An international team, including Cornell University researcher Jake Turner, has developed a new analysis method capable of detecting previously undiscovered signals from stars and exoplanets hidden in archived radio astronomy data. Thanks to this innovation, scientists have discovered new bursts originating from dwarf stars and, possibly, exoplanets.

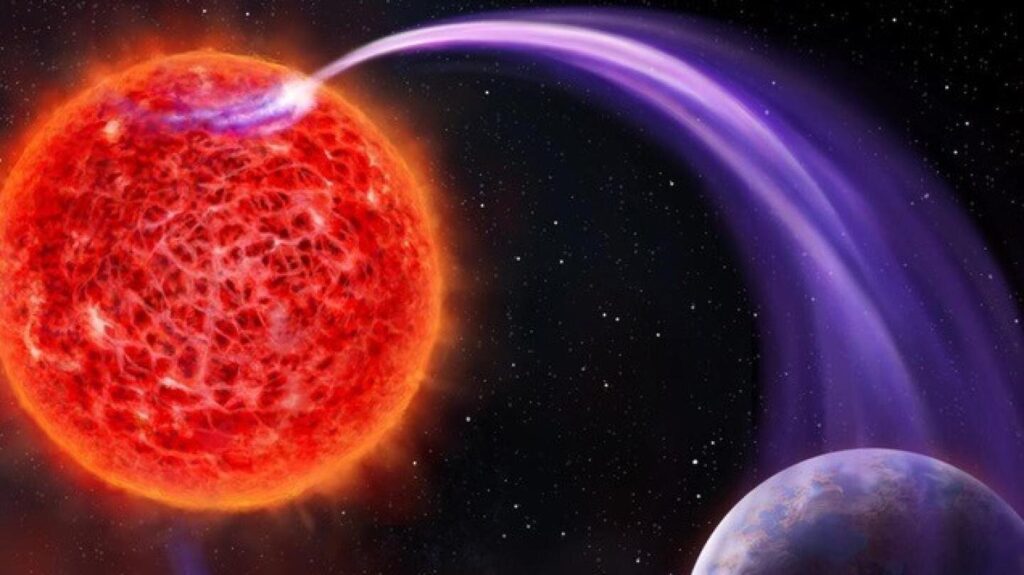

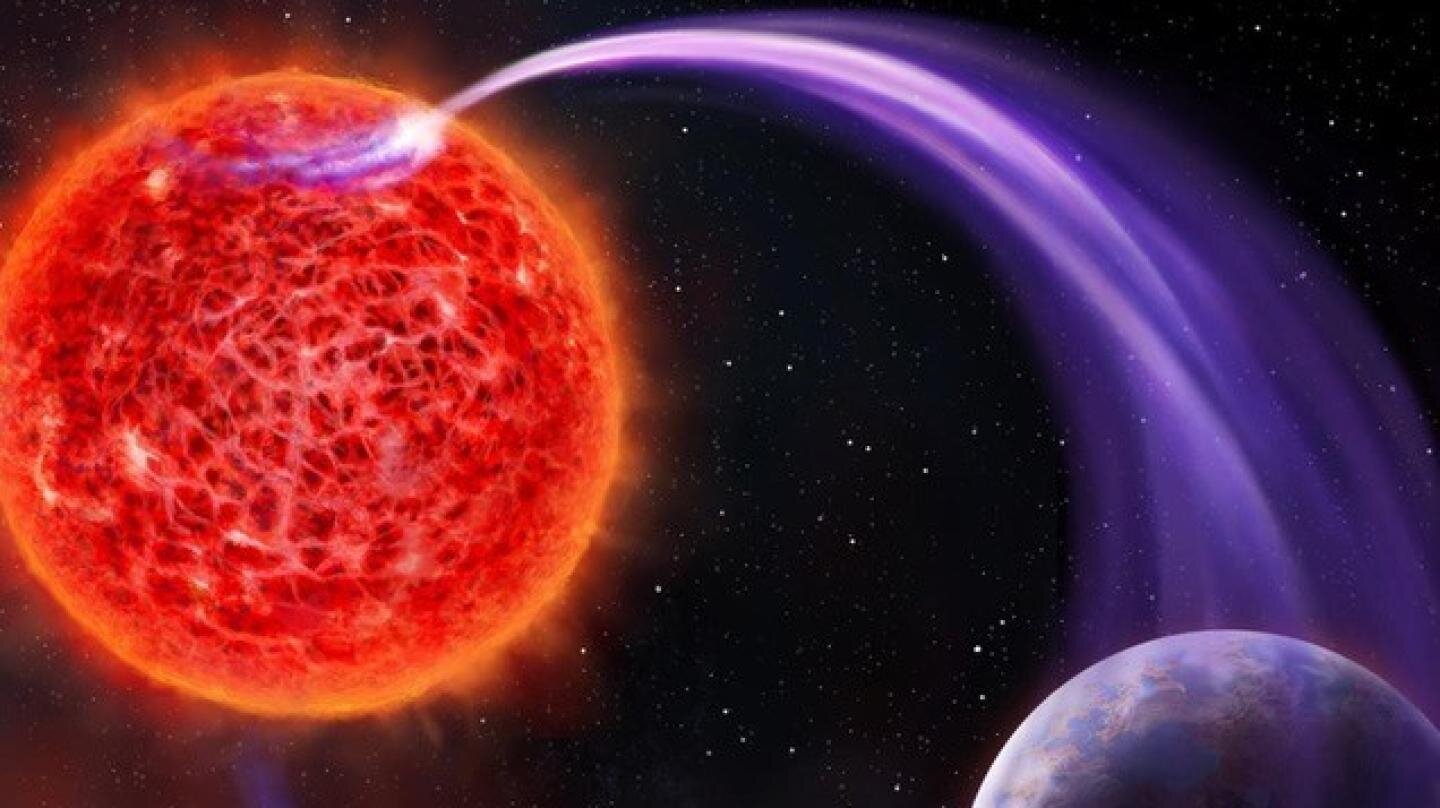

Interaction between the magnetic fields of stars and planets. Source: phys.org

Interaction between the magnetic fields of stars and planets. Source: phys.org

A new way to search in archives

Modern radio telescopes collect enormous amounts of data; synthesized images are used to study distant galaxies and black holes. Until now, these archives have never been used for minute-by-minute monitoring of the variable activity of hundreds of stars hidden in the field of view of each observation, which is made possible by Multiplexed Interferometric Radio Spectroscopy (RIMS). This method turns each radio observation into a simultaneous study of hundreds or even thousands of stars, like a net that catches many fish where a single rod would catch only one.

Scientists say that without the new method, it would take nearly 180 years of dedicated observation to achieve the same level of detection.

By applying RIMS to data collected by the European LOFAR radio telescope over more than 1.4 years as part of the extensive LoTSS astronomical survey, the team obtained at least 200,000 dynamic spectra of isolated stars or stars with exoplanets. Among the signals detected by RIMS are bursts corresponding to violent events similar to solar coronal mass ejections.

Signals from the magnetic fields of exoplanets

Even more remarkably, some signals demonstrate all the expected characteristics of magnetic interactions between stars and planets, a mechanism comparable to the one that causes certain auroras on Jupiter, the researchers note.

These radio signals may be among the first reliable evidence of magnetic interactions between stars and exoplanets, as well as the existence of exoplanetary auroras, indicating the likely existence of exoplanetary magnetospheres, said Turner, a research associate in the Cornell Center for Astrophysics and Planetary Science and a member of the Carl Sagan Institute, in the College of Arts & Sciences.

“Exoplanets with and without a magnetic field form, behave and evolve very differently. Therefore, there is great need to understand whether planets possess such fields. Most importantly, magnetic fields may also be important for sustaining the habitability of exoplanets, such as is the case for Earth,” Turner said.

Expanding the scope of RIMS

The breakthrough of RIMS opens up new possibilities for low-frequency radio astronomy, as RIMS effectively turns each group of radio telescopes into a powerful detector of variable radio signals from nearby stars. The new technique was successfully applied to the new French low-frequency radio telescope NenuFAR and enabled the detection of a burst from a star-planet system. This article, co-authored by Turner, was published last year in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

“This study with NenuFAR could represent only the second ever direct detection of radio emission from an exoplanet, following my earlier discovery of radio emission from Tau Boötes, which was the first such possible detection,” Turner said. “We are now pursuing targeted follow-up observations to confirm the planetary origin of both signals. A confirmed detection would provide a powerful new way to probe an exoplanet’s magnetic field.”

Future ground-based, space-based, and lunar radio telescopes will be able to use this new technology and are expected to detect thousands of new radio signals, paving the way for large-scale statistical studies of stellar radio emissions and the interactions between stars and planets in our galactic neighborhood.

According to phys.org