Here in our isolated corner of the Universe, we don’t normally think about all the objects, particles, and photons that miss us, even though we know they’re ubiquitous out there. Instead, all that we observe are the ones that arrive here: on Earth, in our detectors, in our telescopes, and even in our eyes. There are plenty of objects out there whose light is on the way, but hasn’t reached us just yet: objects beyond our current cosmic horizon, but not our future visibility limit. Additionally, there are massive engines out there black holes and neutron stars chief among them that accelerate particles to incredible energies: energies far greater than we could ever hope to produce in terrestrial laboratories.

But only very rarely do they interact with Earth, and produce signatures that we can actually observe. Back in 1991, the Fly’s Eye camera in Utah detected what was, at the time, a uniquely energetic event: a signature of an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray that was so far above the theoretical maximum, it created a mystery that lasted for decades. Known ever since as the Oh-My-God particle, it remains the highest-energy particle event ever observed, but has since been joined by many comparable ones. It led our reader Barret Swims to send in the following question:

“What would happen if the Oh-My-God Particle hit me square on the head? Would I spontaneously combust?”

The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is “less than you think.” Even though these cosmic rays contain enormous amounts of energy, the damage even the most energetic one could do to you is exceedingly minimal. Here’s the science behind it.

By taking a hot air balloon up to high altitudes, far higher than could be achieved by simply walking, hiking, or driving to any location, scientist Victor Hess was able to use a detector to demonstrate the existence and reveal the components of cosmic rays. In many ways, these early expeditions, dating back to 1912, marked the birth of cosmic ray astrophysics.

Credit: VF Hess Society, Schloss Pöllau/Austria

Humans remained blissfully ignorant of cosmic rays for a long time: up until the early 20th century. It was at that time that a combination of:

aviation technology, in the form of hot air balloons,

and curiosity, in the form of particle detectors/detector chambers (originally, in 1912, a simple charge-measuring instrument known as an electroscope was the very first),

led us to first detect these cosmic particles that bombard the Earth. Coming from both the Sun and also omnidirectionally from elsewhere across the Universe, these cosmic rays all behaved the same way normal particles do on Earth, except were at significantly greater energies. In addition, some of those cosmic rays didn’t match the known particles like protons, electrons, and other atomic nuclei, but included exotic particles that were being seen for the first time: positrons and muons, for example.

The muon was a particularly strange occurrence: a heavier cousin of the electron but still a fundamental particle all unto itself, it has a mean lifetime of a mere 2.2 microseconds. Even with the help you get from Einstein’s special relativity and the phenomenon of time dilation, there’s no way a muon could survive the journey from the Sun to the Earth at the energies they were observed to have, much less from farther away across the Universe. The only viable explanation is that an even higher-energy particle — a more stable one — must have struck the upper atmosphere of the Earth and produced a particle shower, where those decaying particles led to the presence of these muons. First found in the 1930s, this interpretation was later validated by a wide variety of laboratory experiments.

The first muon ever detected, along with other cosmic ray particles, was determined to be the same charge as the electron, but hundreds of times heavier, due to its speed and radius of curvature. The muon was the first of the heavier generations of particles to be discovered, dating all the way back to the 1930s.

Credit: P. Kunze, Zeitschrift für Physik, 1933

To measure these cosmic rays, we can not only set up particle detectors on Earth, high up in the atmosphere, and even directly in space, although we certainly do all of those things. In addition, we can build several different types of detectors here on Earth’s surface.

We can build large-area arrays of particle detectors, seeking to detect as many of the particles that a cosmic ray shower produces (when it strikes the upper atmosphere), as well as the decay products of those particles, down on the ground.

We can build large water tanks here on the ground, noting that the high-energy particles that pass through them will be moving faster than the speed of light in the medium of water, and therefore will produce a special kind of blue light known as Čerenkov (or Cherenkov) radiation. With radiation detectors lining the insides of those tanks, the properties of the incoming particles can be reconstructed.

And finally, we can look for that same Čerenkov radiation due to cosmic rays interacting with the Earth’s atmosphere. The Earth’s atmosphere may be thin and sparse, but it’s still a medium, and if a particle strikes that atmosphere moving faster than 99.97% the speed of light in a vacuum, it’ll be moving faster than the speed of light in the medium of Earth’s atmosphere, and hence will produce that characteristic cone of blue light. By building arrays of outdoor telescopes that gather and focus that blue light, these Čerenkov telescopes can help us reconstruct the original direction and energy of these ultra-fast cosmic rays that strike and interact with Earth’s atmosphere.

This animation showcases what happens when a relativistic, charged particle moves faster than light in a medium. The interactions cause the particle to emit a cone of radiation known as Cherenkov radiation, which is dependent on the speed and energy of the incident particle. Detecting the properties of this radiation is an enormously useful and widespread technique in experimental particle physics, and also in astronomy for detecting atmospheric cosmic rays.

Credit: Public domain image from Vlastni Dilo & H. Seldon

What we’ve discovered from this is profound. We’ve determined that there aren’t just cosmic rays striking Earth, but that those particles come with a particular flux (or rate of particle impact) that’s energy-specific, with a spectrum of cosmic rays ranging from low to intermediate to high to ultra-high to extremely high energies. Whereas terrestrial particle accelerators can take us up to tremendous energies, accelerating protons to 99.999999% the speed of light — giving them a kinetic energy that equates to some ~7000 times their rest-mass energy — cosmic rays routinely go well above that. In fact, the ultra-high and extreme energy ones, at the absolute maximum, possess millions of times the energy that the Large Hadron Collider achieves at its maximum.

However, even in theory, there’s a limit to how energetic any particle traveling through the Universe can be: the Greisen-Zatsepin-Kuzmin (or GZK) cutoff. The reason for this cutoff is straightforward: the CMB, or cosmic microwave background, exists. As particles travel through the Universe, and in particular through the empty void of the intergalactic medium that all extragalactic signals must travel through, they encounter that thermal bath of radiation left over from the Big Bang. Above some critical energy threshold, interactions between those photons and a cosmic ray will be energetic enough that additional particles, like pions, will spontaneously be created. That sets a maximum sustainable energy scale for the proton to be 5 × 1019 electron-volts. Above that, no cosmic rays at all were expected.

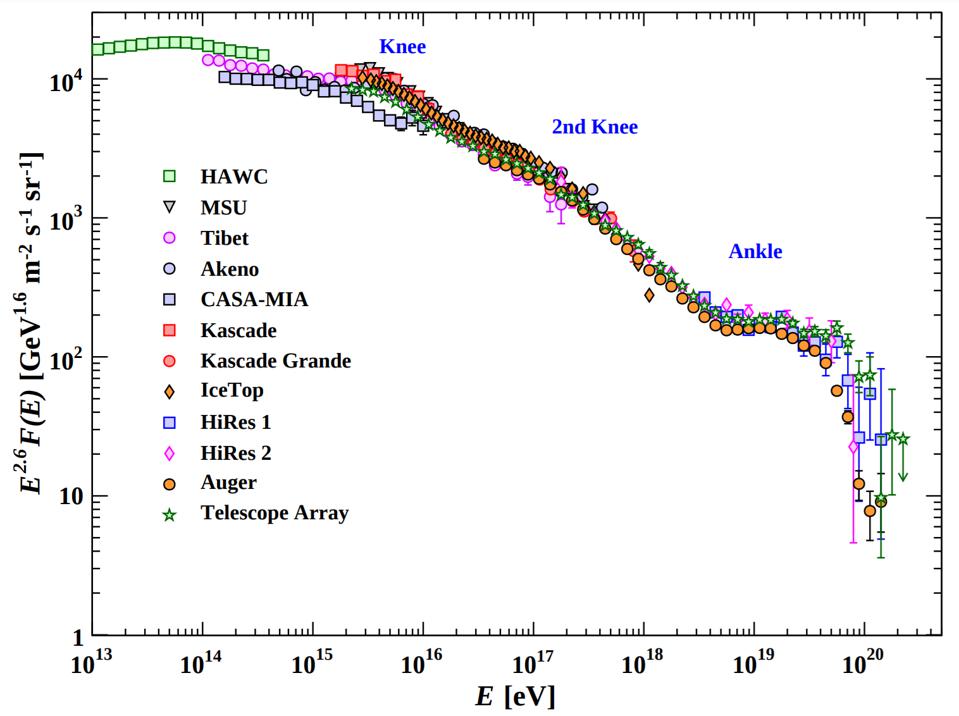

The energy spectrum of the highest energy cosmic rays, by the collaborations that detected them. The results are all incredibly highly consistent from experiment to experiment, and reveal a significant drop-off at the GZK threshold of ~5 x 10^19 eV. Still, many such cosmic rays exceed this energy threshold, indicating a flaw in the most simplified picture of these cosmic rays.

Credit: M. Tanabashi et al. (Particle Data Group), Phys. Rev. D, 2019

That’s why, when a cosmic ray array in Utah known as the High Resolution Fly’s Eye Camera began operating in 1981, they were very curious to actually begin measuring the cosmic ray spectrum. Indeed, at greater and greater energies, the flux of cosmic rays began to drop, and features that became known as the “knee,” the “second knee,” and the “ankle” appeared in the data. But then, in 1991, a huge surprise arrived: an event that was far more energetic than the GZK cutoff would allow. It swiftly became known as the Oh-My-God particle, with an inferred energy of 3.2 × 1020 electron-volts: more than six times as high as the GZK cutoff.

Originally, this was a great mystery, as cosmic rays were known to be composed almost exclusively of protons, and the theoretical limit on a proton that traveled through intergalactic space should forbid such excessively high energies. With modern data from a variety of observatories:

we now know that cosmic rays exceeding the GZK cutoff are indeed copious; we’ve seen dozens or even hundreds of such events. However, we no longer think this poses a problem for physics: either for relativity or the origin of such cosmic rays.

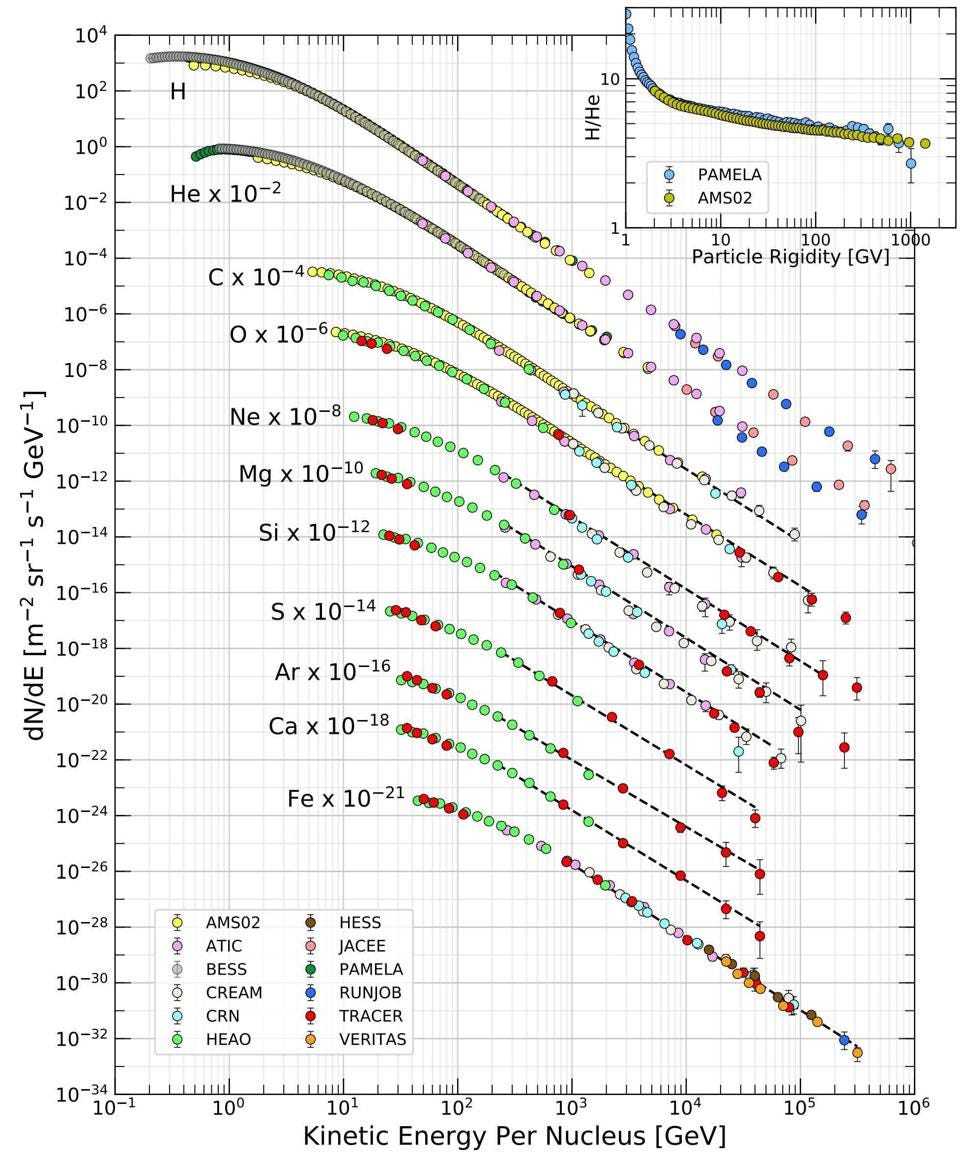

Cosmic ray spectrum of the various atomic nuclei found among them. Of all the cosmic rays that exist, 99% of them are atomic nuclei. Of the atomic nuclei, approximately 90% are hydrogen, 9% are helium, and ~1%, combined, is everything else. Iron, a low-abundance but important example of the heavy, high-energy atomic nuclei found, may compose the highest-energy cosmic rays of all: found with up to 10^11 GeV of energy.

Credit: M. Tanabashi et al. (Particle Data Group), Phys. Rev. D, 2019

Instead, we’ve measured the abundances of various types of cosmic rays, and have learned that while about 90% of them are protons, another 9% are helium nuclei (α particles), with electrons and positrons making up the remaining 1%, there’s also a very slight contribution from even heavier nuclei, going all the way up to iron nuclei, that make up the remainder of cosmic rays. However, for the extremely high-energy ones, protons become rarer and heavier nuclei become more common, solving that puzzle: the highest energy cosmic rays obey the GZK cutoff, because that cutoff is per particle. So long as the Oh-My-God particle was a carbon (or heavier) nucleus, there’s no longer a puzzle to how particles achieve such high energies and how those particles make it to Earth.

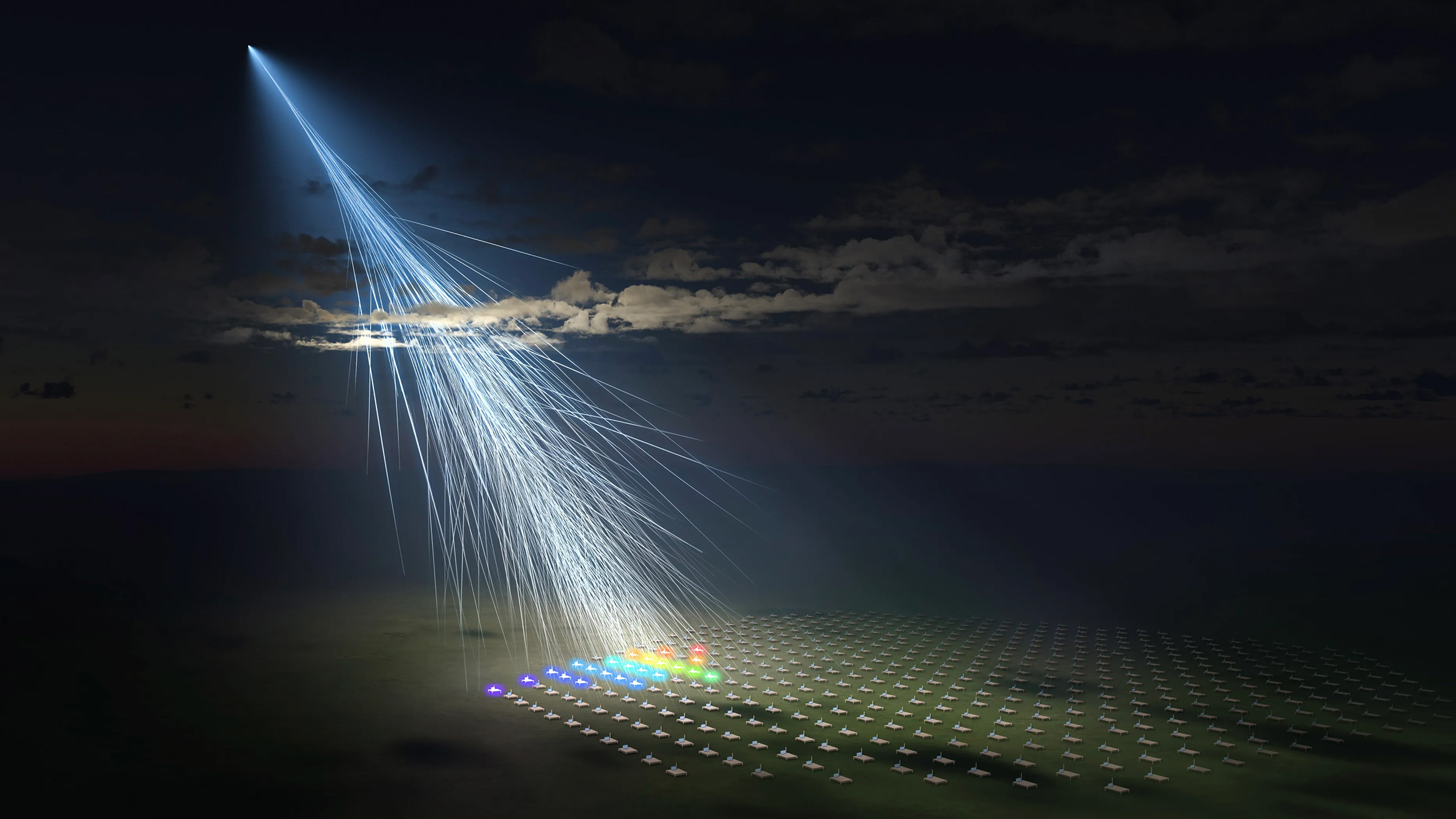

If you want to ask what would happen if the Oh-My-God particle hit you, on your head or anywhere else, where we should begin is by learning what actually happened (and happens) when such particles impact our planet in the first place. When that Oh-My-God particle hit Earth, it didn’t come all the way down to the surface intact. You have to remember that all particles have cross-sections: a physical “size” that has a probability of interacting/colliding with all other particles that have finite physical sizes. Even though Earth’s atmosphere is sparse, it’s still made of atoms, and atoms have atomic nuclei. The Oh-My-God particle first interacted with an atomic nucleus in the upper atmosphere, producing a series of daughter particles that each maintain a fraction of the original particle’s momentum, which then collide with greater and greater numbers of particles, and so on. What strikes Earth’s surface isn’t a single particle, but rather thousands of particles (and billions of Čerenkov photons), and those are the signals we can actually detect.

When high-energy cosmic particles strike the top of Earth’s atmosphere, they produce showers of “daughter” particles that will find their way down to Earth. On the surface, we’ve built several notable detector arrays, including the Pierre Auger Observatory and the Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO), to reconstruct the energy and direction of the initial cosmic ray that struck the Earth.

Credit: Osaka Metropolitan University/L-INSIGHT, Kyoto University/Ryuunosuke Takeshige

For instance, when our Čerenkov telescopes detect a signal, we can use the flux, energy, and direction of the collected photons to reconstruct what the energy of the original incoming particle was; that’s how the Fly’s Eye Experiment determined that the energy of the Oh-My-God particle was 3.2 × 1020 electron-volts (320 EeV), and the limitations of that technology is also why there was about a 30% error/uncertainty on that figure. However, we know that the Oh-My-God particle wasn’t unique, as a 213 EeV particle was discovered in 1993, a 240 EeV particle was spotted in 2021, and a 280 EeV particle was observed in 2001. The Oh-My-God particle is still the single highest-energy cosmic ray event ever seen as of 2026, but it has plenty of company.

So let’s play “what if?” What if the Oh-My-God particle really did have the reported energy of 320 EeV, and what would happen if it struck you? In particular, what would happen if it struck you, as was originally asked, right on top of your head?

As is accurately illustrated, above, if you were still at the surface of Earth and the Oh-My-God particle came in and struck the top of the planet’s atmosphere before striking you, it would only be a small fraction of “daughter” particles, descendants of the original particle that hit the upper atmosphere, that struck you. They’d have only a fraction of the energy that the original particle did, and it would cause less damage to your cells than an X-ray scan at the dentist or at the airport. In other words, simply by remaining on Earth’s surface, you’re safe from even the most energetic of cosmic rays.

On Feb. 12, 1984, astronaut Bruce McCandless ventured farther away from the confines and safety of his ship than any previous astronaut had ever been. This space first was made possible by a nitrogen jet propelled backpack. The contrast between the safety and the life-giving nature of Earth and the lifeless abyss of deep space appears in stark relief in this image. While Earth’s curvature can be seen easily, the fragility of humanity and the hostility of the environment of space are both apparent in this iconic photo, taken during a Space Shuttle Challenger mission.

Credit: NASA/STS-41B

However, if you went up into space, all of that protection imparted by Earth’s atmosphere would vanish. It would be as though all of the energy in each individual particle would begin its particle shower — would begin interacting with matter — with you: as soon as it hit your body. Back in the early days of accelerator physics, when physicists were only achieving modest levels of energy-per-particle (and also, importantly, were only sending a small number, or low-luminosity, of particles at once), there was actually a “trick” people would use to see if the beam was on. (Don’t try this at home!) They would:

close one eyelid,

position their head in the area where the beam should be traveling through,

and see if “flashes of light” would appear in your closed eye.

These particles would travel through the vitreous humor fluid in one’s eye, where they’d move faster than light in that medium, and emit Čerenkov radiation. That radiation, a mix of ultraviolet and visible light, is detectable by the human retina, and so even with your eye being closed, you could see it.

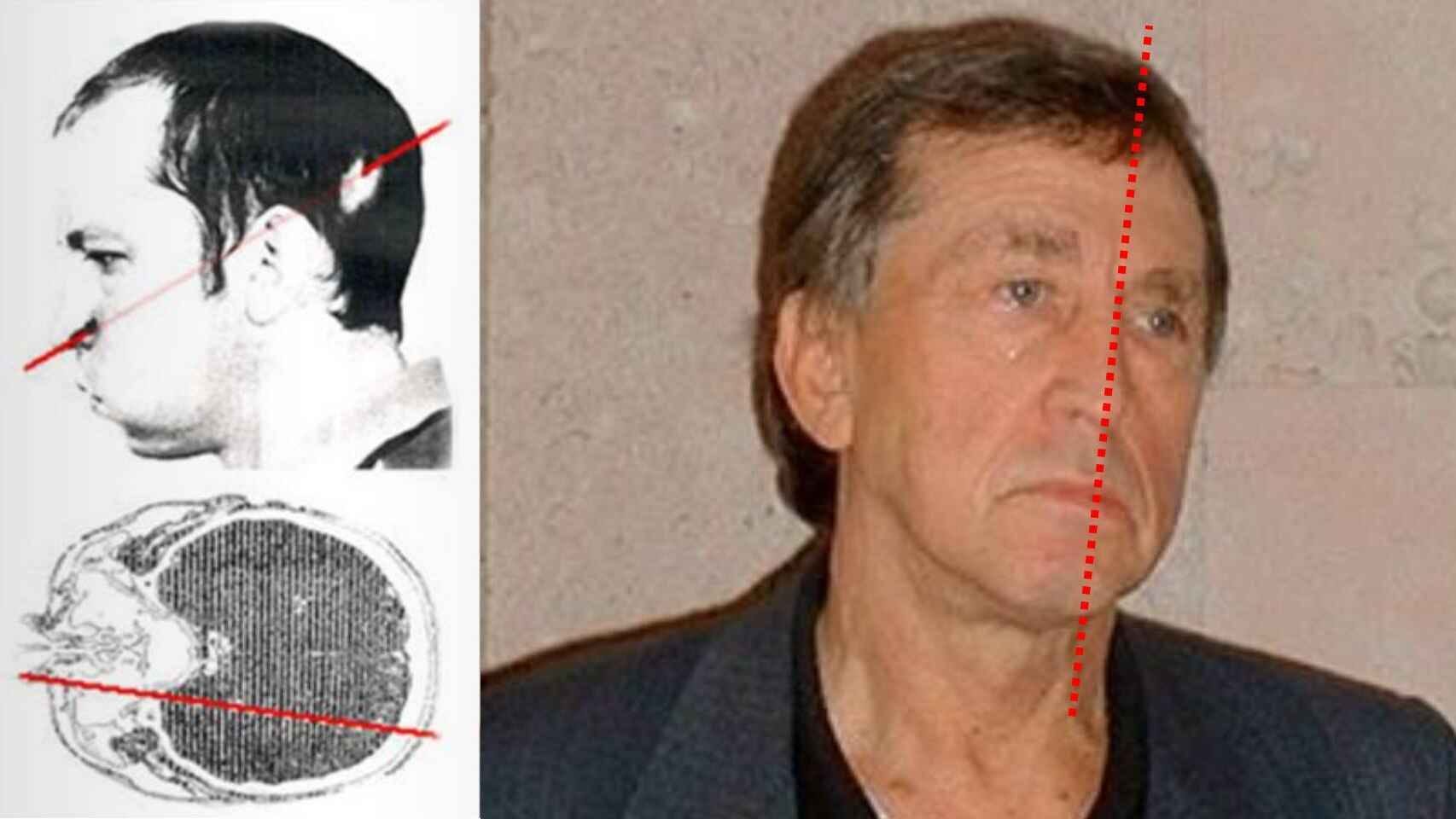

If you’ve ever heard the story of Anatoli Bugorski, whose head accidentally got exposed to a much more modern, high-energy, high-luminosity particle accelerator (in 1978), causing profound long-term damage and giving him a severe dose of radiation. However, the damage that he sustained had everything to do with the (enormous!) number of particles that struck him at once, not with the energy of the particle.

In 1978, Soviet physicist Anatoli Bugorski was working at the U-70 synchrotron: the largest particle accelerator in the USSR. As the person responsible for maintaining and operating the accelerator, the beam was turned on while he was servicing it. The left half of his face became paralyzed, but Bugorski survived and lived a mostly normal life, despite receiving a very target dose of radiation that was hundreds of times the normal fatal dose. As of 2026, he remains alive.

Credit: USSR/Mira Radiation Safety

Even with extreme energies, if it were only one single particle, only a small amount of the total energy would be deposited into your body. Sure, the effects would be concerning:

electrons would be kicked out of their atomic/molecular orbitals,

ions and free radicals would be created inside of your body,

DNA strands would be broken,

proteins and enzymes would be denatured,

and so on. However, most of the energy in that single particle — even though it’s the equivalent of a baseball thrown at top speed by a very talented middle schooler — would not get deposited in your body. It would only have the same effect that a “streak of ionizing radiation” would have as it went through your body.

Sure, there would be significant amounts of cellular death that occurred, and it would contribute very slightly to your overall lifelong risk of developing cancer. But most of the energy would still be carried by those very fast, ultra-relativistic particles once they left your body; only a small amount of energy would actually get deposited in the cells, molecules, atoms, and particles composing your body itself. For individual cellular damage, your body either repairs it or destroys the cell and replaces it. If either the main particle or a daughter particle spawned from the particle shower in your body passed through your eye, you might see the Čerenkov light from it, but there are no other circumstances that would even enable you to detect that such an event had occurred.

This photo shows a Proton Therapy treatment room, complete with the table that holds the patient, the compact particle accelerator that delivers the protons, and the ability to target specific locations where cancer tumors, and not healthy tissue, will be impacted by those accelerated protons.

Credit: Romina.cialdella/Wikimedia Commons

However, there is a very cool application of this effect: targeted cancer treatments now include things like neutron therapy and proton therapy, which can very accurately target cancer tumors while leaving the surrounding healthy tissue undamaged. It cannot rely on just one particle of extremely high energies, but rather works because enormous numbers of particles within a specific energy range — a range designed to disrupt cancer tumors specifically — is used. These therapies are not universally successful, of course, but can often save lives and defeat cancers where other methods are unsuccessful.

It’s weird to think that even the most energetic known particle in the Universe, one moving so fast that if you raced it to the Andromeda galaxy and back against a beam of light, it would only lose by a few proton widths, wouldn’t even be detectable by you if it struck you, unless it happened to produce a visual signal in your closed eyeball. Astronauts in space, likewise, lack the protection of Earth’s atmosphere, and are struck by roughly 5000 cosmic ray particles per second, feeling absolutely none of them.

In other words, getting hit by the single most energetic particle presently known in all the Universe would have no noticeable effect on you at all. The worst case scenario, perhaps ironically, would be if you were a robot or a computer, as even single bit glitches are incredibly notable across a wide variety of applications, from essential spacecraft functions to the infamous Super Mario 64 speedrun that was enhanced by a cosmic ray event that flipped a critical bit. Being a self-repairing sack of meat, even in 2026, still has its advantages.

Send in your Ask Ethan questions to startswithabang at gmail dot com!