The European Space Agency’s (ESA) Solar Orbiter has discovered that solar flares act like avalanches, triggered by weak disturbances that grow into powerful plasma rains that continue even after the flare ends.

An international team of researchers discovered magnetic avalanches in data collected during Solar Orbiter’s September 2024 approach to the Sun, which provided an important new view of solar flares. The team reports their findings in a recent paper published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, providing a detailed new understanding of solar flares that pose a hazard to satellites, astronauts, and even ground-based electrical infrastructure.

Solar Flares

Energy released from tangled magnetic fields produces solar flares, as the twisted lines of these fields break and reconnect. When those reconnections occur, they can rapidly heat up and push out million-degree plasma in the form of a solar flare. Driven by solar winds, these flares reach Earth, potentially wreaking havoc on our communications infrastructure.

First, solar flares can impact Earth’s many artificial satellites, responsible for the communication and GPS systems that bring together our modern connected world. As flares get closer to the surface, they can take out electrical and wired communications infrastructure. As such, these solar events pose a major threat to human civilization, and scientists must carefully monitor and understand them.

Unfortunately, many specifics about how these flares release so much energy so quickly remain unclear. These later 2024 observations provided important new data to change that, as four separate instruments aboard the Solar Orbiter provided the clearest observation of a solar flare ever recorded.

Solar Orbiter Observations

With its Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI), the Solar Orbiter resolved features in the Sun’s corona only a few hundred kilometers wide, with observations every two seconds. Piercing the solar atmosphere, the SPICE, STIX, and PHI instruments allowed the team to collect temperature and depth data all the way down to the Sun’s surface. This enabled the researchers to observe events percolate for 40 minutes before a solar flare finally erupted.

“We were really very lucky to witness the precursor events of this large flare in such beautiful detail,” said lead author Pradeep Chitta of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Göttingen, Germany. “Such detailed high-cadence observations of a flare are not possible all the time because of the limited observational windows and because data like these take up so much memory space on the spacecraft’s onboard computer. We really were in the right place at the right time to catch the fine details of this flare.”

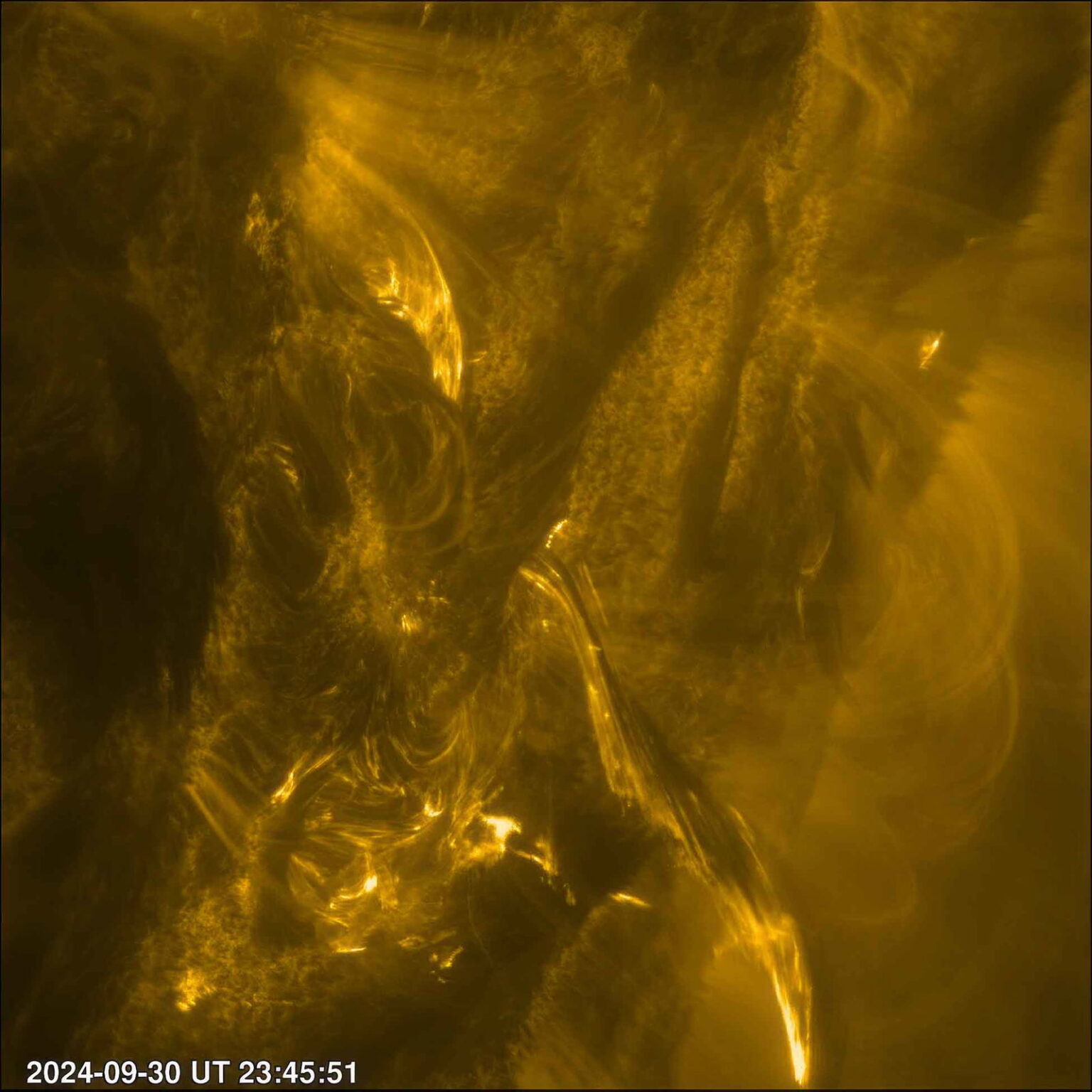

As EUI began its observations, a dark arch of twisted magnetic fields and plasma connected to a cross-shaped structure of brightening magnetic field lines was already visible. Every image frame, captured at two-second intervals, displayed new magnetic field strands, twisted like ropes. Eventually, the region destabilizes as strands break and reconnect, producing energy outflows that appear as bright spots in the images, forming a magnetic avalanche.

“These minutes before the flare are extremely important and Solar Orbiter gave us a window right into the foot of the flare where this avalanche process began,” explained Pradeep. “We were surprised by how the large flare is driven by a series of smaller reconnection events that spread rapidly in space and time.”

Solar Flare Avalanches

The avalanches we experience on Earth have already been considered a possible model for describing large-scale solar storms, but this is the first time researchers have collected enough precise data to determine that the model applies to individual solar flares as well.

SPICE and STIX had both been observing slowly rising emission from ultraviolet to X-rays in the region, culminating in a dramatic X-ray emission spike during the flare. When reconnection speeds increased, particles accelerated to almost half the speed of light. Those observations also revealed that during the events, energy moved from the magnetic field to the surrounding plasma.

“We saw ribbon-like features moving extremely quickly down through the Sun’s atmosphere, even before the main episode of the flare,” said Pradeep. “These streams of ‘raining plasma blobs’ are signatures of energy deposition, which get stronger and stronger as the flare progresses. Even after the flare subsides, the rain continues for some time. It’s the first time we see this at this level of spatial and temporal detail in the solar corona.”

Understanding Space Weather

Activity quieted down immediately after the flare, and STIC and SPICE observed the plasma cool as particle emissions returned to normal levels. PHI completed the 3D view by tracking the flare’s imprint on the Sun’s surface.

“We didn’t expect that the avalanche process could lead to such high-energy particles,” explained Pradeep. “We still have a lot to explore in this process, but that would need even higher resolution X-ray imagery from future missions to really disentangle.”

“This is one of the most exciting results from Solar Orbiter so far,” commented Miho Janvier, ESA’s Solar Orbiter co-Project Scientist. “Solar Orbiter’s observations unveil the central engine of a flare and emphasise the crucial role of an avalanche-like magnetic energy release mechanism at work. An interesting prospect is whether this mechanism happens in all flares, and on other flaring stars.”

Armed with this new understanding of the cascading eruptions associated with solar flares, researchers may now be able to refine solar flare prediction techniques even further in the years ahead.

The paper, “A Magnetic Avalanche as the Central Engine Powering a Solar Flare,” appeared in Astronomy and Astrophysics on January 14, 2025.

Ryan Whalen covers science and technology for The Debrief. He holds an MA in History and a Master of Library and Information Science with a certificate in Data Science. He can be contacted at ryan@thedebrief.org, and follow him on Twitter @mdntwvlf.