As an astronomer, I collect stars. There are several hundred billion of them in our Galaxy, the Milky Way, so it’s important to find a way to categorise them.

While others might rank their stars by colour or size, I prefer to order them chronologically. That way, we can simply look through them to read the history of the Universe.

There is, however, a glaring gap in my collection: the very first generation of stars are missing. And I’m not the only one to have encountered this problem.

All the world’s astronomers – despite the multitude of telescopes at our disposal and centuries of diligent observation – have failed to find a single one. If we’re trying to read through the history of the Universe, then our library is missing the first volume.

And this is a problem. Stars are the way the Universe grows and evolves. They’re powered by fusion, where light elements, such as hydrogen, fuse together to form heavier elements.

When they die, they explode in a supernova, flinging all the heavy elements they created inside their core into the surrounding neighbourhood. This instantly enriches the pristine, primordial gas with the heavy elements required for new stars, planets and even life.

You see, these first stars are different from all those that came after. Their novelty comes from their unique chemistry.

Like all stars, they were born from clouds of gas that collapsed under their own gravity. As they were the first stars, they only contained the hydrogen, helium and a sprinkling of lithium that was created in the Big Bang.

This unique chemistry meant they had fewer ways to lose heat than younger stars do, and so the clouds stayed puffed up.

This allowed the clouds to grow much larger before they collapsed, meaning those early stars could be several hundred times more massive than our Sun.

Now, on its own, the fact that they’re massive isn’t an overly astonishing detail. Many stars in the Milky Way are tens of times the Sun’s mass, with a few reaching around 90 times as massive. But these modern giants are vanishingly rare.

Most stars that exist today are red dwarfs, smaller than our Sun. If our understanding of how these stars grew is correct, then the first stars were a community of stellar behemoths.

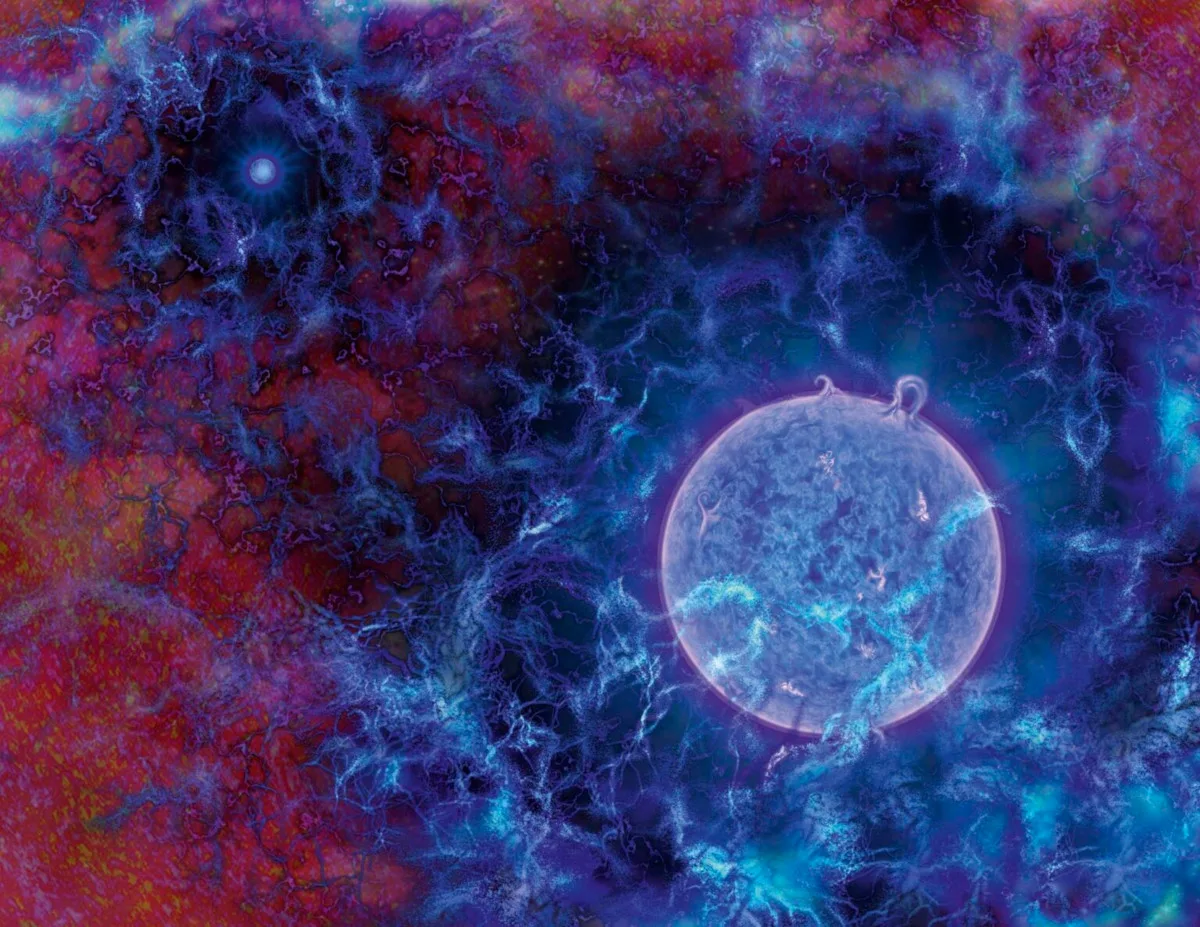

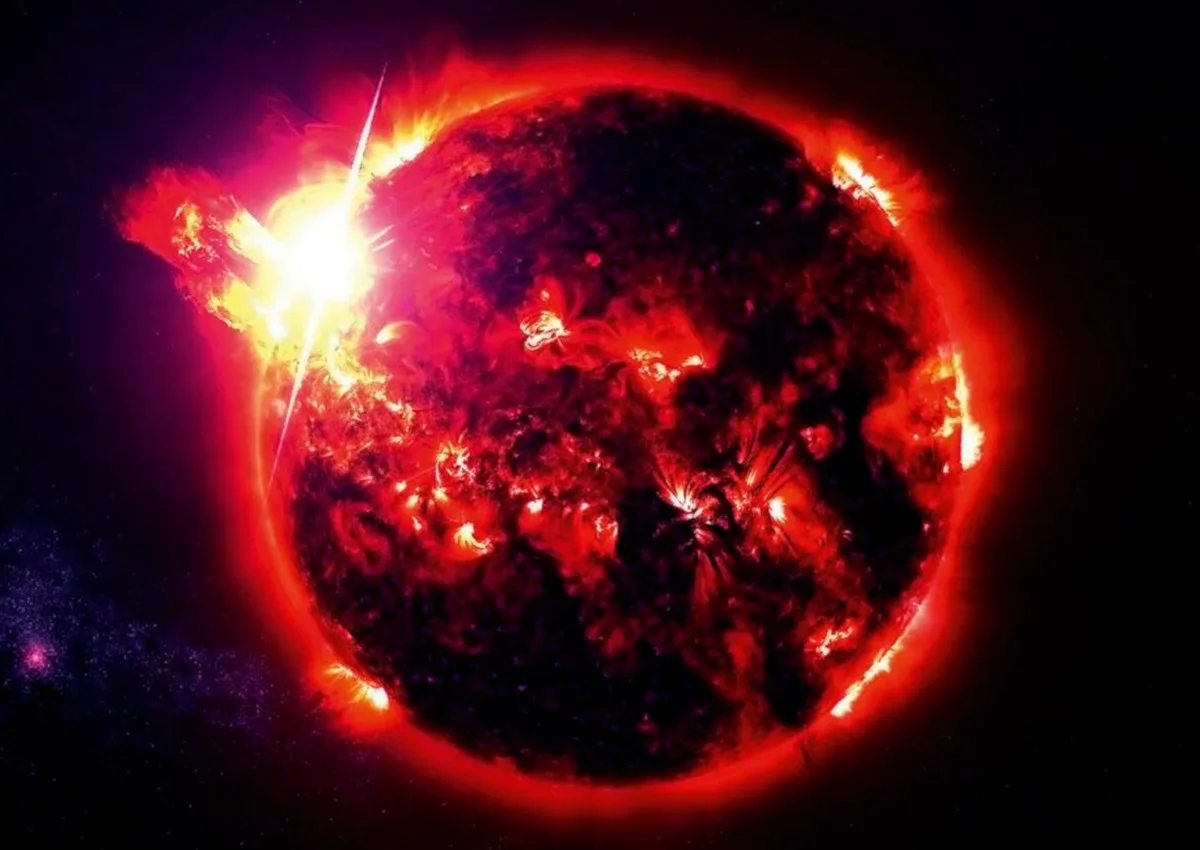

The Big Bang created light elements, such as hydrogen, helium and trace amounts of lithium, which then formed into the first stars – Image credit: Science Photo Library

The Big Bang created light elements, such as hydrogen, helium and trace amounts of lithium, which then formed into the first stars – Image credit: Science Photo Library

If such a star were in place of the Sun, our sky would be dominated by a blazing blue-white giant with a surface temperature of tens of thousands of degrees Celsius.

Its ultraviolet radiation would vaporise the oceans in an instant and its visible starlight would be so bright that our atmosphere would bend it right around the planet, creating a perpetual daytime.

This enormous size also explains why we struggle to find them today, as mass sets the speed of fusion in a star’s core. The rule is counterintuitive but simple: the more massive a star, the shorter its lifespan.

Stars are like cars. A hulking pick-up truck has a big tank, but guzzles its fuel; a small city car has a tiny tank, but sips its contents and so can go much further. Similarly, modest-sized stars are frugal consumers of fuel and so linger.

Meanwhile, gargantuan stars that are 100s of times the mass of the Sun blaze through theirs in a few million years before dying in a catastrophic supernova.

If all the first stars were such giants, then the reason we can’t find them is because they all blinked out of existence over 13 billion years ago.

The first stars were the ones to start it all, the pioneers that changed the Universe from a dark, empty expanse to a bright, thriving ecosystem.

But in doing so, they enriched that primordial gas with those first heavy elements, meaning pristine stars could no longer form – the first stars became irreproducible rare treasures.

The first stars mark a pivotal change in the history of the Universe. They’re definitely worth searching for, and yet they remain elusive.

Slimming down stars An illustration of how the first stars to form in the Universe might have looked – Image credit: Alamy

An illustration of how the first stars to form in the Universe might have looked – Image credit: Alamy

The fact that we haven’t seen these stars is a massive problem. Literally. Because while our theories and predictions suggest some of the early stars were stellar giants, we don’t know if they all were.

In fact, there’s a growing number of advanced observations, experiments and simulations that suggest the early Universe was filled with a diverse set of celestial wonders – some of which might have been small enough to still be around today.

Astronomy isn’t, generally, an experimental science. We can’t recreate a star or dissect one to understand its inner workings. Instead, we’re restricted to observing what the Universe has to show us.

But in 2025, researchers at the Max-Planck-Institut für Kernphysik in Heidelberg, Germany, conducted a rare piece of astronomical experimentation. Using a particle accelerator, they were able to create the conditions found in the centre of a collapsing cloud of primordial gas.

They looked at the first ever molecules created in the Universe – a helium atom linked to a hydrogen nucleus – and discovered they were potentially far more important in early star formation than previously thought.

The presence of these molecules allowed the gas clouds to dissipate heat much faster, causing them to collapse sooner, possibly nudging the mass of the first stars down slightly. And remember, the less massive a star is, the longer it’ll live.

In simulations, too, the first stars have begun slimming down. For years, computing limits meant we could only model the very centre of a collapsing gas cloud in detail, but struggled to simulate the surrounding disc of gas in detail.

In the stars of today’s Universe, heavy elements help those discs cool and clump, fragmenting into clusters of smaller stars. As early stars only contained hydrogen and helium, we assumed the discs of gas stayed smooth, feeding one enormous central star.

Now, astronomers have the computer power to simulate the full disc, and the results have been shocking.

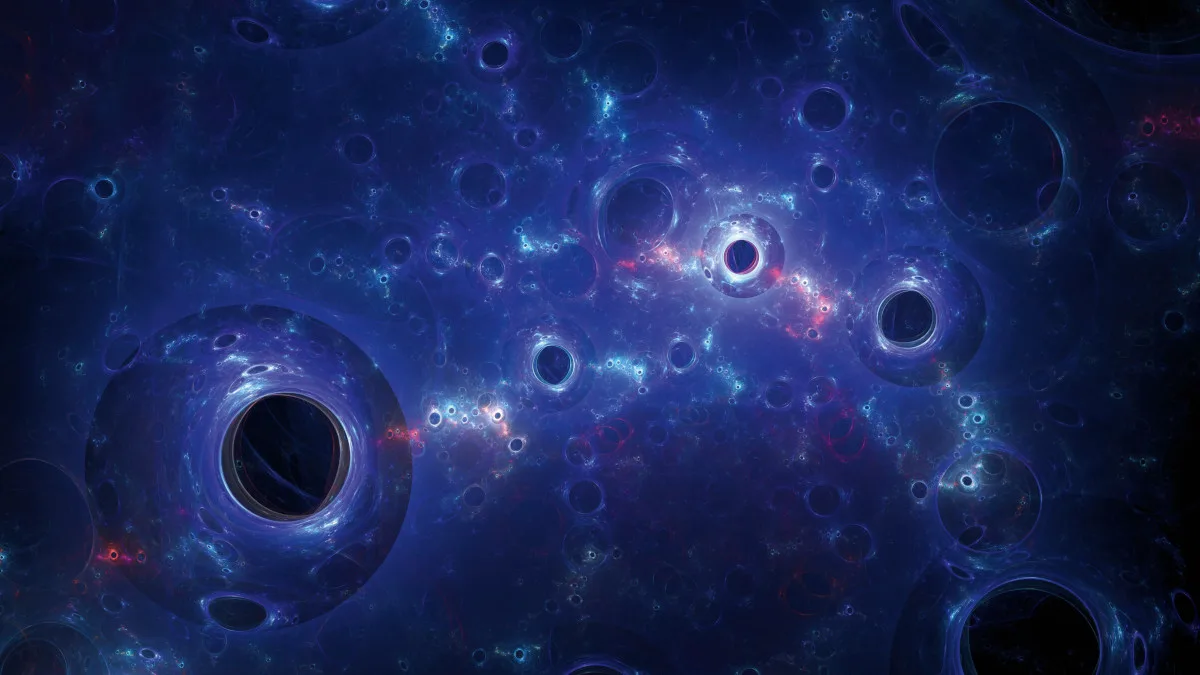

Black holes, illustrated here, could be responsible for the accelerated growth rate of the first stars – Image credit: Science Photo Library

Black holes, illustrated here, could be responsible for the accelerated growth rate of the first stars – Image credit: Science Photo Library

The gas wasn’t calm at all. Turbulent motions, often supersonic, whipped through it, carving out pockets that could cool and collapse into much smaller stars.

It seems at least some of the first stars were only a few times the mass of the Sun. Stars that size live for billions of years, not millions, meaning there could still be some around today.

Even black holes might have had a role in determining the masses of the first stars.

Primordial black holes are theoretical entities that could have formed shortly after the Big Bang.

They can be anywhere between the mass of an asteroid up to 100,000 times the mass of the Sun, but even the tiniest of primordial black holes has enough gravitational heft to draw together gas and dark matter, accelerating the formation of the first stars.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the scale, massive black holes can actually disrupt fragmenting gas clouds, stopping them from collapsing and forming into stars.

Since we’ve never seen a primordial black hole, it’s difficult to pin down how much each of these mechanisms might have affected the formation of the first stars.

But these simulations are important because they show just how much exotic physics goes into determining when and how those first stars formed and, conversely, how much we can learn about physics when we finally do determine what the first stars looked like.

The key takeaway from these simulations is that there could have been a set of first stars that were much less massive than previously assumed, small enough to have survived until the present day.

But finding them isn’t easy.

Read more:

Hunting down the first stars

One of the main ways we identify certain types of stars is through spectroscopy. This method splits the light from a star into a rainbow, or spectrum, revealing patterns that show the presence of certain chemicals.

For example, if carbon is present, it’ll cause very specific colours, or wavelengths, to be missing from that rainbow, creating a sort of barcode effect of dark lines.

Each element has its own ‘barcode’, or spectroscopic signature, allowing us to work out what lies within each of those points of light in the night sky.

Thanks to its simple elemental structure, a first star’s key signature is light that shows only signs of hydrogen and helium.

Stellar archaeologists have come vanishingly close to finding one, identifying stars that have as few as five elements. This is still too many to be a true first star, but, excitingly, these seem to be their direct descendants.

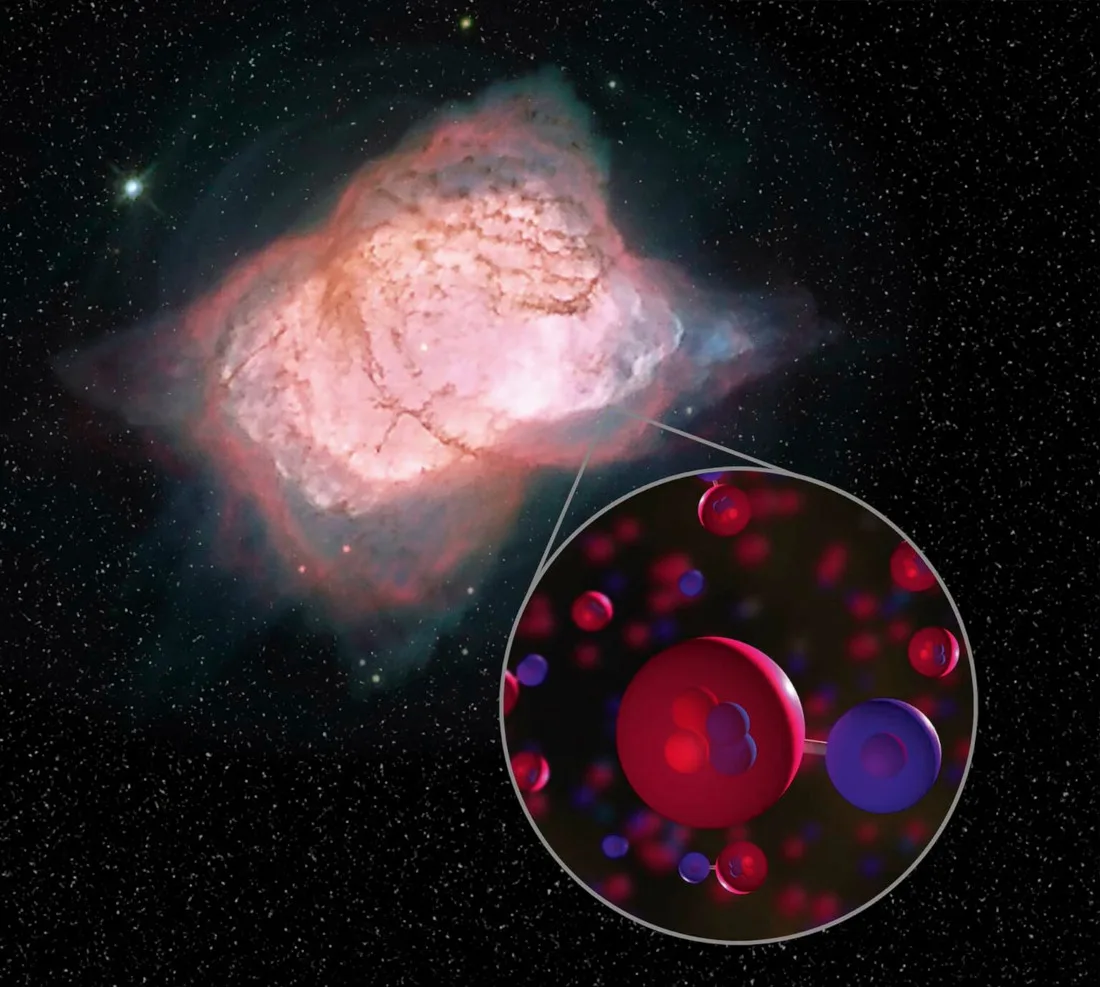

A diagram of a helium hydride molecule, the first type of molecule to form in the early Universe – Image credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble/Judy Schmidt

A diagram of a helium hydride molecule, the first type of molecule to form in the early Universe – Image credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble/Judy Schmidt

From looking at the elements they contain, we can work out that these stars formed from the detritus thrown out by the supernova of a single first star.

We can even work out the mass of that star.

At the moment, we have only a handful of these descendants, but we’re beginning to build up an idea of what the ancestral first stars looked like just from the heavy element inheritance embedded in their long-lived descendants.

The difficulty with this kind of stellar archaeology is that a star that’s been hanging around the cosmic neighbourhood for over 13 billion years is going to have gathered some dirt on its surface, making it much harder for astronomers to spot.

Stellar archaeologists have to look at each individual star and figuratively dust off this grime from what they think is the true light underneath.

It’s a slow, painstaking process, just like real archaeology. It could be that the first stars have been there all along – we just needed to blow the dust off to reveal them.

Resurrecting our stellar ancestors

The stellar archaeologists may be hard at work, picking apart starlight to find potential low-mass first stars, but we shouldn’t write off those high-mass ones just yet.

Yes, they all died over 13 billion years ago, but astronomers aren’t deterred by such matters. Not when we have telescopes – our very own time machines.

Light takes time to travel, so the farther we look, the further back in time we see.

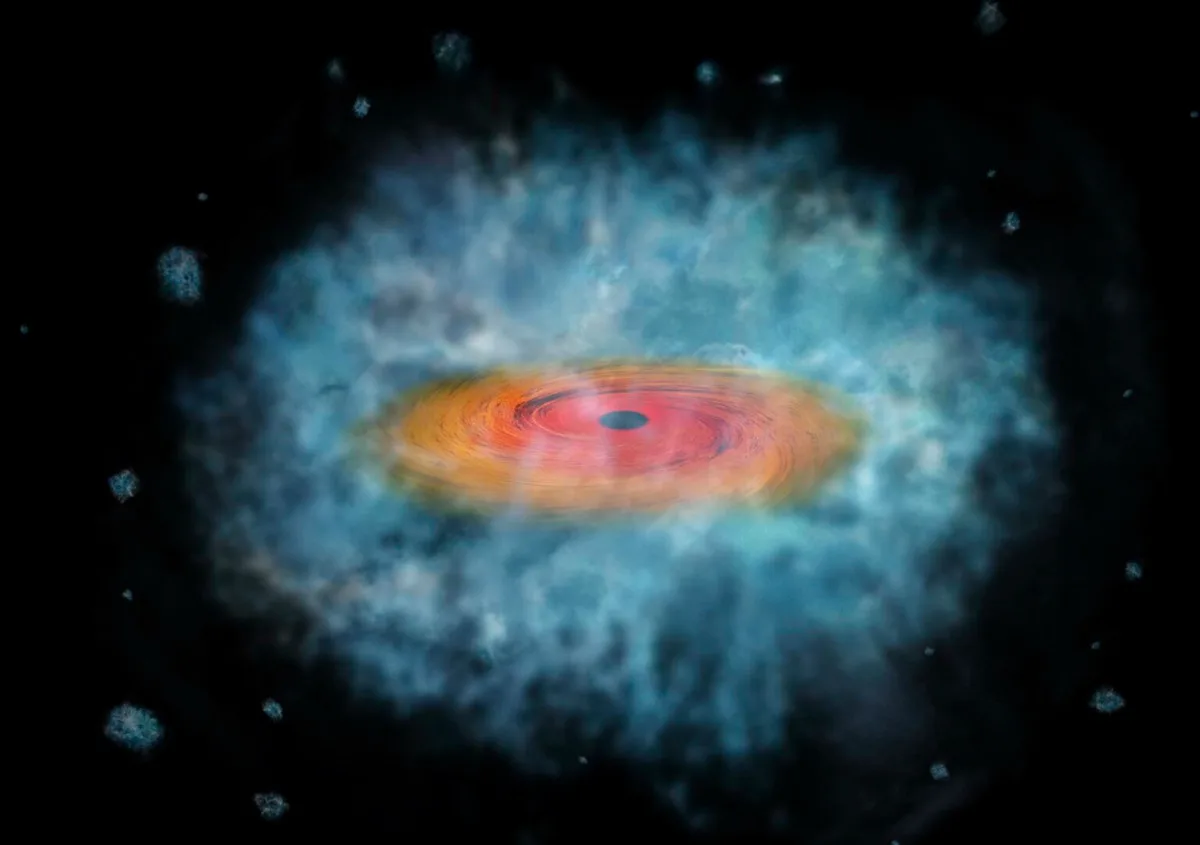

Direct collapse black holes, illustrated here, may explain the existence of supermassive black holes that appear too big for their age – Image credit: NASA/CXC/M Weiss

Direct collapse black holes, illustrated here, may explain the existence of supermassive black holes that appear too big for their age – Image credit: NASA/CXC/M Weiss

To glimpse the first stars, we just need to catch light that’s been on the road for over 13.5 billion years. But the farther the light has travelled, the fainter it’ll be.

The light from a star so far away that it’s been travelling for 13.5 billion years would be 40,000 times fainter than the limit of the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) – the most powerful telescope astronomers currently have.

But all is not lost. What the JWST can see, is galaxies from the era of the first stars. And now that we’re looking at them, we’ve found something astonishing.

Although the JWST is looking at a time when the Universe should have had very few stars at all, bizarrely, it’s finding entire galaxies full of them, much earlier than anyone thought possible.

Even more perplexing is that many of these newborn galaxies already host supermassive black holes at their centres that are far too big for their age – they shouldn’t have had time to grow to such an enormous size.

What was going on in the early Universe to kick-start this incredible growth spurt?

Dark stars

One idea is that the giants of the first generation of stars were able to trigger something called direct collapse black holes.

Massive stars emit a fierce amount of ultraviolet light, which would heat nearby gas clouds, allowing them to grow to thousands of times the mass of the Sun.

When gravity finally wins, not even the fusion that normally stops stars from completely collapsing can stop the fall. The entire cloud collapses directly into a black hole, potentially giving the overly large supermassive black holes their early start.

Another possibility looks to the unseen scaffolding of the cosmos: dark matter. This mysterious substance makes up most of the Universe’s mass, but we can’t see it directly.

We only know it’s there from seeing how its mass pulls on galaxies.

Hypothesised dark stars could also explain why so many supermassive black holes have been found in the early Universe – Image credit: Alamy

Hypothesised dark stars could also explain why so many supermassive black holes have been found in the early Universe – Image credit: Alamy

If whatever particles that make up dark matter can occasionally collide and annihilate, releasing energy, they might have powered an entirely different kind of object: a dark star.

Instead of fusion at the core, dark stars are hypothetically powered by dark matter annihilation. Freed from a star’s usual limits, dark stars could balloon to the size of Saturn’s orbit while still shining brilliantly.

When their dark matter fuel finally runs out, they too would collapse, forming black holes hundreds of thousands of times the mass of the Sun.

Whether these dark stars ever existed is still uncertain, but they might finally explain the oversized black holes JWST keeps uncovering.

Perhaps, while we’ve been chasing the first stars, their spectacular afterlives have been staring at us all along. Even if the first stars are missing from my collection, perhaps the first black holes aren’t.

It’s these kinds of objects that have made the long search for the first stars worth it – we should be careful not to ignore all the treasure we might have kicked out of the way in our rush to hunt them down.

The fingerprints of the first stars are everywhere: in the chemistry of ancient stars, in the seeds of black holes and in the strange new stellar categories they’ve forced us to invent.

If this is the price of the search, then long may it continue.

Read more: