The Milky Way — and in fact our entire galactic neighborhood known as the Local Group — appear to be lodged in a vast, extended “sheet” of dark matter flanked on each side by cosmic voids, new research suggests.

The findings, described in a new study published in Nature Astronomy, could help explain the puzzling motion exhibited by our nearby galaxies, which seems to defy the gravitational influence of neighboring realms.

The enigma ties in with the American astronomer Edwin Hubble’s discovery nearly a century ago that the universe is expanding. The discovery was made after Hubble noticed that nearly every galaxy he observed was moving away from the Earth at a speed directly proportional to its distance.

But there was one notable exception: Andromeda, the nearest major galaxy to ours, which was instead moving towards us. This was a head-scratcher, because Andromeda, the Milky Way, and dozens of other nearby galaxies are all gravitationally bound to each other, forming what’s known as the Local Group. The immense gravity of the Local Group should, in theory, be drawing all its constituent realms towards each other, and not just Andromeda.

To take their own stab at solving this long-standing mystery in astronomy, the researchers created a “virtual twin” of the Local Group and dozens of other nearby galaxies lying beyond it by essentially simulating its evolution from scratch based on observations of the cosmic microwave background, or the leftover light from the Big Bang, allowing them to infer the eventual-group’s starting conditions. They then compared the motions of the simulated galaxies to their real life counterparts, and found that they agreed with each other.

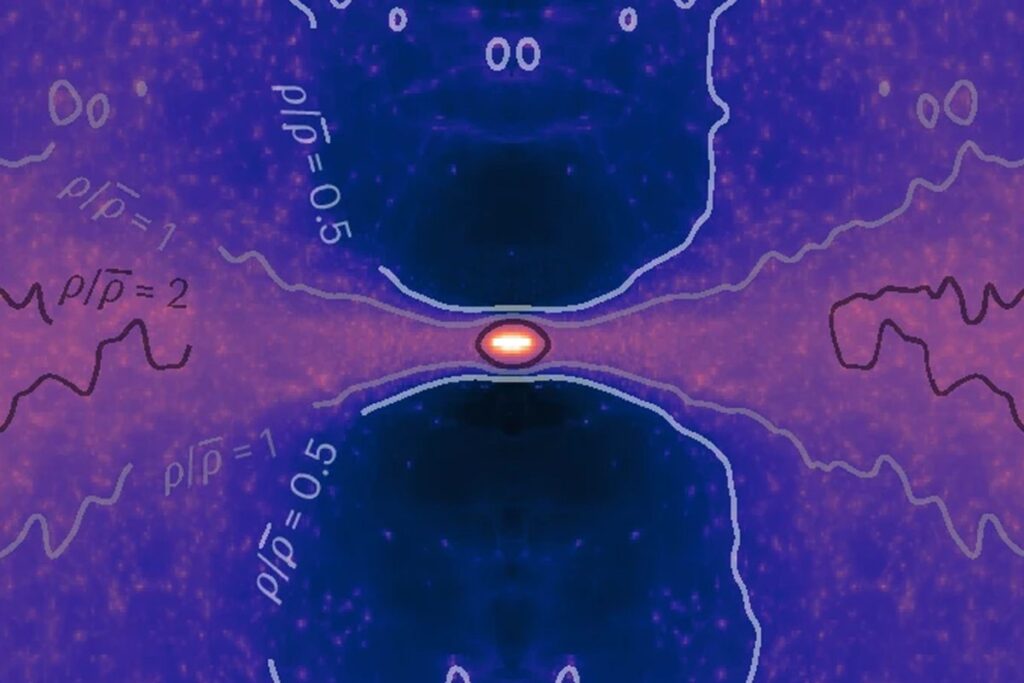

That suggested their virtual twin was on the money. And what they found was that the only way this simulation made sense was if the the entire Local Group was sitting in a huge “sheet” millions of light years across made of dark matter, the invisible and still-hypothetical substance thought to make up some 85 percent of all mass in the universe.

Astronomers first hypothesized dark matter’s existence by observing that all the visible matter that we’re seeing in galaxies wouldn’t be enough to hold them together. Dark matter provides the gravitational scaffolding necessary to keep everything in place, staying invisible and not interacting with ordinary matter. As such, the standard model of cosmology holds that entire galaxies are suspended in enormous clumps of the stuff, called dark matter halos, with perhaps trillions of times more mass than our Sun.

The thing is that these halos are traditionally thought to be giant, clumpy spheres — not a huge “sheet” as the researchers propose here. But, they argue, this flat geometry provides a tidy explanation for our runaway nearby galaxies. “In a sheet-like geometry,” the researchers explain in the study, “the velocity–distance relation depends not only on the enclosed mass, as in the spherical case, but also on the mass at larger distances.” The mass at the distant edges of the dark matter sheet, in other words, is pulling everything within it slightly outward, while beyond the plane’s boundaries lies a void where no galaxies reside.

Study lead author Ewoud Wempe of the Kapteyn Institute in Groningen, Netherlands says this is the first assessment of the distribution and velocity of dark matter in the Local Group.

“We are exploring all possible local configurations of the early universe that ultimately could lead to the Local Group,” Wempe said in a statement about the work. “It is great that we now have a model that is consistent with the current cosmological model on the one hand, and with the dynamics of our local environment on the other.”

More on space: Mind Blowing James Webb Photo Shows Star Crumbling Into Dust