Whew. Is your head hurting yet? Don’t worry. The main point for scientists is that these superficial connections between black holes and the universe don’t necessarily imply that one is the other. In order to take that leap, physicists would need to know what observable results such an idea might have.

“We have theories and they have consequences,” says Alex Lupsasca, a physicist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. “If the implications of the theory are ruled out by an experiment, then we could say the assumptions are inconsistent or wrong.”

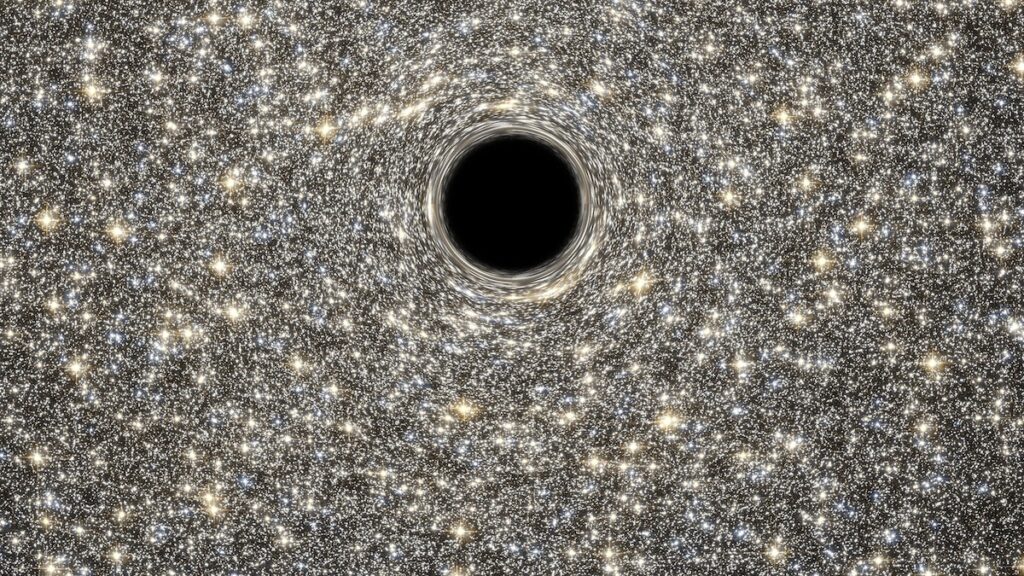

How to tell if your universe is in a black hole

So what would be the observable consequences if our universe was, in fact, inside of a black hole? For one, there would be a kind of natural direction or orientation to the cosmos—galaxies spinning in a favored direction or a subtle axis in the leftover heat from the big bang that fills the universe. “You would expect some sort of gradient across our universe,” says Afshordi. “One direction would be towards the center of the black hole, another towards the outside of the black hole.”

Yet our best measurements show that, at the largest scales, the cosmos appears to be quite repetitive. Physicists refer to this as the cosmological principle. It states that the universe has no special direction, and it’s the same pretty much everywhere. How such uniformity could arise from the birth of a black hole is a challenge for anyone claiming the cosmos is inside of one. Black holes are born from dying stars—a process that’s messy, chaotic, and far from uniform.

There is also the problem of the black hole’s singularity. That infinitesimal point is a fated final moment for anyone or anything that falls inside a black hole, kind of the opposite of a rapidly expanding cosmos.