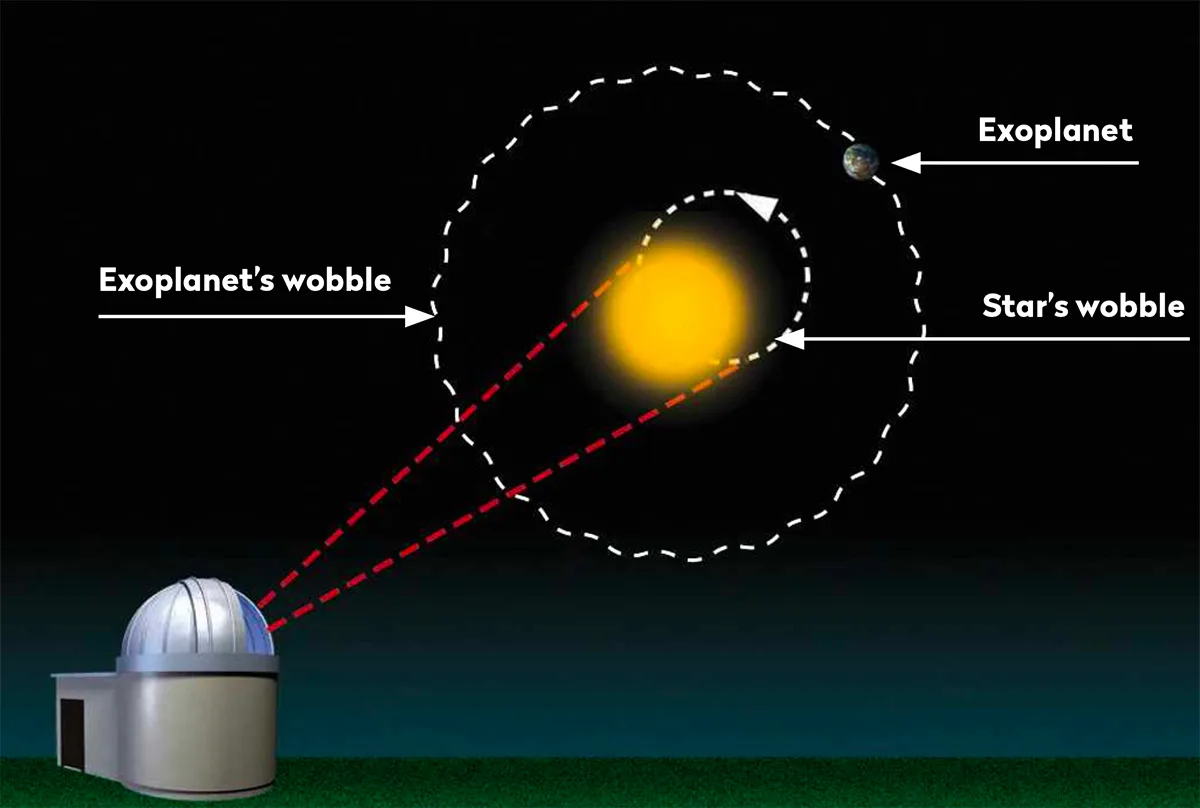

Astrometry tracks a planet’s motion over time, looking for subtle wobbles that hint at an orbiting moon. Credit: BBC Sky at Night Magazine

Astrometry tracks a planet’s motion over time, looking for subtle wobbles that hint at an orbiting moon. Credit: BBC Sky at Night Magazine

Because this object is directly imaged, the team could track its motion and search for deviations (or wobbles) as it orbits its star.

The signal they found is unconfirmed, but if it is caused by an exomoon, it’s a whopper – about 125 times more massive than Earth. That’s… chunky.

Either way, it’s a thrilling step in the right direction– and adding a whole new technique to the moon hunt is especially cool.

Artist’s impression of gas giant exoplanet HD 206893 b. Credit: NASA

Artist’s impression of gas giant exoplanet HD 206893 b. Credit: NASA

I have a feeling that we’re close to confirming the first exomoon.

So many folks are working on this right now and, with new techniques and new space telescopes launching soon, we’ll have a load more data to comb through.

Let’s just hope we’ve moved on from house arrest for whoever discovers them!

This article appeared in the February 2026 issue of BBC Sky at Night Magazine