What do you see when you look up at the sky? Whether you find clear blue stillness or rolling storm clouds, you’re barely catching a glimpse of the incredibly complex dynamics playing out overhead. But when viewed from above by a cutting-edge weather satellite, these dynamics reveal themselves.

The first images from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Meteosat Third Generation-Sounder 1 satellite (MTG-S1) offer a stunning view of Earth’s atmospheric chaos. This satellite, launched from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida, in July, uses a remote sensing technique called “infrared sounding” to capture data on temperature, humidity, wind, and trace gases that scientists will eventually use to generate 3D maps of the atmosphere.

The new images, taken on November 15, include both temperature and humidity maps of the atmosphere above Europe and Northern Africa. The satellite’s geostationary position above the equator allows it to maintain a fixed position relative to Earth and follow this region as the planet rotates, providing new data every 30 minutes. That MTG-S1 can capture such exquisite detail from its perch so far above our planet is impressive; geostationary satellites aren’t exactly close, working some 22,000 miles (35,400 kilometers) from Earth.

“Seeing the first Infrared Sounder images from the MTG-Sounder satellite really brings this mission and its potential to life,” Simonetta Cheli, ESA’s Director of Earth Observation Programmes, said in a statement. “We expect data from this mission to change the way we forecast severe storms over Europe.”

Mapping heat and humidity from space

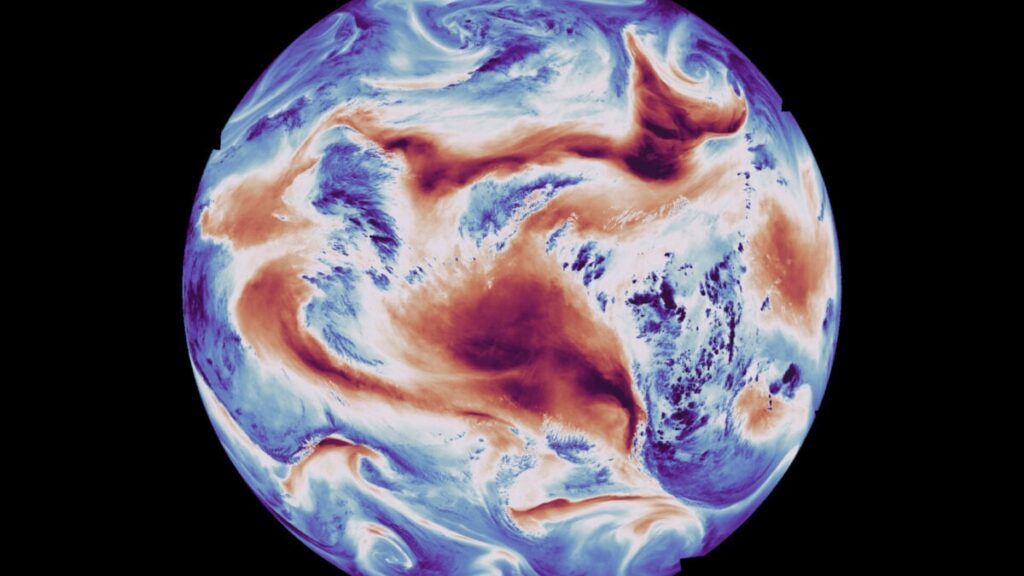

The satellite’s infrared sounder is the first instrument of its kind to operate from geostationary orbit, according to ESA. It observes the atmosphere in 1,700 narrow wavelength bands across the infrared spectrum to detect the distribution, circulation, and temperature of water vapor in the atmosphere. The instrument captured the humidity image above using its medium-wave infrared channel.

Blue areas correspond to areas of higher humidity, while red signals lower humidity. The driest regions of the atmosphere—those in dark red—are located over the Sahara Desert and the Middle East at the top of the image and over the South Atlantic Ocean at the center of the image. Dark blue, high-humidity regions are concentrated over East Africa and near the poles.

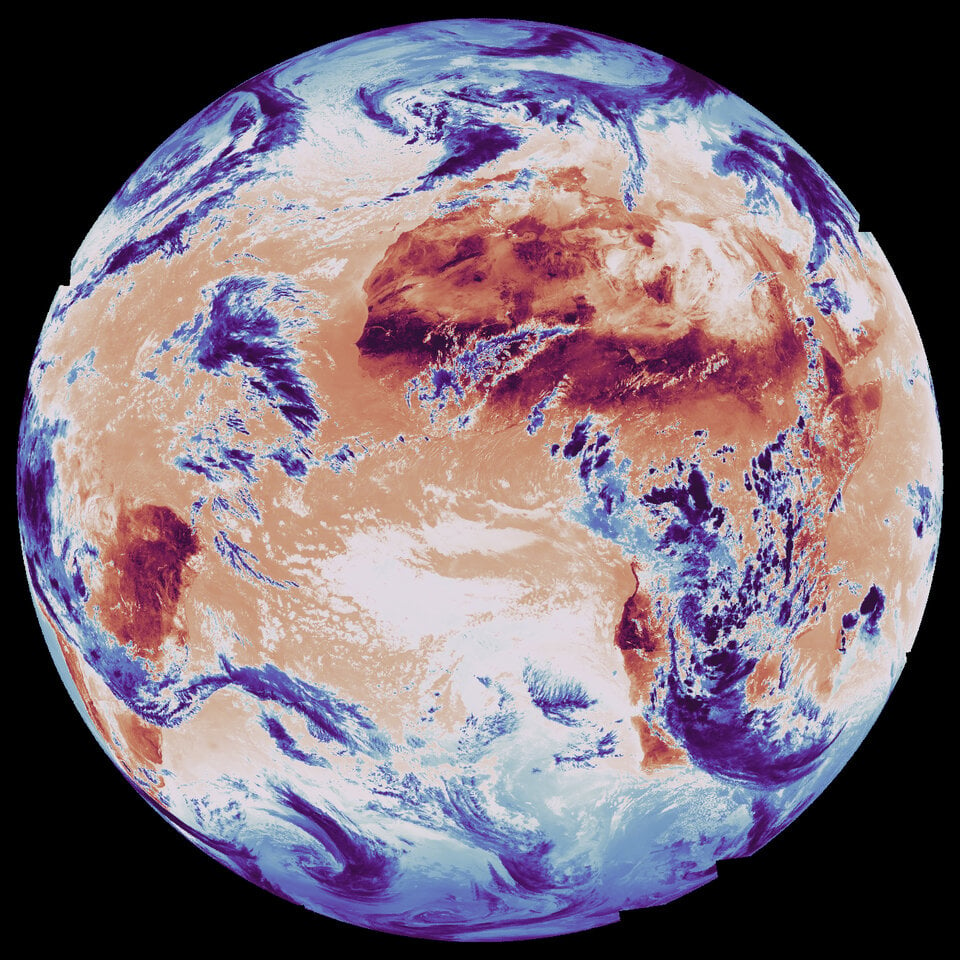

To create the temperature image below, MTG-S1 used the infrared sounder’s long-wave infrared channel. This measures temperatures at Earth’s surface and at the tops of clouds. The warmest areas, shown in dark red, mainly appear over land surfaces, while cold, dark blue areas typically correspond to clouds.

Global surface and cloud-top temperatures imaged MTG-Sounder © European Space Agency

Global surface and cloud-top temperatures imaged MTG-Sounder © European Space Agency

It will come as no surprise that the warmest (dark red) areas are located over Africa and South America—you can actually make out the coastline of western Africa in the top center of the image. In the bottom right, the western coasts of Namibia and South Africa are also shown in red beneath the curve of a cold cloud shown in blue.

A warming world requires enhanced forecasting

Improving the accuracy of real-time weather forecasting and storm tracking is critical in a rapidly changing climate. As rising global temperatures increase the frequency and intensity of major storms, satellite imagery plays a crucial role in protecting communities and infrastructure.

ESA’s MTG mission aims to significantly improve satellite-based weather forecasting and storm tracking. MTG-S1 is the second satellite launched as part of this program, which will eventually include six weather satellites. The first, Meteosat Third Generation-Imager 1 (MTG-I1), launched in 2022. It observes clouds and lightning to support early detection of and prediction of rapidly developing severe storms.

Together, these two satellites are already providing meteorologists with a more complete picture of Earth’s weather system and its ever-changing behavior. ESA officials say they will also help forecasters predict extreme weather events earlier than ever before, giving communities more time to prepare for impacts.