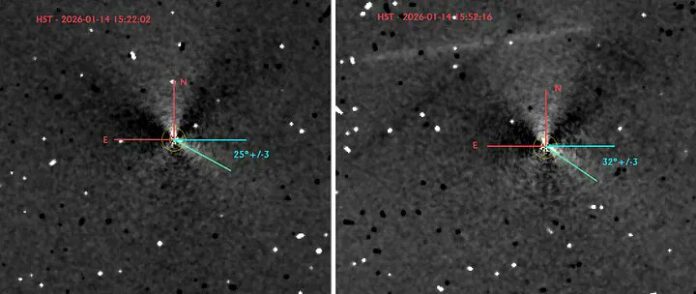

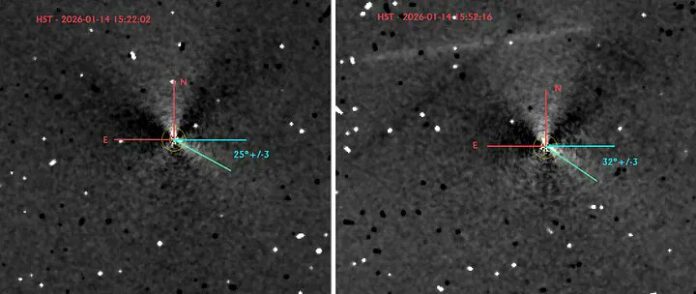

Side-by-side Hubble Space Telescope images of interstellar object 3I/ATLAS taken on January 14, 2026, showing measurable changes in jet orientation and outgassing geometry over a short time span. Directional vectors and angular offsets highlight evolving emission activity as the object responds to solar heating near perihelion. (Image credit: NASA/Hubble Space Telescope; analysis overlay for illustrative and editorial purposes under fair use, 17 U.S.C. §107.)

Side-by-side Hubble Space Telescope images of interstellar object 3I/ATLAS taken on January 14, 2026, showing measurable changes in jet orientation and outgassing geometry over a short time span. Directional vectors and angular offsets highlight evolving emission activity as the object responds to solar heating near perihelion. (Image credit: NASA/Hubble Space Telescope; analysis overlay for illustrative and editorial purposes under fair use, 17 U.S.C. §107.)

INSIDE THIS REPORT

For months, scientists have tracked 3I/ATLAS as an unusual interstellar visitor whose behavior refused to conform neatly to established comet models.

Now, new spectroscopic data has complicated the picture further, revealing chemical signatures that emerged only after the object’s closest approach to the Sun.

The findings raise a question that scientists are careful not to sensationalize, but can no longer avoid asking: could chemistry alone explain what we are seeing, or is something more complex at work?

New methane data forces scientists to confront whether biology, not geology alone, could explain delayed gas production

[USA HERALD] – As interstellar object 3I/ATLAS continues its outbound journey through the solar system, newly released data from NASA’s SPHEREx observatory and the James Webb Space Telescope is reshaping scientific understanding of its internal composition and behavior.

According to data released by mission scientists, SPHEREx detected multiple organic molecules associated with 3I/ATLAS, including methanol (CH₃OH), formaldehyde (H₂CO), methane (CH₄), and ethane (C₂H₆). The production rate of these organics was measured at approximately 14 percent relative to water molecules—an unusually high ratio for an object initially described as comet-like.

Among these findings, the most consequential is the robust spectroscopic detection of methane. Methane is considered a hyper-volatile compound, meaning it sublimates at much lower temperatures than substances such as carbon dioxide or water ice. Under conventional cometary models, methane present near the surface of an object would be expected to vaporize early, particularly during the first signs of solar heating.

Yet that did not occur.

Publicly available spectroscopy from both Webb and SPHEREx shows no detectable methane during the early outgassing phase observed in August 2025, well before perihelion. Methane appeared only later—after 3I/ATLAS passed closer to the Sun—suggesting the gas was not present in the object’s outermost layers.

This delayed emergence implies that methane-bearing material was buried beneath an outer shell depleted of hyper-volatiles, becoming exposed only after deeper solar heating fractured or eroded insulating layers. That conclusion alone challenges assumptions about how interstellar objects preserve internal stratification across cosmic timescales.

However, methane’s presence also raises a more controversial question.

On Earth, methane is produced both geologically and biologically. While abiotic methane is common in planetary environments, delayed methane release combined with complex organic chemistry has historically triggered scrutiny in planetary science, most notably in studies of Mars and icy moons.

Could methane detected on 3I/ATLAS be produced—or altered—by life processes?

At present, no direct evidence supports the existence of lifeforms aboard the object. Scientists emphasize that chemistry alone can plausibly account for the observations. Radiolysis, catalytic reactions within porous ice, or thermal cracking of complex hydrocarbons could all generate methane under the right conditions.

Still, the timing remains unusual.

Methane ice should not survive long near the surface of an object exposed to interstellar radiation and repeated stellar encounters. Its apparent absence early and sudden appearance later suggests either extraordinary preservation mechanisms or a source activated only after significant thermal stress.

According to mission scientists, further observations are planned as 3I/ATLAS approaches its gravitational interaction with Jupiter in March 2026. That encounter could expose additional internal layers or alter outgassing patterns in ways that help distinguish between competing explanations.

ANALYSIS

What makes 3I/ATLAS significant is not a single molecule, but the convergence of multiple anomalies. Interstellar origin, delayed volatile release, organic-rich chemistry, and structural resilience all point to an object that does not behave like solar-system-native comets.

In planetary science, methane occupies a unique evidentiary position. It is not proof of life, but it is a known byproduct of biological systems. When methane appears unexpectedly—especially in environments where it should have escaped long ago—it demands closer examination.

That does not mean jumping to conclusions. It means refining questions.

If humanity is capable of imagining a future where life is intentionally spread beyond Earth, it follows logically that other civilizations, older and more technologically advanced, might have explored similar strategies. That idea remains speculative, but it underscores why interstellar objects deserve heightened scrutiny rather than premature classification.

3I/ATLAS may ultimately prove to be entirely abiotic. Even so, the process of ruling out biology forces scientists to confront how incomplete current models are when applied to objects formed around other stars.

For now, 3I/ATLAS stands as a reminder that interstellar visitors carry histories far older and more complex than our solar system. Whether its methane originates from chemistry, physics, or processes not yet fully understood, the object is already reshaping how scientists think about what can survive—and travel—between stars.