Scientists studied active galactic nuclei, focusing on how quasars at their centers interact with surrounding dust. They found that this interaction is closely related to the variability of radiation in the visible and infrared ranges of the spectrum.

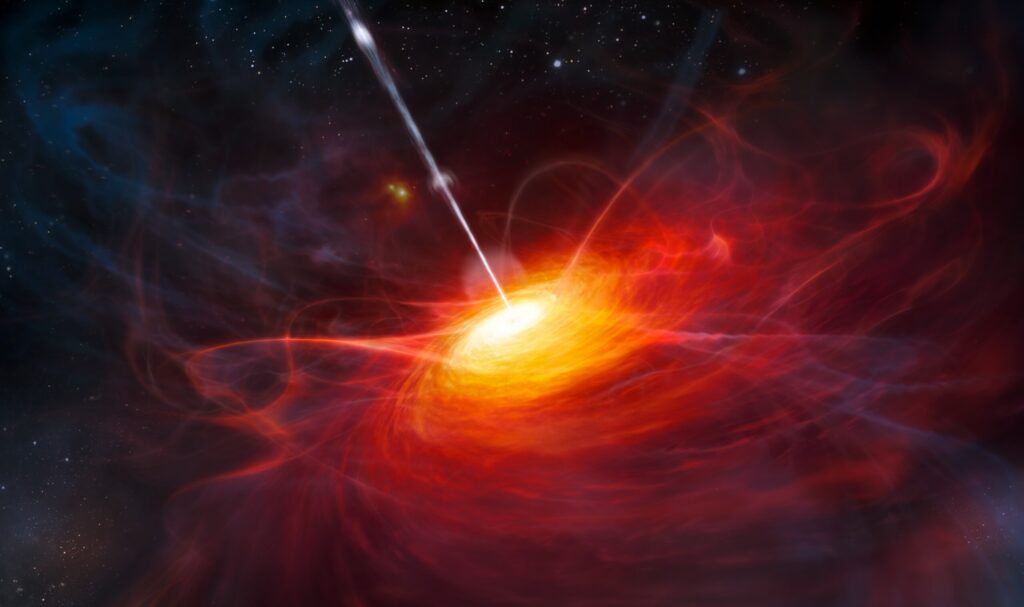

Quasar. Source: Wikipedia

Quasar. Source: Wikipedia

Active galactic nuclei

A study on the density of dust covering quasars was recently published in The Astrophysical Journal. Its authors are scientists from the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, who used the VISTA (Visible and Infrared Survey Telescope for Astronomy) telescope for their work.

Quasars are supermassive black holes that actively absorb matter from outside and “return” part of it in the form of radiation that is visible across the entire Universe. They, along with gas and dust clouds and nebulae located directly next to them, form the active nucleus of a galaxy.

Scientists have long noticed that in the near-infrared spectrum, which is currently the most popular for their research, they occasionally change brightness. It is likely that this process is related to how dust, i.e., fairly large particles, moves around them.

Dust movement

Scientists selected four quasars with the most noticeable variability for their study and began to examine them in two adjacent infrared ranges: visible and mid-infrared. Next, with three different images of the same objects, they began to construct theoretical models that would explain the differences between them.

The researchers began comparing the observed pattern with various models of dust motion around them. They concluded that in the torus surrounding the black hole, smaller particles dominate in the inner regions, while larger particles dominate in the outer regions.

It is clear that the picture is actually more complex than scientists have established. Each quasar is unique in its own way, and the sample on which the conclusions are based is small. However, the most intense processes that determine the appearance of each galaxy occur around the nucleus, and it is these processes that we know a little more about.

According to phys.org