Cosmic radio pulses repeating every few minutes or hours, known as long-period transients, have puzzled astronomers since their discovery in 2022. Our new study, published in Nature Astronomy today, might finally add some clarity.

Radio astronomers are very familiar with pulsars, a type of rapidly rotating neutron star. To us watching the skies from Earth, these objects appear to pulse because powerful radio beams from their poles sweep our telescopes – much like a cosmic lighthouse.

The slowest pulsars rotate in just a few seconds – this is known as their period. But in recent years, long-period transients have been discovered as well. These have periods from 18 minutes to more than six hours.

From everything we know about neutron stars, they shouldn’t be able to produce radio waves while spinning this slowly. So, is there something wrong with physics?

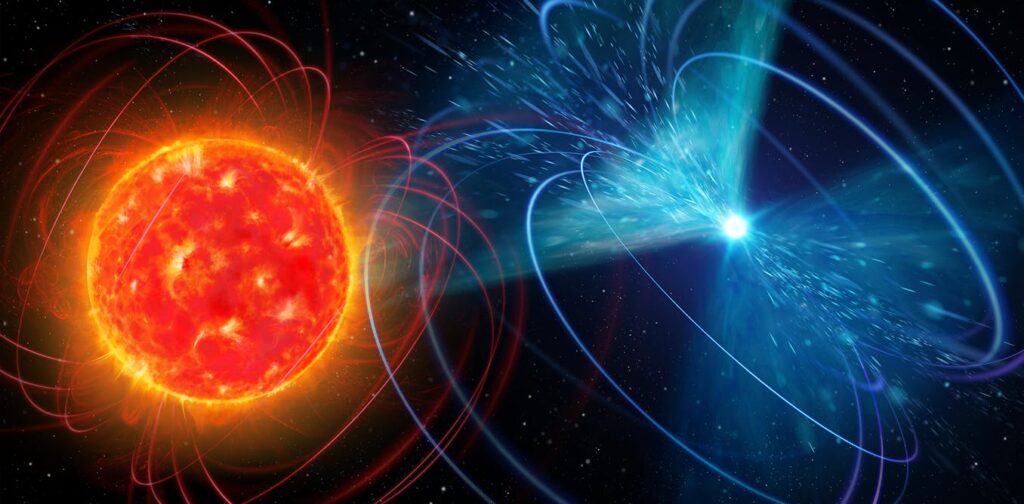

Well, neutron stars aren’t the only compact stellar remnant on the block, so maybe they’re not the stars of this story after all. Our new paper presents evidence that the longest-lived long-period transient, GPM J1839-10, is actually a white dwarf star. It’s producing powerful radio beams with the help of a stellar companion, implying others may be doing the same.

Pulsars emit powerful beams of radio waves from their poles, which sweep across our line of sight like a lighthouse.

Joeri van Leeuwen

Enter white dwarf pulsars

Like neutron stars, white dwarfs are the remnants of dead stars. They’re about the size of Earth, but with an entire Sun’s-worth of mass packed in.

No isolated white dwarf has been observed to emit radio pulses. But they have the necessary ingredients to do so when paired with an M-type dwarf (a regular star about half the Sun’s mass) in a close two-star system known as a binary.

In fact, we know such rapidly spinning “white dwarf pulsars” exist because we’ve observed them – the first was confirmed in 2016.

Which raises the question: could long-period transients be the slower cousins of white dwarf pulsars?

More than ten long-period transients have been discovered to date, but they’re so far away and embedded so deep in our galaxy, it’s been difficult to tell what they are. Only in 2025 were two long-period transients conclusively identified as white dwarf–M-dwarf binaries. This was quite unexpected.

However, it left astronomers with more questions.

Even if some long-period transients are white dwarf–M-dwarf binaries, do they radiate in the same way as the faster white dwarf pulsars? And are the long-period transients only visible at radio wavelengths doomed to be a mystery forever?

What we needed is a model that works for both, and a long-period transient with enough high-quality data to test it on.

A uniquely long-lived example

In 2023 we discovered GPM J1839-10, a long-period transient with a 21-minute period. It was the second-ever such discovery, but unlike its predecessor or those found since, it is uniquely long-lived. Pulses were found in archival data going back as far as 1988, but only some of the times that they should have been detected.

As it’s 15,000 light-years away, we can only see it in radio waves. So we dug deeper into this seemingly random, intermittent signal to learn more.

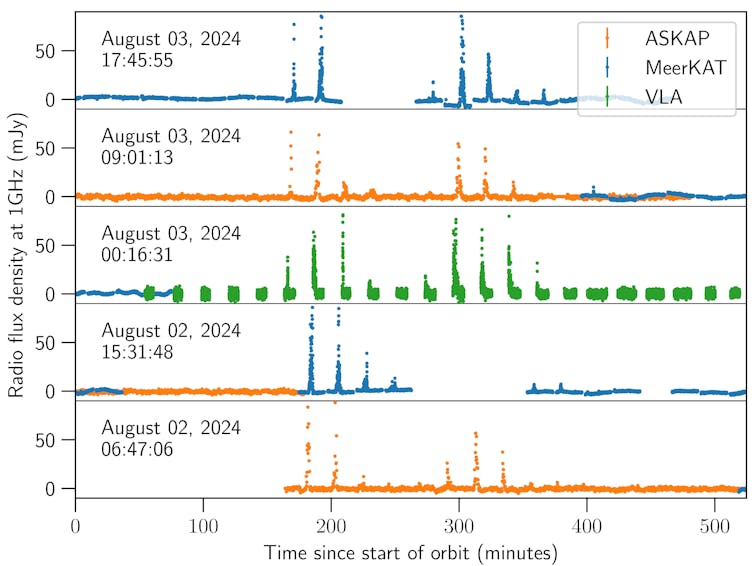

We watched GPM J1839-10 in a series dubbed “round-the-world” observations. These used three telescopes, each passing the source to the next as Earth rotated: the Australian SKA Pathfinder or ASKAP, the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa, and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array in the United States.

Radio data recorded in the ‘round-the-world’ observations. Five consecutive orbits are stacked to align the heart-beat pattern. The colour represents the telescope used.

Author provided

The intermittent signal turned out to not be random at all. The pulses arrive in groups of four or five, and the groups come in pairs separated by two hours. The entire pattern repeats every nine hours.

Such a stable pattern strongly implies the signal is coming from a binary system of two bodies orbiting each other every nine hours. And knowing the period also helps us work out their masses, which all adds up to being a white dwarf–M-dwarf binary.

Checking back, not only were the archival detections consistent with the same pattern, but we were able to use the combined data to refine the orbital period to a precision of just 0.2 seconds.

A heartbeat pattern

Radio data alone tells us GPM J1839-10 is definitely a binary system. What’s more, the peculiar heartbeat of its pulses gives clues to its nature in a way that’s only possible from looking at radio signals.

Inspired by a previous study on a white dwarf pulsar, we modelled GPM J1839-10 as a white dwarf generating a radio beam as its magnetic pole sweeps through its companion’s stellar wind. The varying alignment of the binary bodies with our line-of-sight throughout the orbit accurately predicts the heartbeat pattern.

We can even reconstruct the geometry of the system, such as how far apart the stars must be, and how massive they are.

All told, GPM J1839-10 has the potential to be the missing link between long-period transients and white dwarf pulsars.

Animation of the model. The white and red spheres are the white dwarf and M-dwarf. The arrow represents the white dwarf’s rotating magnetic moment. The yellow cone is the radio beam whose activity depends on the alignment of the white dwarf’s magnetic moment with the M-dwarf. Below is the radio flux density detected on Earth.

Author provided

Armed with our model, other astronomers have already been able to detect variability at our measured periods in high-precision optical data, despite not being able to distinguish the binary pair.

Research is ongoing on exactly how the emission physics works, and how the broader range of long-period transient properties fit together. However, this is a crucial step towards understanding.