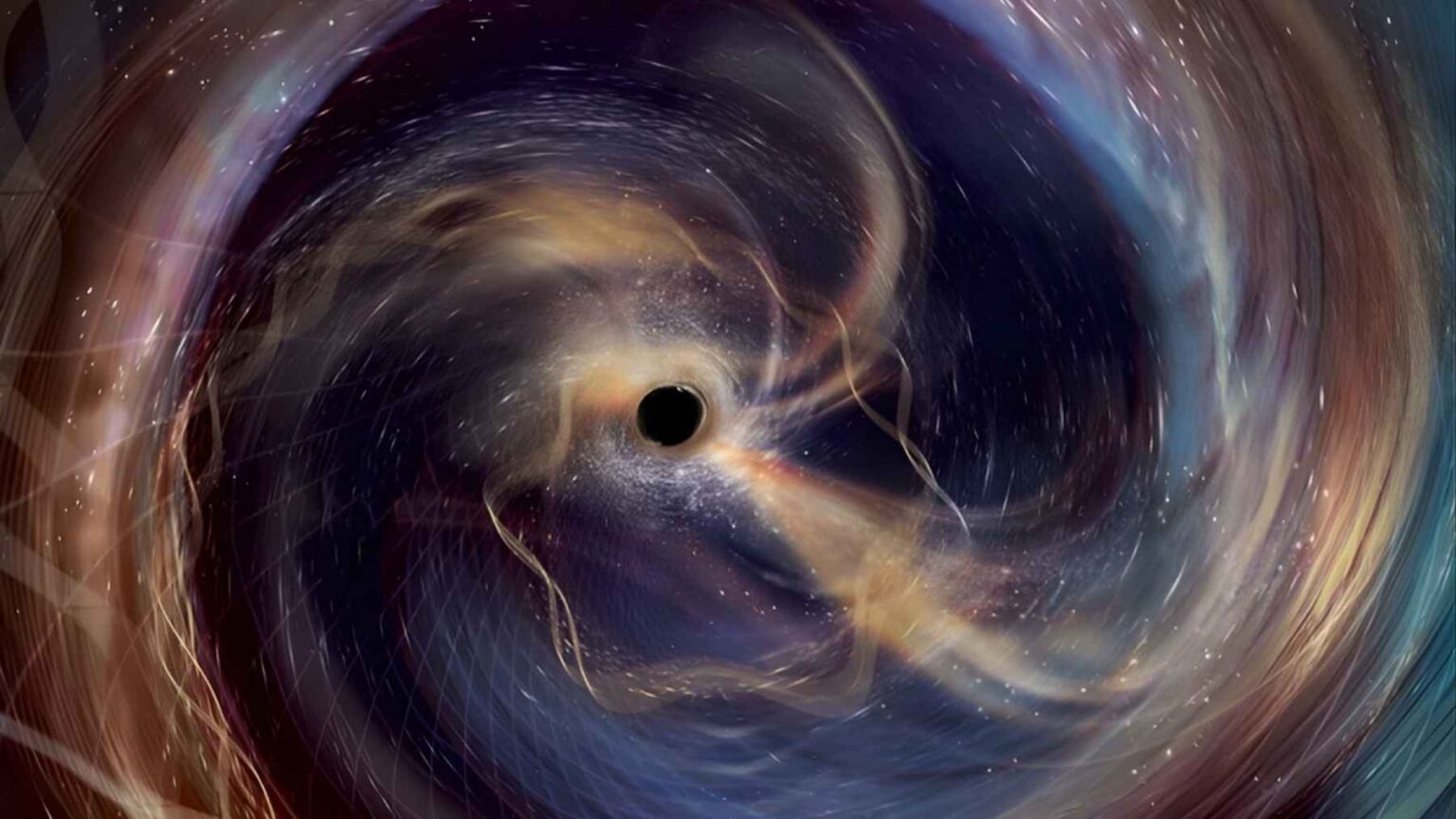

The universe has just sent its loudest gravitational whisper so far. In that tiny ripple in space time, Stephen Hawking’s black hole rule has faced its toughest test yet. What can a barely detectable shiver in space time really tell us? The signal, called GW250114, came from two black holes colliding more than a billion light years away and showed with 99.999 percent confidence that their total surface area grew instead of shrank.

Astronomers picked up this cosmic echo in January 2025 with the twin LIGO detectors in the United States. The international LIGO Virgo KAGRA team has now combed through the data and reported the result in a new study built around Hawking’s 1971 idea that black holes can only grow in area when they merge.

A new way of sensing the universe

Until a decade ago, astronomy mostly relied on light in all its forms and on a few ghostly particles. That changed in 2015, when LIGO recorded the first clear gravitational wave from two distant black holes spiraling together, opening a new window on the universe. Gravitational waves are ripples in space time itself created when massive objects crash together.

To catch those ripples, engineers built giant L shaped laser interferometers with arms four kilometers long. The passing wave stretches one arm and squeezes the other by a distance far smaller than a proton. Reaching that sensitivity takes years of work on vibration isolation, ultra-stable lasers and high-vacuum systems, quiet engineering that rarely appears in everyday headlines.

From early hint to crystal clear proof

Back in 2021, researchers used LIGO’s first signal, known as GW150914, to test Hawking’s black hole area theorem for the first time. By comparing the areas of the two original black holes with the final remnant, they found that the total area increased, but only with about 95 percent confidence. It was a strong hint, not yet a slam dunk.

GW250114 is the upgrade. It is the clearest black hole merger signal ever recorded, roughly twice as strong as the previous record holder, which lets scientists measure the masses and spins of the colliding black holes and of the final remnant with much smaller uncertainties.

Before the crash, the two black holes together had a horizon area of about 240,000 square kilometers, roughly the size of Oregon. After the merger, the new black hole‘s area grew to around 400,000 square kilometers, closer to the size of California. The increase matches Hawking’s rule, and the analysis puts the chance of a violation at less than one in one hundred thousand.

A universe that rings like a bell

Gravitational wave signals from a merger have two main acts. First comes the inspiral, a rising chirp as the black holes orbit faster and faster. Then the new black hole rings as it settles, a phase called the ringdown. In GW250114, scientists could clearly pick out two tones in that ringdown and use them to pin down the final mass and spin, finding a pattern that matches Einstein’s theory.

Why should anyone care whether a black hole’s surface area grows or shrinks if no one will ever see it directly? Hawking and his colleague Jacob Bekenstein argued in the 1970s that a black hole’s surface area reflects its entropy, a kind of cosmic disorder. If the area never shrinks, the entropy never decreases, mirroring the familiar second law of thermodynamics.

Each clean test of the area theorem therefore checks whether gravity and quantum physics still follow the same rules in the most extreme environments.

Listening even deeper

LIGO and its partners Virgo in Italy and KAGRA in Japan already detect black hole or neutron star collisions every few days, and upgrades keep pushing their sensitivity. Next generation projects like the underground Einstein Telescope in Europe and the long arm Cosmic Explorer concept in the United States aim to hear mergers from much farther away and to test gravity in more extreme regimes. Each step makes it easier to turn a faint space-time whisper into a solid number.

It may feel distant from the worries of an electric bill or morning commute, yet this kind of precise listening gradually sharpens the basic physics that underlies our technology-rich lives. It also shows how patient, long-term engineering can turn the faintest possible signals into hard data.

The study was published in Physical Review Letters.