Right after the Big Bang, the universe existed as an ultra-hot, ultra-dense fluid made of quarks and gluons, the most basic building blocks of matter. Known as quark-gluon plasma, it can be imagined as the universe’s original soup, a chaotic broth where particles moved freely before settling into the familiar matter we know today.

That state of matter survived for only the universe’s first microseconds. By recreating it in particle collisions, physicists can directly study how matter behaved at the very beginning of cosmic history. In a new experiment published in Physics Letters B, researchers tracked what happened when a single quark sped through this recreated plasma. Instead of slipping through unnoticed, the quark left behind a measurable wake, offering the clearest evidence yet that quark-gluon plasma flows and responds like a liquid.

“Quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup,” said Yen-Jie Lee, a professor of physics at MIT, in a press release.

Read More: The Universe Started as a “Hot Soup of Particles and Photons” 13.8 Billion Years Ago

Recreating Quark-Gluon Plasma at CERN

Quark-gluon plasma no longer exists naturally, but physicists can briefly recreate it using particle accelerators. At the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN), scientists use the Large Hadron Collider to smash heavy atomic nuclei together at nearly the speed of light. For an instant, these collisions melt ordinary matter into a tiny droplet resembling the universe’s earliest substance.

Although these droplets last for only a fraction of a second, they are hot and dense enough to reveal how matter behaves under extreme conditions. Over the past two decades, experiments have shown that this early-universe material does not act like a loose collection of particles. Instead, it moves as a connected whole.

That realization suggested quark-gluon plasma behaves more like a liquid than a gas, but it also raised a central question. If this primordial matter really flows, how does it respond when a single particle cuts through it?

Finding a Way to See a Single Quark

Answering that question has been difficult because particle collisions are chaotic. Quarks are usually produced in pairs that fly off in opposite directions, and their overlapping effects blur the plasma’s response.

To overcome this, researchers from MIT and their collaborators focused on rare collisions that also produce a Z boson, a particle that passes through quark-gluon plasma without noticeably interacting with it.

When a quark and a Z boson are created together, they travel in opposite directions. The Z boson acts as a clean marker, revealing the quark’s path without disturbing the surrounding plasma. Any disturbance observed on the opposite side can therefore be traced back to the quark alone.

Using data from the CMS experiment, one of the Large Hadron Collider’s main particle detectors, the team identified about 2,000 events that fit this pattern.

A Wake in the Primordial Soup

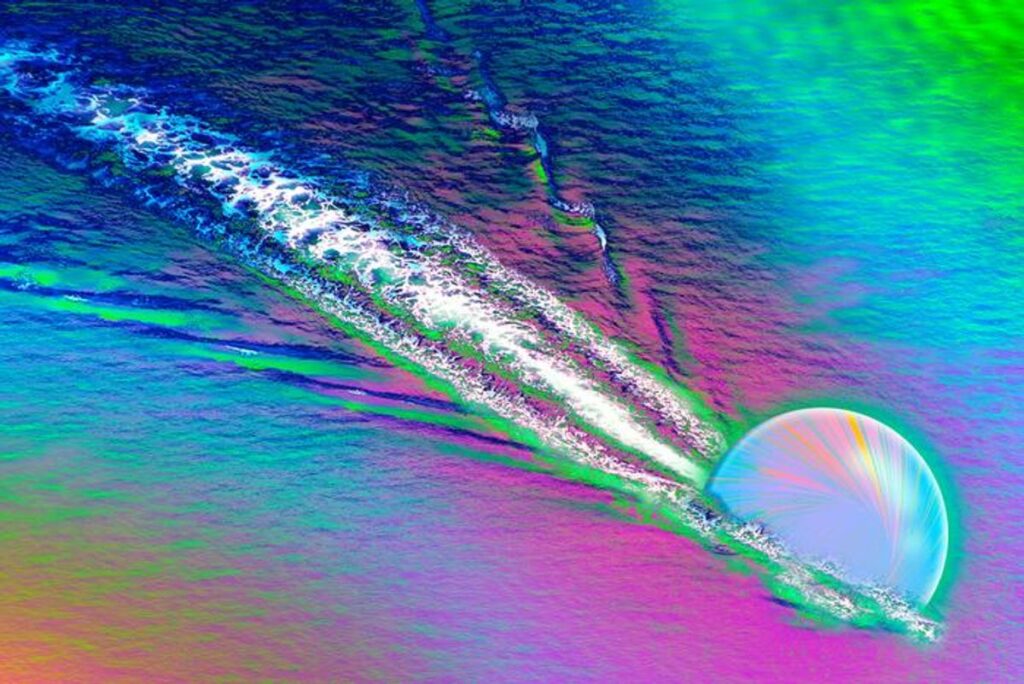

Those events revealed a consistent signal. As a quark passed through the plasma, it left behind a trailing disturbance, similar to the wake formed by an object moving through water. Instead of scattering randomly, the surrounding matter shifted and flowed in response.

This provides the clearest evidence yet that quark-gluon plasma reacts to moving particles as a true fluid. The plasma did not simply absorb the quark’s energy. It pushed back, redistributing that energy in an organized way that matches long-standing theoretical predictions.

Because the size and shape of these wakes depend on the plasma’s internal properties, the technique offers a new way to study this material.

“We’ve gained the first direct evidence that the quark indeed drags more plasma with it as it travels,” Lee said. “This will enable us to study the properties and behavior of this exotic fluid in unprecedented detail.”

Read More: A Dead Galaxy From the Early Universe Succumbed to Starvation Due to its Own Black Hole

Article Sources

Our writers at Discovermagazine.com use peer-reviewed studies and high-quality sources for our articles, and our editors review for scientific accuracy and editorial standards. Review the sources used below for this article: