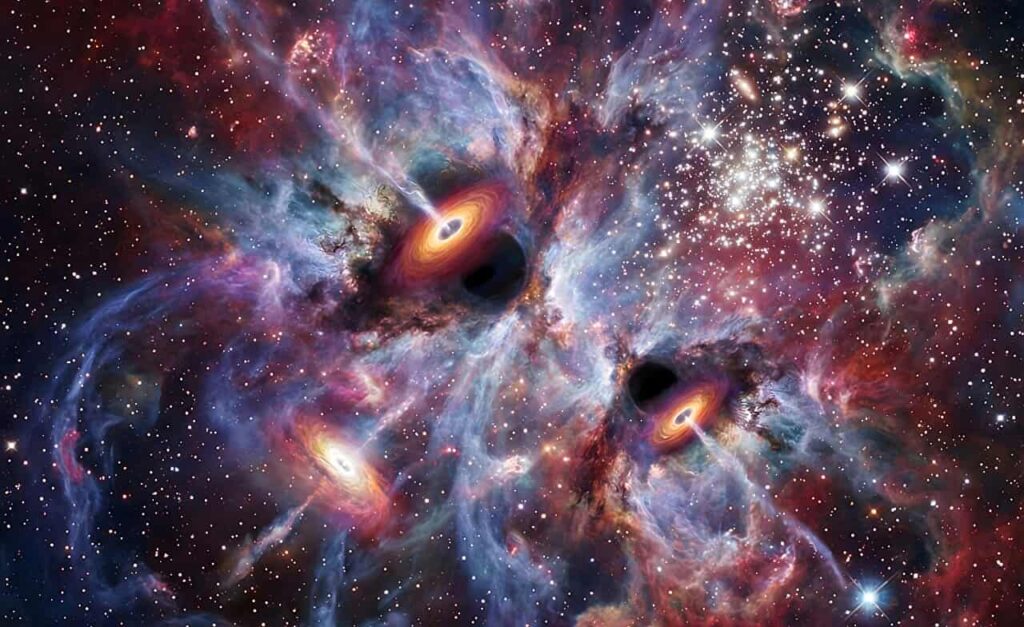

Computer visualization showing baby black holes growing in a young galaxy from the early Universe. Credit: Dr. John Regan

Computer visualization showing baby black holes growing in a young galaxy from the early Universe. Credit: Dr. John Regan

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope have spotted supermassive black holes—objects up to millions of times the sun’s mass—at times when the cosmos was still in its infancy. How did they grow so large, so fast?

A new study in Nature Astronomy argues that the early universe may have made it easier than many researchers assumed, by turning young galaxies into chaotic feeding grounds for small, newly born black holes.

“We found that the chaotic conditions that existed in the early Universe triggered early, smaller black holes to grow into the super-massive black holes we see later following a feeding frenzy which devoured material all around them,” said Daxal Mehta, a PhD candidate at Maynooth University in Ireland, in a statement.

Mehta and his colleagues reached that conclusion by running unusually sharp computer simulations of the first galaxies. In those digital universes, black holes that began as leftovers of the first generation of stars sometimes swelled to roughly ten thousand times the sun’s mass.

“We revealed, using state-of-the-art computer simulations, that the first generation of black holes—those born just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang—grew incredibly fast, into tens of thousands of times the size of our Sun,” Mehta added.

That doesn’t mean every early black hole became a titan. But the study suggests that a surprising number may have been poised to do so—if only they landed in the right cosmic neighborhood.

Black Hole Nursery

As gas falls toward a black hole, it heats up and shines. If the glow becomes intense enough, it can push incoming gas away. Astronomers call this balancing point the Eddington limit, and for decades it has served as a kind of cosmic speed limit for black hole growth.

The Maynooth team focused on “light seed” black holes. These are petite black holes born when the first stars died. In many scenarios, these seeds start at intermediate mass, and then must steadily eat for a long time to reach supermassive scale.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

In their simulations, however, some seeds surged.

The researchers modeled black holes forming from early, metal-free stars, known as population III stars, thought to be typically far more massive than most stars forming today. In the highest-resolution runs, the simulations could resolve structures down to about a tenth of a parsec—roughly the scale of the inner regions of a stellar cluster—fine enough to track dense gas flows in the immediate surroundings of a small black hole.

Finer simulations captured short, intense growth episodes that lower-resolution models fail to detect.

The study shows that these growth spurts were brief by cosmic standards, lasting roughly 100,000 to 1 million years. Yet, during the most intense bursts, some black holes pulled in gas up to a thousand times the usual limit or short periods in the simulations.

In plainer terms, the early universe sometimes let black holes break the speed limit.

Those binges depended on surroundings that were dense, cold, and slow-moving enough for gas to keep piling in. But they also faced a built-in shutoff. Explosions from nearby stars—and, in some runs, heat injected by the black hole itself—could blast the neighborhood clear, starving the black hole and ending the growth spurt.

Listening Closer

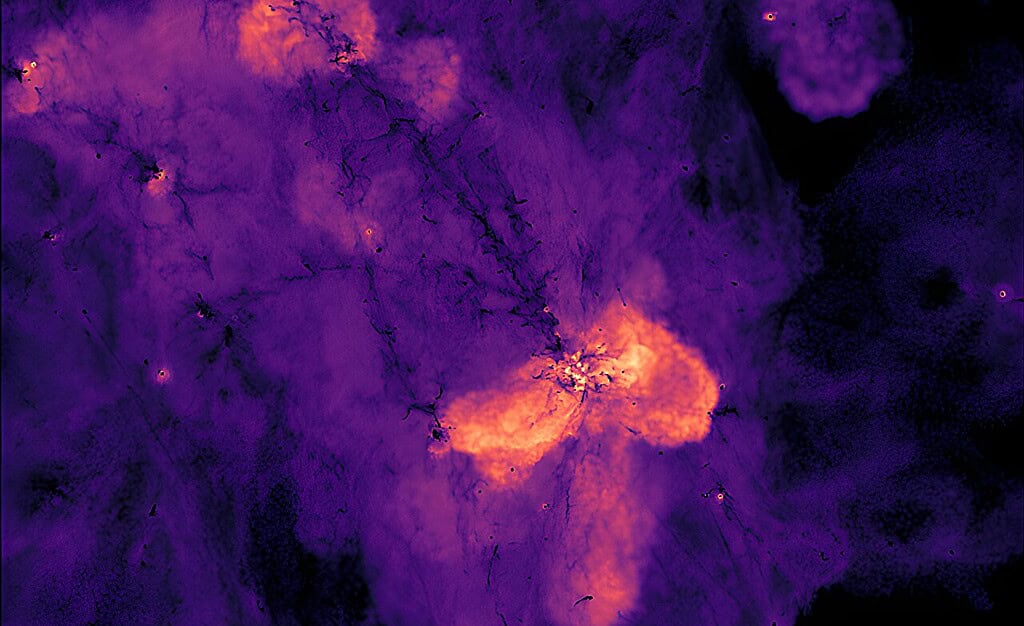

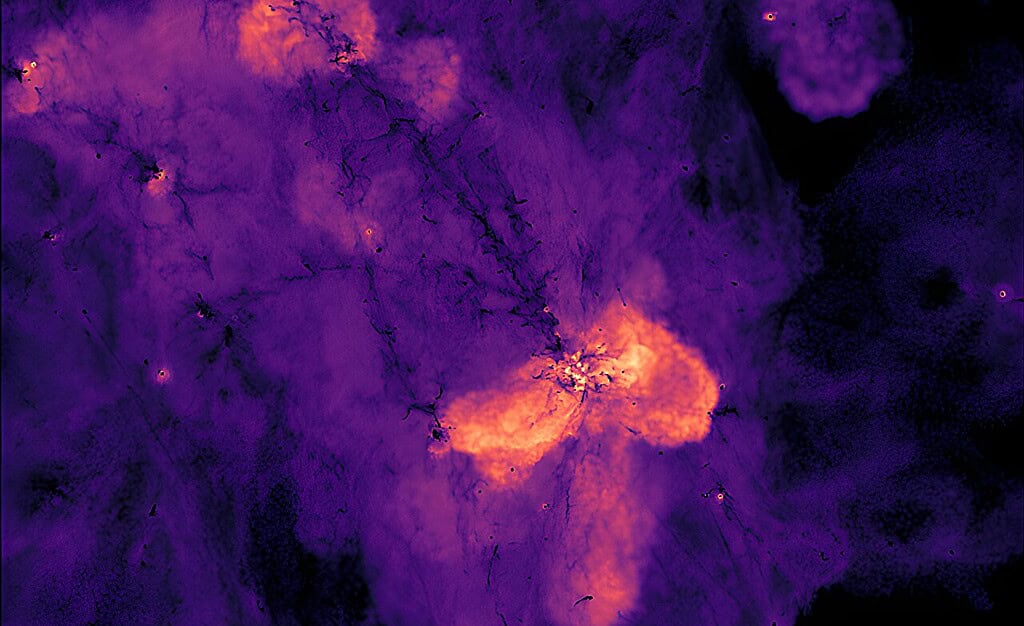

Computer-generated image showing the emergence of cosmic structure in the very early Universe. Credit: Dr. John Regan

Computer-generated image showing the emergence of cosmic structure in the very early Universe. Credit: Dr. John Regan

Previously, one common way to explain these early giants has been the idea of “heavy seed” black holes—objects born already massive, sometimes up to 100,000 times the sun’s mass. Starting big makes the puzzle of early supermassive black holes easier to explain, since there is less growth to account for.

The new simulations don’t eliminate heavy seeds. But the results weaken the assumption that heavy seeds are necessary.

“These tiny black holes were previously thought to be too small to grow into the behemoth black holes observed at the center of early galaxies,” Mehta said. “What we have shown here is that these early black holes, while small, are capable of growing spectacularly fast, given the right conditions.”

If that’s right, the early universe may have produced a broader population of mid-sized black holes, which act as stepping stones between stellar remnants and the supermassive beasts anchoring galaxies today. The simulations show several black holes growing to about ten thousand times the sun’s mass, mainly by pulling in gas rather than by merging with other black holes.

“This breakthrough unlocks one of astronomy’s big puzzles,” said Lewis Prole, a postdoctoral researcher on the team, in a statement. “That being how black holes born in the early Universe, as observed by the James Webb Space Telescope, managed to reach such super-massive sizes so quickly.”

The idea also suggests listening instead of looking—potentially through gravitational-wave signals from early black hole populations.