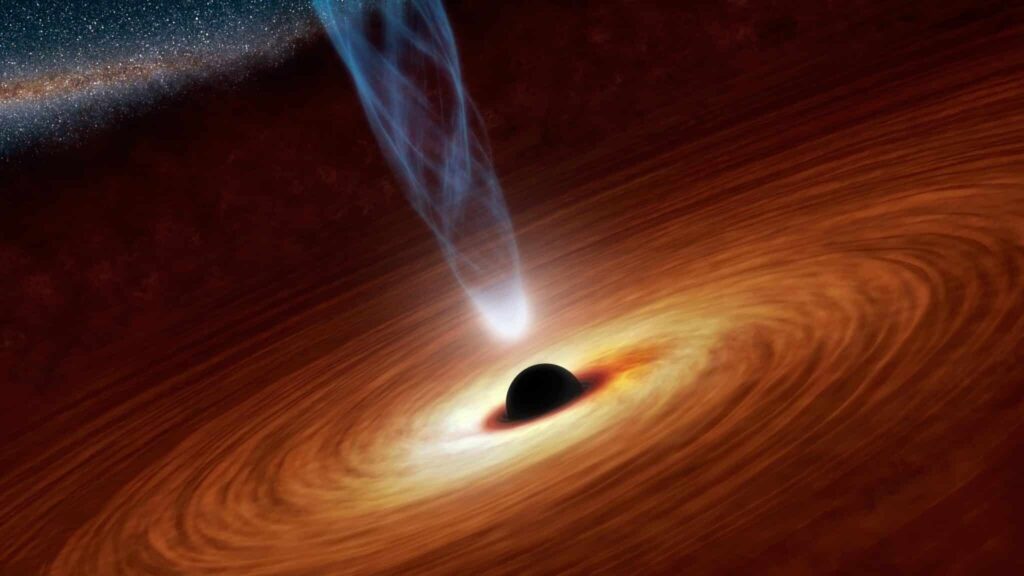

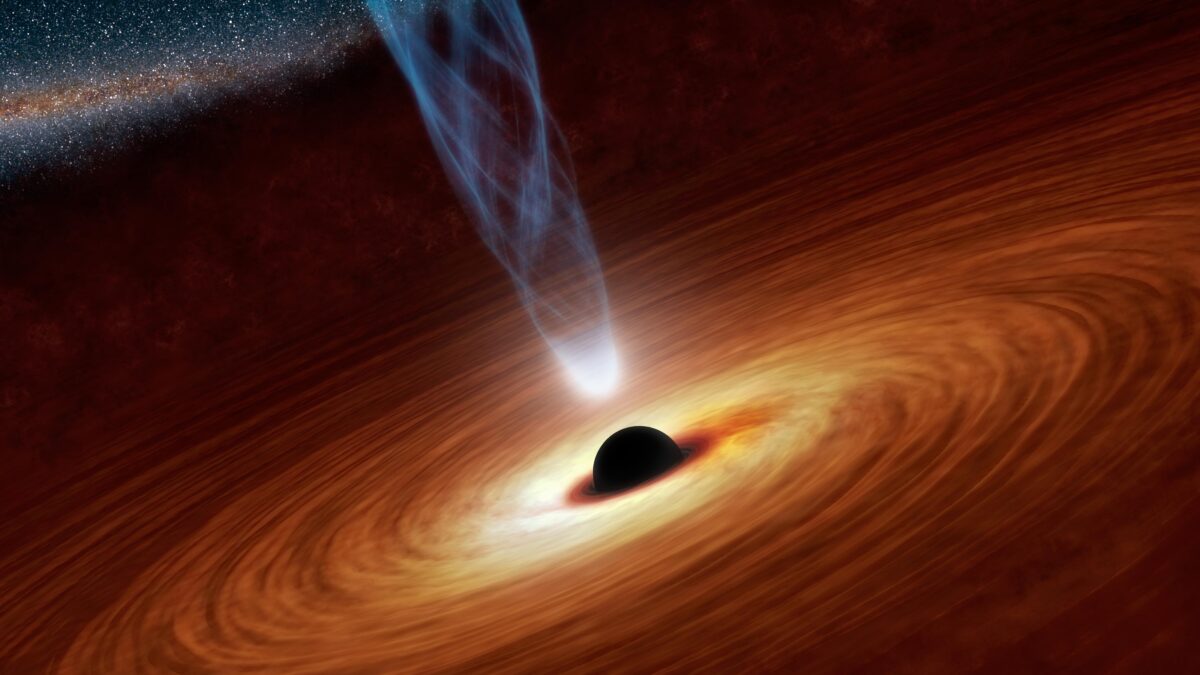

Artist’s impression of a supermassive black hole system. Infalling gas forms a bright corona near the black hole. In some systems, a jet is launched. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

In A Nutshell

A black hole in the early universe is eating 13 times faster than a classic physics rule says is possible

It’s breaking the “Eddington limit,” a rule of thumb for black hole growth, like a car going 800 mph in a 60 mph zone

The discovery could explain how black holes got so massive so quickly after the Big Bang

Scientists think they caught it during a rare “transition phase” after a feeding frenzy

Deep in the early universe, a black hole is gorging itself on matter at a rate that should be impossible.

Located 11.6 billion light-years from Earth, this cosmic glutton is feeding 13 times faster than a classic rule of physics says it should be able to. When a black hole eats too quickly, its own energy output should push away incoming material, like trying to drink from a fire hose. But this black hole, discovered by an international team using the eROSITA X-ray telescope, doesn’t seem to have gotten the memo.

To be clear, this doesn’t mean Einstein’s relativity is wrong. It means the black hole is exceeding what’s called the “Eddington limit,” a longstanding rule of thumb for how fast black holes can grow before their own radiation pushes fuel away.

The finding, published in The Astrophysical Journal, could help solve one of astronomy’s biggest questions: how did supermassive black holes get so enormous so quickly after the Big Bang?

A Massive Mystery

This black hole is shining so brightly that it’s either truly gigantic (one of the most massive objects ever discovered) or it’s breaking the rules about how fast black holes can eat.

When astronomers calculated how much matter the black hole would need to consume to shine this bright, the numbers didn’t make sense. Even using their most generous estimates, it’s eating far faster than should be physically possible. The X-ray measurements made things even stranger, suggesting it’s feeding at 13 times the theoretical limit.

Most black holes that eat this fast should be dim in X-rays because they create a thick, puffy disk that blocks the high-energy light. This one is not dim.

Time Traveler’s Snapshot

Scientists think they’ve caught this black hole at a very specific moment in time: right after a massive meal.

A few years ago, astronomers watched a nearby black hole called 1ES 1927+654 go through something similar. A star likely got too close and was ripped apart by gravity. The black hole gobbled up the debris, and weird things happened: First, its X-ray glow dimmed as it gorged itself. Then, as things settled down, the X-rays came roaring back even brighter than before.

This distant black hole looks like it’s in that peak X-ray phase. The hot region above the black hole that produces X-rays may have reheated as the feeding frenzy wound down.

There is, however, a catch. While the nearby black hole’s transition took three years, this one’s transformation would play out over 300 years in its own time frame. From Earth, thanks to the way the expanding universe stretches time, we’d need to watch for 1,300 years to see the full show.

Artist’s impression of a supermassive black hole system. Infalling gas forms a bright corona near the black hole. In some systems, a jet is launched. (Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The Quasar That Shouldn’t Exist

Scientists have two theories about these observations. First, the black hole’s powerful radio jet might be boosting some light particles up to X-ray energies, adding extra brightness. Second, the hot region above the black hole might be unusually warm for something eating this fast, perhaps because it recently reheated after cooling down during peak feeding.

Jet Engine at the Edge of Physics

Here’s what makes this discovery even stranger: While speed-eating at impossible rates, this black hole is also firing off a powerful jet of energy.

Radio telescope observations show the jet is young and compact, not yet stretched across hundreds of thousands of light-years like older jets. It may have only recently switched on. And it’s carrying enough power to reshape its entire host galaxy: heating gas, pushing it away, and potentially shutting down star formation.

That’s important because scientists thought jets mainly appeared when black holes were eating slowly, not quickly. If black holes in the early universe could produce powerful jets while also growing rapidly, it means they had two ways to influence their surroundings at once: through their own growth and through their ability to regulate star formation in their galaxies.

The finding suggests this galaxy-shaping feedback was already happening less than 2 billion years after the Big Bang.

How did supermassive black holes become so big so quickly? (Credit: The universe 001 on Shutterstock)

Ancient Giant’s Growing Pains

This black hole was spotted by the eROSITA X-ray telescope, which scanned a huge swath of sky and found more than 17,000 X-ray sources. This one stood out immediately. It’s what astronomers call a quasar, which is essentially a black hole so active and bright that it outshines its entire home galaxy.

As mentioned earlier, this discovery tugs at a longstanding mystery: How did supermassive black holes get so big so fast? If they grew by steady, slow feeding, even black holes formed from the first stars would struggle to reach their enormous sizes this early in cosmic history.

Super-fast feeding episodes offer an answer. If black holes regularly experience growth spurts where they break the speed limit, they could balloon in size much faster than anyone thought. The catch is that these feeding frenzies probably happen in dusty, gas-rich environments that hide the black holes from optical telescopes, meaning we’ve been missing a lot of them.

The research team thinks objects like this one might make up more than half of the brightest black holes at these distances, far more than the 10% we typically see closer to home.

“This discovery may bring us closer to understanding how supermassive black holes formed so quickly in the early universe,” says lead author Sakiko Obuchi, from Waseda University, in a statement. “We want to investigate what powers the unusually strong X-ray and radio emissions, and whether similar objects have been hiding in survey data.”

Future observations with the James Webb Space Telescope could reveal whether this black hole’s dusty surroundings still show signs of that earlier feast. For now, it indicates that the early universe was wilder than our equations predicted.

Paper Summary

Limitations

The study acknowledges several limitations in its analysis. The X-ray spectral fit is based on relatively low photon counts (121 net counts), which increases uncertainty in the measured photon index and absorption estimates. The single-epoch black hole mass estimate carries typical uncertainties of 0.3-0.4 dex and may be biased for sources with strong outflows. The jet power calculation relies on empirical relationships that have significant scatter and may not apply equally well at high redshifts. The proposed transitional phase interpretation is based on analogy with a single nearby source (1ES 1927+654) and would benefit from additional examples and longer-term monitoring. The study is also limited to sources with spectroscopic redshifts, which represent only ~32% of sources at ID830’s brightness, potentially introducing selection biases in the estimated number density of similar objects.

Funding and Disclosures

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI grants 25K01043 (K.I.), 23K13154 (S.Y.), and 22H00157 (K.H.). K.I. also received support from the JST FOREST Program grant JPMJFR2466 and the Inamori Research Grants. Z.I. acknowledges support from the Excellence Cluster ORIGINS, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy (EXC-2094 – 390783311).

Publication Details

Obuchi, S., Ichikawa, K., Yamada, S., Kawakatu, N., Liu, T., Matsumoto, N., Merloni, A., Takahashi, K., Zaw, I., Chen, X., Hada, K., Igo, Z., Suh, H., & Wolf, J. (2026). “Discovery of an X-Ray Luminous Radio-loud Quasar at z = 3.4: A Possible Transitional Super-Eddington Phase.” The Astrophysical Journal, 997:156. DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae1d6d. The authors are affiliated with institutions including Waseda University (Japan), Tohoku University (Japan), National Institute of Technology Kure College (Japan), University of Science and Technology of China, Max-Planck-Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik (Germany), New York University Abu Dhabi (UAE), Nagoya City University (Japan), National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Exzellenzcluster ORIGINS (Germany), International Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab (USA), and Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie (Germany).