An interstellar comet first spotted passing through our solar system in July is beginning its departure from our corner of the universe — but first it will fly by Earth, and scientists are capturing stunning new images during its approach.Related video above: Why asteroid 2024 YR4 is unlikely to hit Earth in 2032Known as 3I/ATLAS, the comet will make its closest pass by us on Friday, coming within about 167 million miles (270 million kilometers) of our planet, but on the other side of the sun. For reference, the sun’s distance from Earth is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).Comet 3I/ATLAS won’t be visible to the naked eye and the optimal viewing window, which opened in November, has passed. Those hoping to glimpse it will need an 8-inch (20-centimeter) telescope or larger, according to EarthSky.The Virtual Telescope Project will share a livestream of the comet at 4:00 a.m. UTC on Saturday, or 11 p.m. ET Friday, after cloudy weather prevented a Thursday night streaming opportunity, said Gianluca Masi, astronomer and astrophysicist at the Bellatrix Astronomical Observatory in Italy and founder and scientific director of the Virtual Telescope Project.The comet is expected to remain visible to telescopes and space missions for a few more months before exiting our solar system, according to NASA.Astronomers have closely tracked the comet since its initial discovery over the summer in the hopes of uncovering details about its origin outside of our solar system as well as its composition. Multiple missions have observed the object in optical, infrared and radio wavelengths of light — and recently, scientists captured their first glimpses in X-rays to and discovered new details. The ingredients of an interstellar cometComets are like dirty snowballs left over from the formation of solar systems.A comet’s nucleus is its solid core, made of ice, dust and rocks. When comets travel near stars such as the sun, heat causes them to release gas and dust, which creates their signature tails.Astronomers are interested in capturing as many observations of the comet as they can because as it nears the sun, material releasing from the object could reveal more about its composition — and the star system where it originated.“When it gets closest to the sun, you get the most holistic view of the nucleus possible,” Seligman said. “One of the main things driving most cometary scientists is, what is the composition of the volatiles? It shows you the initial primordial material that it formed from.”Scientists have used powerful tools, such as the Hubble Space and James Webb Space telescopes, along with a multitude of space-based missions, such as SPHEREx, to study the comet.The SPHEREx and Webb observations detected carbon dioxide, water, carbon monoxide, carbonyl sulphide and water ice releasing from the comet as it neared the sun, according to the ESA.Preliminary estimates indicate that the interstellar comet is 3 billion to 11 billion years old, according to a study coauthored by Seligman and Aster Taylor, a doctoral student and Fannie and John Hertz Foundation Fellow at the University of Michigan, in August. For reference, our solar system is estimated to be about 4.6 billion years old.Carbon dioxide turns directly from a solid into a gas in response to temperature changes much more easily than most elements — which means the comet has likely never been close to another star before its brush with the sun, Seligman said.All eyes on 3I/ATLASThe interstellar comet faded from the view of ground-based telescopes in October, but it remained in sight for missions such as PUNCH, or Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere, and SOHO, or the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory. The object also made its closest approach of Mars on October 3, coming within 18.6 million miles (30 million kilometers) of the red planet — and the spacecraft orbiting it.While the government shutdown has prevented data sharing from any NASA missions that have observed the comet since October 1, the ESA’s Mars Express and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter attempted to capture views of 3I/ATLAS in October.The cameras aboard those missions are designed to study the relatively close, bright surface of Mars, but ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter managed to observe the comet as a fuzzy white dot.“This was a very challenging observation for the instrument,” Nick Thomas, principal investigator of the orbiter’s camera, said in a statement, noting the comet is around 10,000 to 100,000 times “fainter than our usual target.”ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or Juice, will also attempt to observe 3I/ATLAS in November using multiple instruments despite the comet being farther from the spacecraft than it was when observed by the Mars orbiters. But astronomers don’t expect to receive the observations until February due to the rate at which the spacecraft is sending data back to Earth.“We’ve got several more months to observe it,” Seligman said. “And there’s going to be amazing science that comes out.”X-raying an interstellar visitorComets that originate in our solar system emit X-rays, but astronomers have long wondered whether interstellar comets behave the same.Although previous attempts to find out were made as two other interstellar comets passed through our solar system in 2017 and 2019, no X-rays were detected.But that all changed with 3I/ATLAS.Japan’s X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission, or XRISM, observed 3I/ATLAS for 17 hours in late November with its Xtend telescope. The instrument captured X-rays fanning out to a distance of 248,000 miles (400,000 kilometers) from the comet’s solid core, or nucleus, which could be a result of clouds of gas around the object, according to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. But more observations are needed to confirm the finding.X-rays can originate from interactions between gases given off by the comet — such as water vapor, carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide — and the continuous stream of charged particles releasing from the sun called solar wind. Comets, which are a combination of ice, rock, dust and gas, heat up as they approach stars like the sun, causing them to sublimate materials. XRISM detected signatures of carbon, oxygen and nitrogen near the comet’s nucleus. The European Space Agency’s X-ray space observatory XMM-Newton also observed the interstellar comet on December 3 for about 20 hours using its most sensitive camera. A dramatic image released by the agency shows the red X-ray glow of the comet.The X-ray observations, combined with others across various wavelengths of light, could reveal what the comet is made of — and just how similar or different the object is from those in our own solar system.

An interstellar comet first spotted passing through our solar system in July is beginning its departure from our corner of the universe — but first it will fly by Earth, and scientists are capturing stunning new images during its approach.

Related video above: Why asteroid 2024 YR4 is unlikely to hit Earth in 2032

Known as 3I/ATLAS, the comet will make its closest pass by us on Friday, coming within about 167 million miles (270 million kilometers) of our planet, but on the other side of the sun. For reference, the sun’s distance from Earth is about 93 million miles (150 million kilometers).

Comet 3I/ATLAS won’t be visible to the naked eye and the optimal viewing window, which opened in November, has passed. Those hoping to glimpse it will need an 8-inch (20-centimeter) telescope or larger, according to EarthSky.

The Virtual Telescope Project will share a livestream of the comet at 4:00 a.m. UTC on Saturday, or 11 p.m. ET Friday, after cloudy weather prevented a Thursday night streaming opportunity, said Gianluca Masi, astronomer and astrophysicist at the Bellatrix Astronomical Observatory in Italy and founder and scientific director of the Virtual Telescope Project.

The comet is expected to remain visible to telescopes and space missions for a few more months before exiting our solar system, according to NASA.

NASA/ESA/David Jewitt (UCLA) via CNN Newsource

Hubble captured this image of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS on July 21.

NASA, ESA, STScI, D. Jewitt (UCLA), M.-T. Hui (Shanghai Astronomical Observatory), J. DePasquale (STScI) via AP

This image, provided by NASA, shows the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS captured by the Hubble Space Telescope on Nov. 30, 2025, about 178 million miles from Earth.

Astronomers have closely tracked the comet since its initial discovery over the summer in the hopes of uncovering details about its origin outside of our solar system as well as its composition. Multiple missions have observed the object in optical, infrared and radio wavelengths of light — and recently, scientists captured their first glimpses in X-rays to and discovered new details.

The ingredients of an interstellar comet

Comets are like dirty snowballs left over from the formation of solar systems.

A comet’s nucleus is its solid core, made of ice, dust and rocks. When comets travel near stars such as the sun, heat causes them to release gas and dust, which creates their signature tails.

Astronomers are interested in capturing as many observations of the comet as they can because as it nears the sun, material releasing from the object could reveal more about its composition — and the star system where it originated.

“When it gets closest to the sun, you get the most holistic view of the nucleus possible,” Seligman said. “One of the main things driving most cometary scientists is, what is the composition of the volatiles? It shows you the initial primordial material that it formed from.”

Scientists have used powerful tools, such as the Hubble Space and James Webb Space telescopes, along with a multitude of space-based missions, such as SPHEREx, to study the comet.

Gianluca Masi

This photo provided by Gianluca Masi shows the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it streaks through space, 190 million miles from Earth, on Wednesday, Nov. 19, 2025, seen from Manciano, Italy.

The SPHEREx and Webb observations detected carbon dioxide, water, carbon monoxide, carbonyl sulphide and water ice releasing from the comet as it neared the sun, according to the ESA.

Preliminary estimates indicate that the interstellar comet is 3 billion to 11 billion years old, according to a study coauthored by Seligman and Aster Taylor, a doctoral student and Fannie and John Hertz Foundation Fellow at the University of Michigan, in August. For reference, our solar system is estimated to be about 4.6 billion years old.

Carbon dioxide turns directly from a solid into a gas in response to temperature changes much more easily than most elements — which means the comet has likely never been close to another star before its brush with the sun, Seligman said.

All eyes on 3I/ATLAS

The interstellar comet faded from the view of ground-based telescopes in October, but it remained in sight for missions such as PUNCH, or Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere, and SOHO, or the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory. The object also made its closest approach of Mars on October 3, coming within 18.6 million miles (30 million kilometers) of the red planet — and the spacecraft orbiting it.

While the government shutdown has prevented data sharing from any NASA missions that have observed the comet since October 1, the ESA’s Mars Express and ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter attempted to capture views of 3I/ATLAS in October.

The cameras aboard those missions are designed to study the relatively close, bright surface of Mars, but ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter managed to observe the comet as a fuzzy white dot.

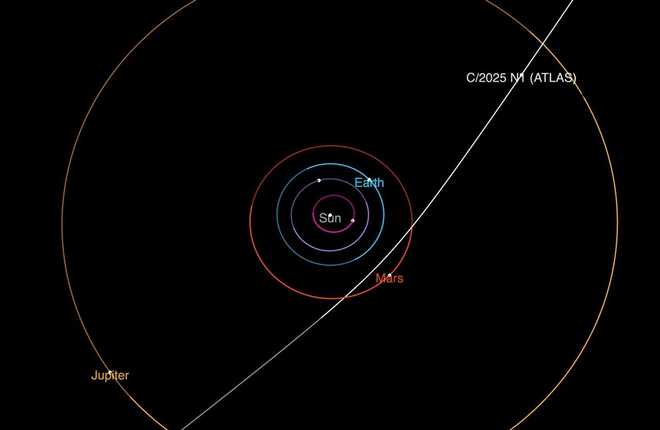

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This diagram shows the trajectory of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS as it passes through the solar system. It made its closest approach to the Sun in October.

“This was a very challenging observation for the instrument,” Nick Thomas, principal investigator of the orbiter’s camera, said in a statement, noting the comet is around 10,000 to 100,000 times “fainter than our usual target.”

ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, or Juice, will also attempt to observe 3I/ATLAS in November using multiple instruments despite the comet being farther from the spacecraft than it was when observed by the Mars orbiters. But astronomers don’t expect to receive the observations until February due to the rate at which the spacecraft is sending data back to Earth.

“We’ve got several more months to observe it,” Seligman said. “And there’s going to be amazing science that comes out.”

X-raying an interstellar visitor

Comets that originate in our solar system emit X-rays, but astronomers have long wondered whether interstellar comets behave the same.

Although previous attempts to find out were made as two other interstellar comets passed through our solar system in 2017 and 2019, no X-rays were detected.

But that all changed with 3I/ATLAS.

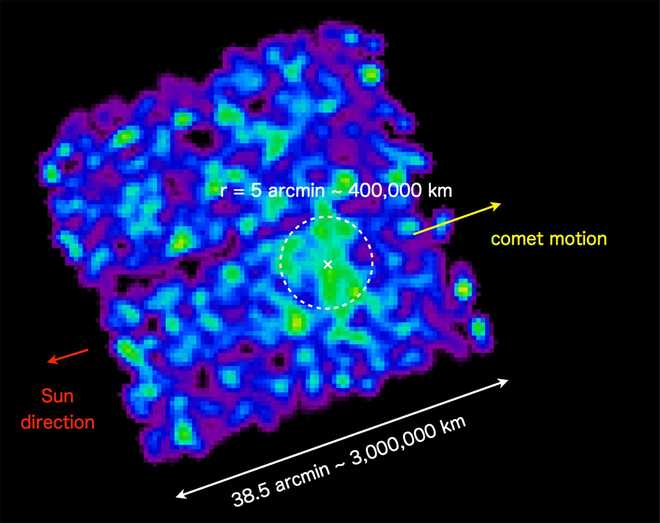

Japan’s X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission, or XRISM, observed 3I/ATLAS for 17 hours in late November with its Xtend telescope. The instrument captured X-rays fanning out to a distance of 248,000 miles (400,000 kilometers) from the comet’s solid core, or nucleus, which could be a result of clouds of gas around the object, according to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. But more observations are needed to confirm the finding.

JAXA/ESA via CNN Newsource

XRISM captured an image of comet 3I/ATLAS in X-ray light.

X-rays can originate from interactions between gases given off by the comet — such as water vapor, carbon monoxide or carbon dioxide — and the continuous stream of charged particles releasing from the sun called solar wind. Comets, which are a combination of ice, rock, dust and gas, heat up as they approach stars like the sun, causing them to sublimate materials. XRISM detected signatures of carbon, oxygen and nitrogen near the comet’s nucleus.

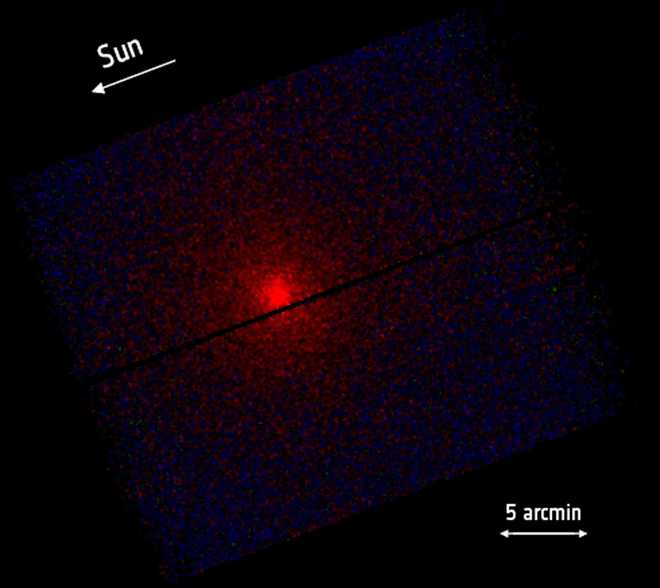

ESA/XMM-Newton/C. Lisse; S. Cabot & the XMM ISO Team via CNN Newsource

The XMM-Newton observatory spotted a red X-ray glow around the interstellar comet on Dec. 3.

The European Space Agency’s X-ray space observatory XMM-Newton also observed the interstellar comet on December 3 for about 20 hours using its most sensitive camera. A dramatic image released by the agency shows the red X-ray glow of the comet.

The X-ray observations, combined with others across various wavelengths of light, could reveal what the comet is made of — and just how similar or different the object is from those in our own solar system.