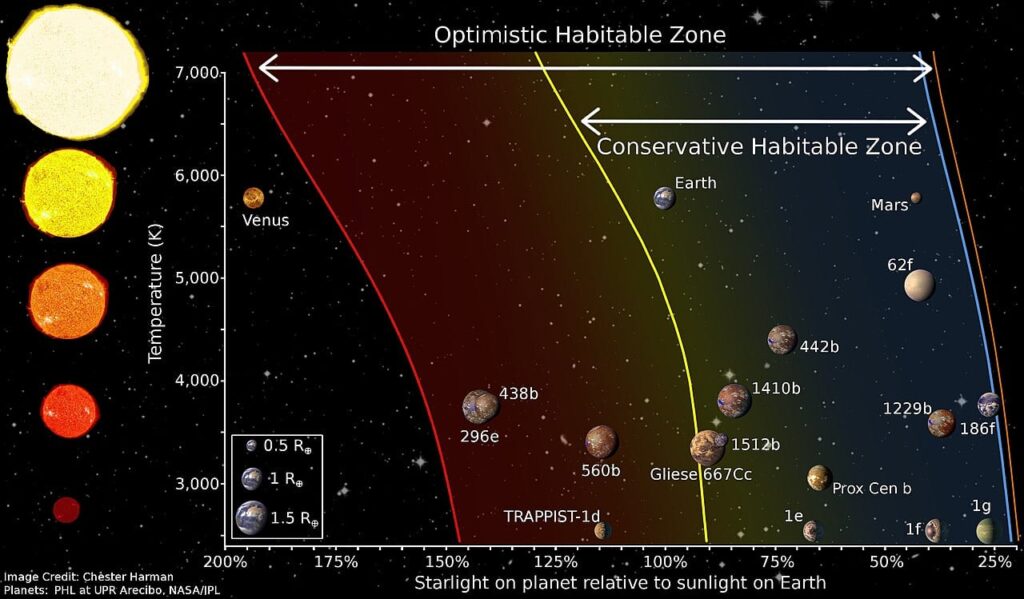

This was the most widely used diagram for explaining the Habitable Zone. Shown is temperature vs starlight received. Important exoplanets are placed on the diagram, plus Earth, Venus, and Mars. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

This was the most widely used diagram for explaining the Habitable Zone. Shown is temperature vs starlight received. Important exoplanets are placed on the diagram, plus Earth, Venus, and Mars. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Life as we know it needs liquid water. For liquid water to exist on a given planet, it has to lie in a specific region called the “habitable zone” or “Goldilocks zone”. This zone is estimated using the star’s size and the distance between the planet and the star.

But maybe we were wrong.

In research published this month in The Astrophysical Journal, the astrophysicist Amri Wandel of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem proposes that liquid water could persist on many worlds long written off as inhospitable, far beyond the Goldilocks zone.

Simply put, many more planets could be habitable.

Tidally Locked

The classic habitable zone was built with the Earth in mind: a fast-rotating planet warmed evenly by a Sun-like star. But most of the planets discovered so far orbit smaller, cooler stars. The most common example is a class of stars called M-dwarfs, or red dwarfs.

However, this means many planets are “tidally locked” with their star. Like the Earth and the moon, just one size is visible. This means one hemisphere is locked in permanent daylight, the other in endless night.

For years, this arrangement looked bleak. A scorching day side and a frozen night side doesn’t seem promising for life.

Wandel’s analysis tells a different story. Using a new climate model, he examined how heat moves across these locked worlds. He found that even modest atmospheric heat transport can keep parts of the night side above freezing. In essence, liquid water could survive even if the planet is much closer to its star than previously thought.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

This model is also backed by recent observations. The James Webb Space Telescope has recently detected water vapor and other volatile gases around several planets orbiting M-dwarfs—planets previously thought unlikely to retain such compounds.

Under the Icy Crust

The study pushes the habitable zone in both directions.

Beyond the outer edge, where planets receive little starlight, surface water should freeze. But Wandel points out that liquid water doesn’t necessarily need sunlight. Beneath thick ice layers, heat from a planet’s interior could melt ice from below, forming subglacial or intraglacial lakes.

This idea also has strong local precedents. In our own solar system, Jupiter’s moon Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus hide oceans beneath frozen crusts. Mars, too, may host pockets of liquid water trapped beneath its polar ice.

Wandel’s calculations suggest that similar environments could exist on rocky exoplanets far outside the textbook habitable zone. In these cases, water would be hidden rather than obvious, but still potentially available for chemistry associated with life.

Taken together, the inward and outward extensions radically change how astronomers decide which world deserves attention. Instead of a thin ring, habitability becomes a broad swath, defined by atmosphere, heat distribution, and internal energy as much as by distance from its star.

The study, however, does not claim that these worlds are alive, or even friendly to life as we know it. Many factors remain uncertain, from atmospheric loss during stellar flares to the chemistry of buried oceans. But by relaxing rigid assumptions, the work expands the range of environments worth investigating.

In a galaxy filled mostly with small, cool stars, that expansion matters. It suggests that the ingredients for liquid water (and perhaps for life) may be far more common we thought.