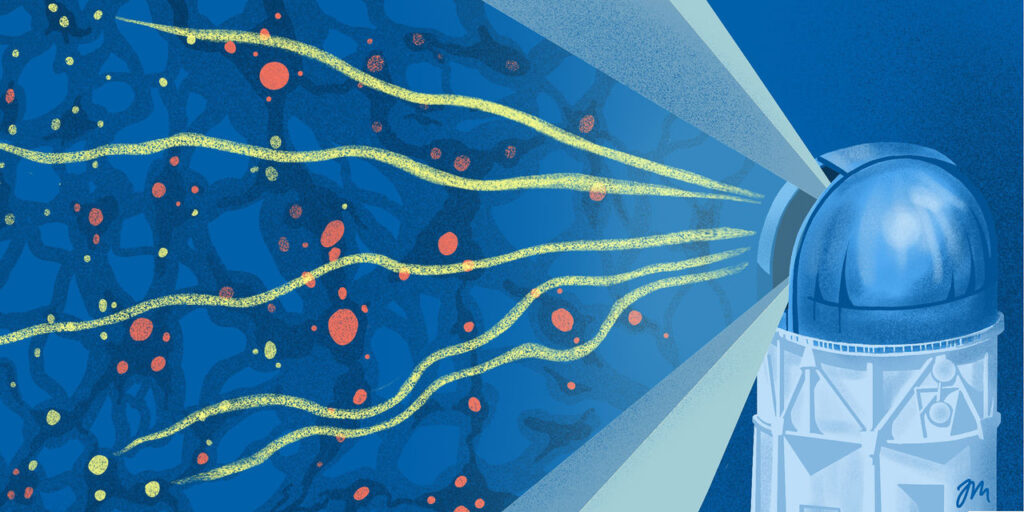

Images captured in Chile demonstrate how light from distant galaxies is distorted by gravitational forces. And this effect is intensified in regions featuring clusters of galaxies.

“If light travels in a straight line, we see a clear image. But if light is deflected by gravity, the image looks warped,” she said.

Muir is contributing to the project as part of the analysis team where she led the development of statistical techniques for checking the consistency of different parts of the data. They validated theoretical predictions that are compared measurements and the process of using those comparisons to learn about the physics of dark energy.

She has a background in applied mathematics, earning a master’s degree from Cambridge University before she received a doctoral degree in physics. Muir contributed to the data analysis using UC’s Advanced Research Computing Center.

“I wanted to get into theory, but as a doctoral student I realized the things I found most compelling were at the interface of theory and experiment,” Muir said. “We use statistics to test our understanding of the universe.”

She also had an opportunity to visit Chile where she took part in two shifts as an observer on the project in 2017 and 2018.

Physicists are still grappling with concepts outlined by Albert Einstein in his theory of general relativity.

“The simplest model for dark energy is the cosmological constant. Is dark energy constant with time or is it enhanced or diluted as the universe expands?” Muir said.

“I’m excited to be part of these big collaborative efforts to use data to say something about that,” she said.

“In physics we want to understand what things are made of and what mathematical laws govern how they behave,” she said. “And we still can’t explain 95% of the universe.”

Featured image at top: Researchers are studying the way galaxies cluster to learn more about a force called dark energy that explains why the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate. Illustration/Jessica Muir